NEXT STORY

Setting up a physiology department at Glasgow Veterinary College

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Setting up a physiology department at Glasgow Veterinary College

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. My journey from a mining community to a scholarship at St Andrews | 3 | 701 | 06:00 |

| 2. Highlights of the St Andrews and Dundee Medical Schools | 304 | 04:10 | |

| 3. A year in the physiology department at St Andrews | 1 | 256 | 02:57 |

| 4. Working in Singapore | 280 | 04:01 | |

| 5. Setting up a physiology department at Glasgow Veterinary College | 212 | 02:42 | |

| 6. Developing the idea of a beta receptor antagonist | 2 | 413 | 06:53 |

| 7. Working in the dream world of Imperial Chemical Industries | 298 | 03:41 | |

| 8. The accident that led to beta blockers | 3 | 976 | 05:31 |

| 9. The cautionary tale of James Raventos | 1 | 299 | 01:28 |

| 10. Simulating fear in patients | 253 | 04:14 |

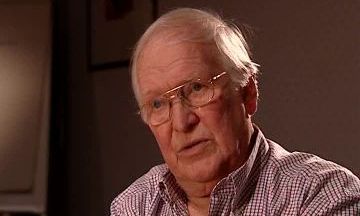

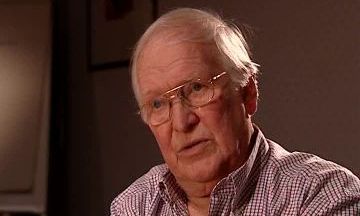

After a year I applied... in fact, it's the only job I've ever applied for and I didn't get it. So I... I applied to go to Makerere College, and the reason I wanted to go abroad was because my residential scholarship was for four years and so for my last year I had to borrow money. And so here I was on a pittance of a salary and big debts, and just got married, and I knew I couldn't live with this so I had to emigrate, and so I tried to go to Uganda, failed, but they offered me a job in Singapore, so that's where I went. So for three years I was in Singapore earning enough money to pay off my debts. And, incidentally, this is one reason why I'm so passionately against young people being saddled with debt, as they are today, at the start of their careers. I think it's just abominable. Anyway, a bit of politics. In Singapore I learned to teach more. It's quite interesting, you start off... it's a polyglot community; mainly Chinese, but there are Indians of various types, and there's Malays of course. And, you start off and everybody is vaguely browner than you are, and then you gradually learn to recognise the Chinese and the Tamils and the Sikhs and Malays and so on, and you're aware of the differences. And then, after about a year, you don't notice them anymore, or you notice all the ones you like and the ones you don't like, so you become sort of colour blind, which I found an interesting experience, in retrospect. And, incidentally, I was teaching these youngsters, medical students, and I was trying to teach them human physiology by making them do experiments on themselves. Now, you were talking a moment ago about passing a nasogastric tube to...so one of the experiments I did was to get the students to pass a tube on each other or on themselves so that they could sample the gastric secretion and so on, and it was fascinating. The Chinese could just... no problems. All the others – the Indians, the Malays: they gagged and choked. It was a clear difference between them. I did research and I lost my way. I became so obsessed with trying... what I was trying to do was measure, or find out, whether viscosity changes in the blood depending on whether the gut was absorbing water – fluid – or secreting, and so I thought I could detect this if I measured pressure flow relations. And so I got absorbed in all the engineering and the maths, and I completely and utterly... the whole thing was far away beyond my skill or capacity. So what I did learn there was not how to do research but how not to do it, and I learned, I think, the most important lesson of my life which is: in research it is impossible to make an experiment too simple and that, really, what you have to do is take a problem and see if you can break it down to smaller problems. And, if you get a problem, you know this... that... that's almost moronically simple, it seems hardly worth asking, the only thing you don't know is the answer, but you know it's a question which is answerable, and then you've got yourself an experiment.

The late Scottish pharmacologist Sir James W Black (1924-2010) revolutionised medical treatment of hypertension and angina with his invention of propranolol, the first ever beta blocker. This and his synthesis of cimetidine, used for the treatment of peptic ulcers, earned him the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1988.

Title: Working in Singapore

Listeners: William Duncan

After graduating with a BSc Bill Duncan went on to gain a PhD from Edinburgh University in 1956. He joined the Pharmaceuticals Division of ICI where he contributed to the development of a number of drugs. In 1958, he started a collaboration with Jim Black working on beta blockers and left ICI with him in 1963 to join the Research Institute of Smith Kline & French as Head of Biochemistry. He collaborated closely with Black on the H2 antagonist programme and this work continued when, in 1968, Duncan was appointed the Director of the Research Institute. In 1979, he moved back to ICI as Deputy Chairman (Technical), a post he occupied until 1986 when he became Chairman and CEO of Coopers Animal Health. He ‘retired’ in 1989 but his retirement was short-lived and he held a number of directorships in venture capital backed companies. One of his part-time activities was membership of the Bioscience Advisory Board of Johnson and Johnson who asked him to become Chairman of the Pharmaceutical Research Institute of Johnson and Johnson in New Jersey. For personal reasons he returned to the UK in 1999, but was retained by Johnson and Johnson until 2006 in a number of senior position in R&D working from the UK. From 1999 to 2007 he was a non-executive director of the James Black Foundation. He is now fully retired.

Tags: Singapore, Makerere College, Uganda

Duration: 4 minutes, 1 second

Date story recorded: August 2006

Date story went live: 02 June 2008