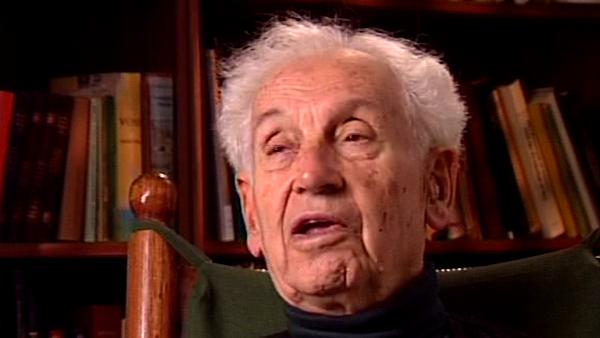

I was, I believe, the first one who very… in great detail and with great emphasis pointed out that something like the biological populations in which every individual is different from every other one, something that is implicit in Darwin's theory of natural selection, that such a thing does not exist in the inanimate world. And the… any… or the… the developing philosophy of biology, in that philosophy the concept of populations, as I have just described, has become very prominent. It's one of the cornerstones of a philosophy of biology. Another one, of course, is the fact that in inanimate nature all activities that occur are due to the action of the universal laws of physics, while in biology we have a dualism of effects. Any activity of a living organism, whether it is in physiology or in growth or in behaviour, always is controlled by two sets of factors: the first one being these same universal laws of physics, but the second one being the genetic programme which details… which controls, to a greater or lesser extent, every single action and activity of a living organism. So, here we have already two great distinctions of organisms as compared to inanimate matter. Now, I have in one of my recent publications… several of my recent publications, a long listing of all the differences between living matter… living organisms I should better say, and inanimate matter. And I cannot, now, off the top of my head give you this list again. But, for instance, one of the great distinctions is that history is an important component of any living phenomenon because history through evolution, through natural selection, has affected the genotype of every organism. While in… in the physics, for instance, whether an electron that we find here on earth has come from Mars originally or was in a… in a high weight metal or in a… in hydrogen or helium, all this sort of thing is completely irrelevant; an electron doesn't have a history the way an organism does.