NEXT STORY

MIT or suicide

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

MIT or suicide

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11. Henry Margenau's physics class | 3353 | 05:03 | |

| 12. The eccentric Gregory Breit | 2598 | 02:38 | |

| 13. How World War II affected the graduate program at Yale | 1926 | 01:27 | |

| 14. The unwritten letter of thanks | 2024 | 02:22 | |

| 15. The many varied courses at Yale | 2014 | 03:06 | |

| 16. Applying to graduate schools | 1 | 2214 | 04:55 |

| 17. MIT or suicide | 3315 | 02:49 | |

| 18. Making friends at MIT | 2546 | 01:40 | |

| 19. Interaction with other MIT students | 2199 | 01:00 | |

| 20. Parity conservation: an inviolable principle? | 1 | 2340 | 02:31 |

I was impressed with the Ivy League, and so my preference was for some graduate school in the Ivy League. Princeton was supposed to be a wonderful place for theoretical physics, and Harvard was supposed to be very good, so those were the two places I wanted to go. I would have considered also staying at Yale, although I knew that Harvard and Princeton were probably better for modern theoretical physics. I talked with Ernie Pollard, the nuclear physicist on the faculty, who was a Fellow of my college and, I think, a graduate of Cambridge, and he suggested Michigan as a good place. So I thought of applying to Michigan; I'm not sure if I actually got around to filling out the application, but I did, I know I did apply to Harvard and Princeton, and Yale. But there was a problem. I had signed up for a senior essay with Henry Margenau, but he assigned me a problem in ambipolar diffusion and I understood nothing about how to tackle such a problem, how to make approximations, how to consider data, experimental data in making suitable approximations. Going back and talking with him about suggestions and so on, I had some fantastic idea that what I should do is take the equations and somehow solve them, which was absurd. I had no understanding of what a theoretical physicist would do in such a case. If I had had some understanding, I probably could have done something, or might have been able to do something useful, but I had no idea what the context was for working on such a thing, so I actually didn't do anything. And I think that affected my record very seriously, even though my course grades were very high and I was… I would have been first in my class in science if I had graduated in ’47. In the last year I took a number of very large classes, graded... where the examinations and essays were graded by graduate students and so on, and the marks just didn't get very high in those subjects. So my average went down and I… I paid no attention to things like that, but what happened was my average went down and so I was second in science when I actually graduated in ‘48...

[Q] Who...

...but the problem, I think, was the essay, which I hadn't done. Pardon?

[Q] Who was first?

A mathematician. And so actually these applications were in many cases not so successful. Princeton, I was rejected. Harvard, I was accepted but they didn't offer me a scholarship or, I might have gotten an assistantship but they didn't suggest it, they… I presumably would have had to do something myself to get one and I was discouraged. Later on people told me I was refused at Harvard, but that wasn't true, I got a letter… I did get a letter of acceptance from Harvard but no further encouragement to deal with the financial problems. At Yale I was accepted in mathematics although I had applied in physics. The mathematicians loved me, and...

[Q] I mean… without epsilons and deltas?

Well, I'd taken a lot of graduate courses in mathematics and they – the mathematics professors – liked me and they thought I would… would be good in mathematics. I don't know if I would have been good in mathematics or not. The motivation might have been lacking to work on that pure mathematics, but… but anyway they liked me, they admitted me to graduate school, but the physicists didn't. The physics department at Yale didn't admit me to graduate school, presumably because of this essay matter, at least, that's what I assume. I've never seen the documents. Years later I gave a lecture at Princeton University and I happened to mention on my visit that I hadn't been admitted to graduate school at Princeton. And Arthur Whiteman and Eugene Wigner went over to the Graduate College to look at the records, but my records had disappeared. So we never found out what the problem… we never found out what the problem was.

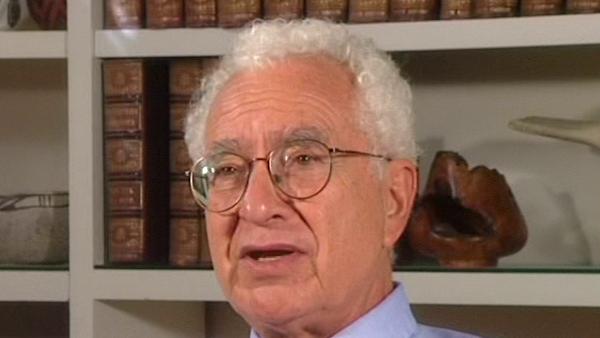

New York-born physicist Murray Gell-Mann (1929-2019) was known for his creation of the eightfold way, an ordering system for subatomic particles, comparable to the periodic table. His discovery of the omega-minus particle filled a gap in the system, brought the theory wide acceptance and led to Gell-Mann's winning the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1969.

Title: Applying to graduate schools

Listeners: Geoffrey West

Geoffrey West is a Staff Member, Fellow, and Program Manager for High Energy Physics at Los Alamos National Laboratory. He is also a member of The Santa Fe Institute. He is a native of England and was educated at Cambridge University (B.A. 1961). He received his Ph.D. from Stanford University in 1966 followed by post-doctoral appointments at Cornell and Harvard Universities. He returned to Stanford as a faculty member in 1970. He left to build and lead the Theoretical High Energy Physics Group at Los Alamos. He has numerous scientific publications including the editing of three books. His primary interest has been in fundamental questions in Physics, especially those concerning the elementary particles and their interactions. His long-term fascination in general scaling phenomena grew out of his work on scaling in quantum chromodynamics and the unification of all forces of nature. In 1996 this evolved into the highly productive collaboration with James Brown and Brian Enquist on the origin of allometric scaling laws in biology and the development of realistic quantitative models that analyse the influence of size on the structural and functional design of organisms.

Tags: Ivy League, Princeton University, Harvard University, Yale University, University of Michigan, Ernie Pollard, Henry Margenau, Arthur Whiteman, Eugene Wigner

Duration: 4 minutes, 55 seconds

Date story recorded: October 1997

Date story went live: 24 January 2008