NEXT STORY

Helping younger craftsmen to exhibit

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Helping younger craftsmen to exhibit

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 51. Making the Millennium watches with Roger Smith | 2470 | 03:23 | |

| 52. Clear evidence that I made a contribution to horology | 1619 | 00:54 | |

| 53. My book on The Art of Breguet | 1772 | 03:48 | |

| 54. Watches written with Sam Clutton | 1471 | 04:02 | |

| 55. My second book: English & American Watches | 1159 | 01:01 | |

| 56. Writing The Practical Watch Escapement | 1385 | 02:07 | |

| 57. Watchmaking explained how to make escapements | 1506 | 01:20 | |

| 58. Master of the Clockmakers' Company | 1181 | 05:07 | |

| 59. Helping younger craftsmen to exhibit | 1025 | 02:15 | |

| 60. The 350th anniversary of the Clockmakers' Company | 982 | 01:48 |

I mentioned earlier the Clockmakers' Company... livery company... and it was founded in 1631, like all of these companies, as guilds to protect their industries, and you couldn't practice your art in London unless you had completed an apprenticeship, then you could enroll as a freeman. 'Free' meaning you've done your apprenticeship and you are a free man now to move about. And the Clockmakers' Company, as I say, was founded in 1631 and I was made a liveryman in about 1970ish, '68, '70 thereabouts. And I took a close interest in it because they had a marvelous collection, which I have mentioned earlier and which I did a lot of restoration work, which was very beneficial to me.

But then, to my surprise one day, I was elected to the court. The court is an inner circle of about 20 men... I nearly said distinguished people, but I felt under the circumstances I'd better leave that out. As a member of the court, of course, I could chinwag and help to pontificate with all the others, which I never did, I found it best to shut up and listen, and then have one's influence on more practical grounds that if I helped look after the collection to keep it wound and looked after and going. And I carried on like that for some years, and then in the natural sequence of events, I was elected an assistant on the court and went on to become junior warden... there are three wardens, renter warden who looks after the money, and the senior warden, who is next in line for the master's chair. And in due course I got then... I was made a master of the Clockmakers' Company, which I am very pleased about because we had 400 liverymen and only one is elected each year to the master, so I am very pleased about that. And furthermore, I was the only master who was a practicing watchmaker. So, that pleased the remainder of the court and I came to the end of my year in 1981.

And during my term as master, I had taken it upon myself to make a speech in Guildhall in London to the effect that we needed to take a greater interest in our trade and to expand it. And the reason was that Harold Wilson, who was then prime minister, had been pontificating about getting rid of the City, this wretched wealthy waste of time and self-seeking pot bellied financiers, you know, all this rubbish came tumbling out. But I realised that, you know, there was a section of the public who could fall for that kind of bait, and if he did injure the City, we'd lose our biggest earners. I mean the City earns billions and helps keep us all going. I know a lot of the people in the City spend it all on Porsche motorcars and that sort of thing, but still, it's trade and it's money and it circulates. And so I was very anxious that they shouldn't get away with this philosophy, and so I made a speech to the effect that we must improve our standing in the trade and make a contribution so that when the new master took in... in '81, he then asked me if I would form a committee... education committee, to form this apprenticeship scheme, which I did. And I ran it for 15 years, thereabouts, and it was very successful and I got lots of apprentices through and I got all the money from the National Benevolent Society, because I knew the chairman. And they had income, which they didn't need because they could only spend their income on old age pensioners and they didn't have enough old age pensioners. So I was getting about £45,000 a year from them to educate my boys, and that all worked like a charm until eventually the chairman was deposed and another chairman put in, who didn't agree with apprenticeships. We ought to give more money to our members, he says, although they don't need it, we've got to give them more money. So that brought that scheme to an end.

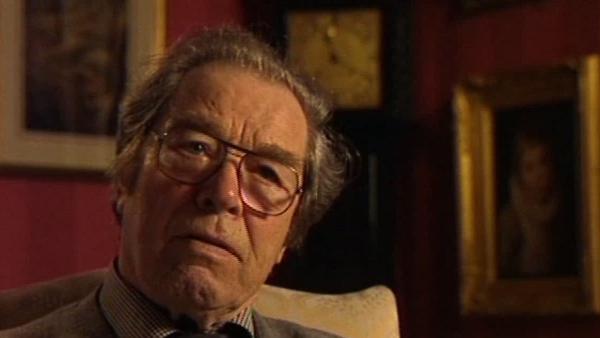

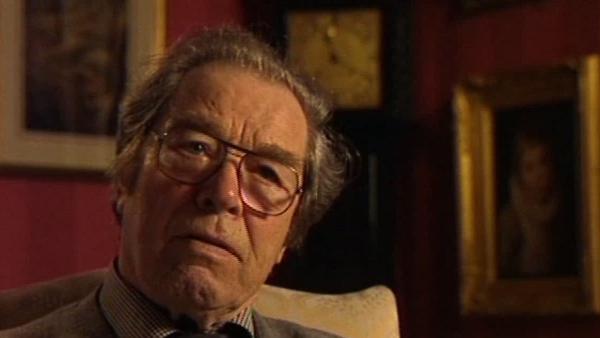

George Daniels, CBE, DSc, FBHI, FSA (19 August 1926 - 21 October 2011) was an English watchmaker most famous for creating the co-axial escapement. Daniels was one of the few modern watchmakers who could create a complete watch by hand, including the case and dial. He was a former Master of the Clockmakers' Company of London and had been awarded their Gold Medal, a rare honour, as well as the Gold Medal of the British Horological Institute, the Gold Medal of the City of London and the Kullberg Medal of the Stockholm Watchmakers’ Guild.

Title: Master of the Clockmakers' Company

Listeners: Roger Smith

Roger Smith was born in 1970 in Bolton, Lancashire. He began training as a watchmaker at the age of 16 at the Manchester School of Horology and in 1989 won the British Horological Institute Bronze Medal. His first hand made watch, made between 1991 and 1998, was inspired by George Daniels' book "Watchmaking" and was created while Smith was working as a self-employed watch repairer and maker. His second was made after he had shown Dr Daniels the first, and in 1998 Daniels invited him to work with him on the creation of the 'Millennium Watches', a series of hand made wrist watches using the Daniels co-axial escapement produced by Omega. Roger Smith now lives and works on the Isle of Man, and is considered the finest watchmaker of his generation.

Tags: The Worshipful Company of Clockmakers, Guildhall, The National Benevolent Society of Watch and Clock Makers, liveryman, James Harold Wilson

Duration: 5 minutes, 8 seconds

Date story recorded: May 2003

Date story went live: 24 January 2008