NEXT STORY

The tragic dress rehearsal of The Devils

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

The tragic dress rehearsal of The Devils

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 201. The music for The Devils | 36 | 02:08 | |

| 202. Controversy over Stavrogin's Confession | 54 | 04:43 | |

| 203. The tragic dress rehearsal of The Devils | 36 | 05:04 | |

| 204. The first performance of The Devils | 35 | 01:52 | |

| 205. Teatr Stary in Kraków | 38 | 04:25 | |

| 206. November Night | 29 | 03:52 | |

| 207. Other theatre plays | 27 | 01:51 | |

| 208. Krystyna Zachwatowicz - wife and set designer | 34 | 00:35 | |

| 209. Hamlet performed in Wawel Castle | 47 | 01:38 | |

| 210. Antigone during martial law | 66 | 02:53 |

Z tymi wszystkimi trudnościami adaptacji, która tworzyła się w trakcie prób, doszliśmy do... zbliżyliśmy się do premiery. No ale... I tutaj czekały nas same zaskoczenia. Tuż przed premierą okazało się, że aktor, który gra kapitana Lebiadkina, postać taka szemrana, pijaczka, nagle przestał przychodzić na próby, bo podobno gdzieś właśnie zaginął. Więc myślę sobie: no to już za daleko się cała sprawa posuwa, jeżeli aktorzy do tego stopnia się łączą, że tak powiem, z postaciami. Wielkie kłopoty, wielkie konflikty – tu Wojciech Pszoniak ogromnie mi dopomógł, który bardzo stał po mojej stronie bardzo i fantastyczną tworzył rolę właśnie tego 'rewolucjonisty' w cudzysłowie, Wierchowieńskiego, dlatego że w rezultacie opowieść cała miała dlatego taką siłę, że to była historia: rodzice i dzieci. Rodzice, którzy reprezentują tę starą Rosję, ze wszystkimi konsekwencjami, z całym tym zakłamaniem, i młodzi, którzy dążą za wszelką cenę, żeby stworzyć nową sytuację i jak mówi Wierchowieński: 'Zwali się' – o Rosji – 'zwali się ta stara buda'. Nie! Mówi jeszcze inaczej, mówi: 'Najpierw pożary i zgliszcza, a potem zwali się stara buda i wzniesiemy gmach ze stali'. Muszę powiedzieć, że to były prorocze słowa, no bo Stalin wzniósł gmach ze stali w postaci Związku Radzieckiego, a oni tylko, że tak powiem, potrząsali tym gmachem starej budy systemu... systemu carskiego.

Ale nim te słowa padły ze sceny zbliżyliśmy się do premiery. A sztuka zaczynała się od części, która nie jest immanentnie w... nie znajduje się imanentnie w tekście Biesów. Mianowicie Dostojewski napisał jeszcze jeden rozdział, który się nazywa Spowiedź Stawrogina. No ale ponieważ bardzo tam pojawia się obyczajowo, jak na tamte czasy, wydarzenie, no, bez precedensu. Mianowicie Stawrogin opowiada jak zgwałcił małą dziewczynkę, w związku z tym ten rozdział został wyjęty z Biesów i ukazał się wydrukowany osobno. No ale żeby powiedzieć, kim jest Stawrogin, rzecz jasna, Dostojewski po to to napisał, że taka postać ma przewodzić tej nowej Rosji, on ma być nowym carem. W związku z tym odnalazłem ten rozdział i z niego zrobiłem początek przedstawienia. Spowiedź Stawrogina to jest pierwsza scena. No ale Stawrogin nie spowiada się samemu sobie, tylko spowiada się... mówi to do osoby duchownej. No to sobie pomyślałem, że najlepiej będzie jak on się będzie spowiadał do widowni, a ta osoba – jako przedstawiciel nas, którzy słuchamy tego, i mówimy: 'No nie, niemożliwe, ktoś mu musi przerwać' – wchodzi z widowni. I tak się stało. Jeden z bardzo znanych aktorów starszego pokolenia grał właśnie tego... tego rozmówcę Stawrogina i na generalnej próbie, na którą przyszło trochę młodej widowni, zaczęło się fantastycznie: bardzo Jan Nowicki z temperamentem i z taką gwałtownością i z taką desperacją wypowiedział początek tego... tej spowiedzi. Podniósł się Aleksander Fabisiak, który grał właśnie jego rozmówcę, i powiedział, że on samego siebie okłamuje, wszedł na scenę z widowni.

With all of these difficulties surrounding the adaptation which was being formed during the rehearsals, we were approaching our first performance. There were going to be plenty of surprises. Just before the first night, it turned out that the actor who was playing Captain Lebyadkin, a murky figure and a drinker, suddenly stopped coming to rehearsals having apparently disappeared somewhere. I thought to myself, things have gone too far if the actors are identifying with their characters to this extent. There were huge problems, huge conflicts - Wojciech Pszoniak helped me a great deal here, he was very much on my side and he created a fabulous role of the revolutionary, in inverted commas, Verkhovensky. As a result, the whole story had such power because it was a story about parents and children. The parents represented that old Russia with all the consequences and all its falsehood while the young ones are striving to create a new situation at all costs, and as Verhovensky says about Russia, 'This old hut will fall down.' No, he said something else. 'First, there will be fires and embers, and then this old hut will fall down and we will raise an edifice of steel.' I have to say that these were prophetic words because Stalin raised an edifice of steel in the form of the Soviet Union while all they did was to shake the the old hut of the tsarist system. But before these words were spoken from the stage, we approached our first performance. The play began with a fragment which wasn't an integral part of the text of The Devils. Namely, Dostoyevsky had written an additional chapter called Stavrogin's Confession. But it relates to an event that for those times was unheard of. Namely, Stavrogin tells how he raped a little girl, and so this chapter was taken out of The Devils and published separately. However, in order to tell who Stavrogin is, and it's obvious that this is why Dostoyevsky wrote this to show that this kind of person will lead the new Russia, that he is to be the new tsar. Therefore, I rediscovered this chapter and put it at the beginning of the play. Stavrogin's Confession is the first scene. However, Stavrogin isn't confessing to himself but to a man of the cloth. I decided that it would be best if he made his confession to the audience, while the person who represents us who are listening to this and saying, no - this is impossible, someone has to stop him - comes out of the audience. And this is what happened. A very well known actor of the older generation played Stavrogin's interlocutor, and in the dress rehearsal, which was attended by a young audience, this began brilliantly. Jan Nowicki launched into the beginning of this confession with passion and feeling and a kind of desperation. Aleksander Fabisiak, who played his interlocutor, stood up, saying that he's deceiving himself and came up onto the stage from the auditorium.

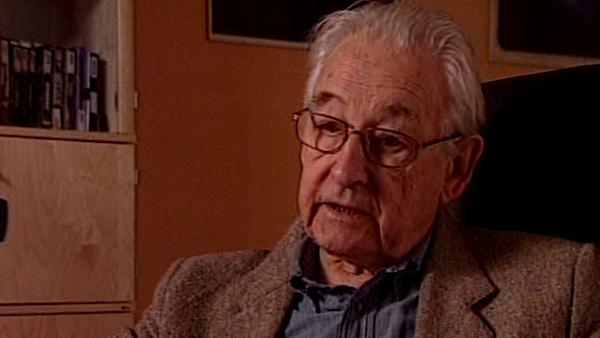

Polish film director Andrzej Wajda (1926-2016) was a towering presence in Polish cinema for six decades. His films, showing the horror of the German occupation of Poland, won awards at Cannes and established his reputation as both story-teller and commentator on Poland's turbulent history. As well as his impressive career in TV and film, he also served on the national Senate from 1989-91.

Title: Controversy over "Stavrogin's Confession"

Listeners: Jacek Petrycki

Cinematographer Jacek Petrycki was born in Poznań, Poland in 1948. He has worked extensively in Poland and throughout the world. His credits include, for Agniezka Holland, Provincial Actors (1979), Europe, Europe (1990), Shot in the Heart (2001) and Julie Walking Home (2002), for Krysztof Kieslowski numerous short films including Camera Buff (1980) and No End (1985). Other credits include Journey to the Sun (1998), directed by Jesim Ustaoglu, which won the Golden Camera 300 award at the International Film Camera Festival, Shooters (2000) and The Valley (1999), both directed by Dan Reed, Unforgiving (1993) and Betrayed (1995) by Clive Gordon both of which won the BAFTA for best factual photography. Jacek Petrycki is also a teacher and a filmmaker.

Tags: Capitan Lebyadkin, Verkhovensky Pyotr, Russia, Soviet Union, The Devils, Stavrogin's Confession, Wojciech Pszoniak, Joseph Stalin, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Jan Nowicki, Aleksander Fabisiak

Duration: 4 minutes, 43 seconds

Date story recorded: August 2003

Date story went live: 24 January 2008