NEXT STORY

The purpose of science

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

The purpose of science

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 61. Learning I'd won the Nobel Prize | 241 | 03:41 | |

| 62. The 'fallout' of winning the Nobel Prize | 261 | 05:58 | |

| 63. The purpose of science | 275 | 03:28 | |

| 64. The importance of pure research | 153 | 03:15 | |

| 65. The division of the Catholic University of Louvain | 118 | 03:55 | |

| 66. Louvain-la-Neuve | 98 | 02:45 | |

| 67. The International Institute of Cellular and Molecular Pathology | 127 | 04:46 | |

| 68. Collaboration within the ICP | 84 | 03:29 | |

| 69. Expanding and funding the ICP | 67 | 03:40 | |

| 70. Thierry Boon and the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research | 134 | 05:35 |

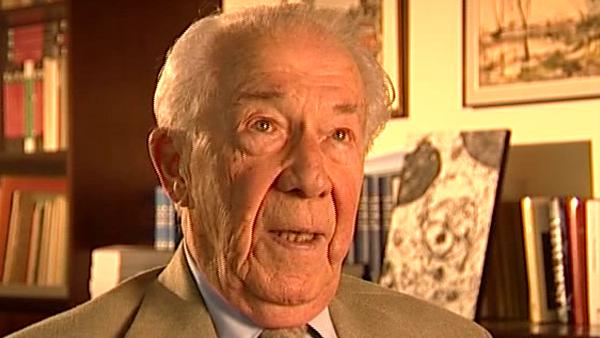

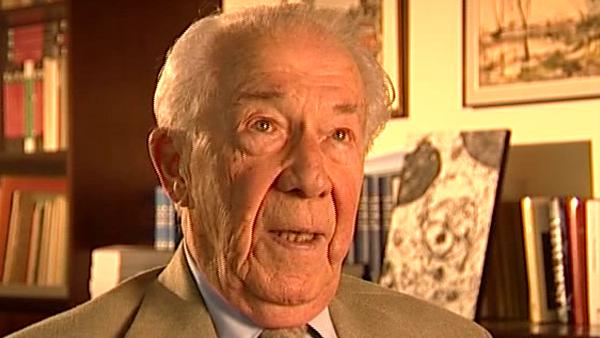

Well, there are many other aspects, of course, about Nobel Prize that... that are very gratifying, and I told you at the beginning... I told the story of the first Nobel ceremony we attended, my wife and I, and how I misguidedly told her that she would get a fur coat if and when I got a Nobel Prize. Well, she hadn't forgotten that, and so the first thing I had to do was to buy her the fur coat and, in fact, she had it when we went to Stockholm to attend the ceremony, and Theorell, my old boss and his wife very kindly came to the airport to meet us, and so on the way from the plane to the VIP room, where... we always get a very nice reception when you get there, the first thing that Margit Theorell noticed was the fur coat and she said to my wife, 'What a nice fur coat.’ And she told the story of, you know, the 1956... that was in fact only 18 years before... no, '46, 28 years before, and so she told the whole story, and the next morning there was a big headline. The first page of the Stockholm newspaper: ‘She had to wait 30 years for her fur coat!’ Because a journalist had heard – they were following us on the tarmac - and had heard the story and had immediately... so when we went into the... what you would call the lift and I've learnt to call the elevator in my American life, people would look at the fur coat and say, 'That's the fur coat, you know' –'De är pälset', that's in Swedish. Anyway, so that's one amusing aspect of the story and, of course, you get a little money and... in fact, a fair amount of money even when it's divided into three parts, and so I was able to indulge... a new piano. I hardly play the piano – as I say, I murder the piano more than I play – but in those days I used to play a lot and I enjoyed a good piano and also I was able to... we lived in the country in Belgium... to build a small swimming pool, which turned out to be an extremely useful as... as much as pleasant investment because my wife and I still swim every day in the summer nowadays, and I think it's about the only exercise that you can continue doing in a very old... at a very old age. I had to give up tennis, I had to give up skiing, to give up much of the sport... many of the sports I used to do, but swimming I can go on doing, and I think it's a very healthy exercise, so that again was a sort of fallout of the prize. The other fallouts are, in a way, pleasant and unpleasant: you get a little more attention... you get a little more attention from journalists, from media, which can be upsetting but is useful... I think it's about the only useful thing about the Nobel Prize because I mentioned this discrimination, which I think is... is sad, between people who had the same scientific distinction, of the same merits but, just for one reason or another, one gets the prize and the other one doesn't get the prize, but the prize has so much prestige that suddenly you create an enormous dissimilarity between people who really occupy the same level. And that... within the scientific community, I think that's a very... a very sad aspect of the whole thing. But the good aspect is that, because of this prestige, the Nobel Prize is about the only way in which scientists can really make themselves heard in the world of today. Somehow the public has little respect for science in general but, for some reason, Nobel means something to them, and that allows scientists – those who have been distinguished by the prize – to act as a spokesman for their... or spokeswoman, for their colleagues and to defend science in the world, to defend the scientific approach in the world, and this may be quite... quite important. So on the whole it's mixed feelings, but I would be dishonest if I did not admit that I was very pleased, and still am, to have been lucky enough to win this lottery ticket.

Belgian biochemist Christian de Duve (1917-2013) was best known for his work on understanding and categorising subcellular organelles. He won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1974 for his joint discovery of lysosomes, the subcellular organelles that digest macromolecules and deal with ingested bacteria.

Title: The 'fallout' of winning the Nobel Prize

Listeners: Peter Newmark

Peter Newmark has recently retired as Editorial Director of BioMed Central Ltd, the Open Access journal publisher. He obtained a D. Phil. from Oxford University and was originally a research biochemist at St Bartholomew's Hospital Medical School in London, but left research to become Biology Editor and then Deputy Editor of the journal Nature. He then became Managing Director of Current Biology Ltd, where he started a series of Current Opinion journals, and was founding Editor of the journal Current Biology. Subsequently he was Editorial Director for Elsevier Science London, before joining BioMed Central Ltd.

Tags: Nobel Prize

Duration: 5 minutes, 58 seconds

Date story recorded: September 2005

Date story went live: 24 January 2008