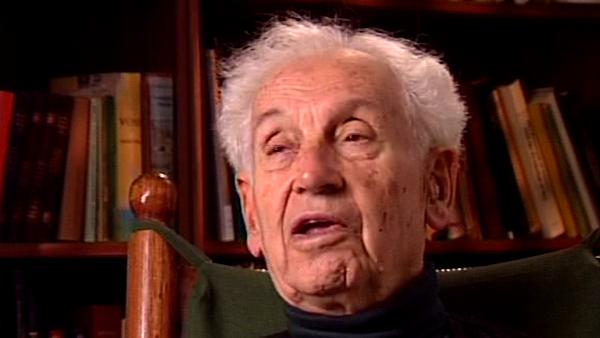

The traditional species concept in taxonomy always has been the so-called typological species concept. A species is that which is different from another species and then the word different, of course, always created difficulties but if in doubt call it a species, was sort of the feeling. But for many, many reasons I, and people that preceded me like Karl Jordan, whom I mentioned of the Rothschild Museum, and [Erwin] Stresemann and [Bernhard] Rensch in Germany, and some Russian authors, had rejected the typological species concept for strictly scientific reasons. They said as… or as I put in my more recent papers: if you want to find out what the species is, you have to ask what I call the Darwinian question. The question why? Why are there species? Why… why aren't all organisms able to… if they're at all similar to each other, to mate with each other and have offspring? Why is it all packaged in these separate units, species, and each of these packages is completely separated from the others and doesn't interbreed with it and doesn't mate with it? There must be some biological reason. And of course the reason, if you give it any thought is very obvious: if a individual with one genotype mates with an individual of a very different genotype, then the offspring would be hybrids that are either inviable or sterile or certainly very much inferior, and that particular individual loses offspring. In other words, it is selected against. So the real meaning of the species – that's the way I now put it in my papers – is that it is a protection of well-balanced, harmonious genotypes against being destroyed through mating with others that are very different from it. And that's the basic species concept and that is called the biological species concept, and that this biological species is usually found as a group of populations, of a group of interbreeding populations which is reproductively isolated, used to call it genetically isolated, from other such groups. And… so that is the biological species concept.

Sunday, 08 June 2025 03:27 AM

Hi