NEXT STORY

I helped redesign submarine escapes

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

I helped redesign submarine escapes

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11. Memory | 137 | 02:06 | |

| 12. My early work at the Applied Psychology Unit in Cambridge | 101 | 04:52 | |

| 13. I helped redesign submarine escapes | 117 | 05:21 | |

| 14. Torpedo practice and brass portholes in the wardroom | 86 | 01:56 | |

| 15. Working on neural noise at the Applied Psychology Unit | 84 | 04:49 | |

| 16. Why I got into psychology | 123 | 03:59 | |

| 17. Trying to set up a brain unit and moving to Edinburgh | 83 | 07:17 | |

| 18. Work at the Brain and Perception lab in Bristol | 129 | 06:21 | |

| 19. The case of Sidney Bradford | 896 | 06:09 | |

| 20. The Exploratory | 92 | 03:30 |

I stayed at Cambridge. I actually went into the what we call the APU, the Applied Psychology Unit, which was owned and run by the Medical Research Council, which is just, well, it’s on the fringe of Cambridge in Chaucer Road actually. It’s a big old country house, it had just been bought to turn into these laboratories and, in fact, there was rather an amusing story. The chap who bought it was a chap called Norman Mackworth who was actually a medical doctor who was a research worker in our department, the Department of Psychology, and he saw this house and he laid out his own money and bought this mansion assuming or hoping that the MRC would follow it up because he didn’t want to lose it. He was certain that this would make the most wonderful laboratory, it was a country house with lovely grounds, you see. It worked out, his gamble paid off. He bought the thing in one weekend, told the MRC, the Medical Research Council, that he’d bought this thing. They absolutely did their nut, as you can imagine, but finally coughed up, bought it and it’s, in fact, the biggest medical research laboratory outside London actually, and has been very successful indeed. I started there and it was a wonderful laboratory. It combined people having abstract general ideas with very, very practical problems and I think that mixture of the theoretical and the practical, well, it certainly suited me. I think it suited a lot of people very, very well. I remember I wrote a long essay about the brain as an induction machine, following really from Bertrand Russell and thinking about induction and all the rest of it and I still think these problems about how you gain knowledge by instances, generalising, then creating an hypothesis, which you then test, which go on in science is really what the brain also does. We are sort of little scientists inside our heads to a great extent. Anyway, I wrote an essay on that which went on and on but at the same time I did practical things, some quite dramatic. I spent a year working on escaping from submarines for the navy. Sir Frederick Bartlett who was my professor, wonderful man, and he was again a person I respect totally looking back on him, he seconded me to the navy for a year actually at Whale Island in Portsmouth. I used to go down in the submarine and then we did a big experiment where we changed the atmosphere, we increased the CO2, reduced the oxygen, as though one was in a stricken submarine, you see, and then we had, I designed escape gear, a replica of the 42 operations required to get out of a submarine for each man using the twill trunk system, no, sorry, using a gun tower system, where each chap had to get into a gun tower, open the lower hatch, get into it, close it, put oxygen into it, put the upper one up, then you had to drain the water out- 42 separate operations for each person actually to get out of this thing. Meanwhile you had to wait to be discovered because if you got out of the submarine when you were at the bottom of the sea, nobody knew you were there, you were going to get drowned, no point in doing it. So what they did, they sat down there waiting to hear the screws of surface ships circling because, you won’t believe this, but the sonar thing was on the bow of the submarine. The first thing that happened was that broke off if it hit the deck, you see, at the bottom of the sea, and so they lost communication. It was quite extraordinary. The only communication was listening for the screws of the surface vessel so what I was working on was how long one should wait to be discovered down there, you see, by surface ships as the oxygen gradually failed and the CO2 gradually took over your consciousness, you know. Given that it was 42 operations for each chap, I mean, and then you had about maybe 50 chaps getting out of this thing, how long could you wait to start the escape? It's quite interesting. So I worked on that.

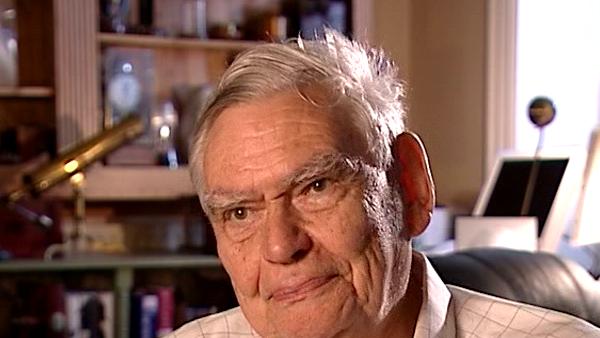

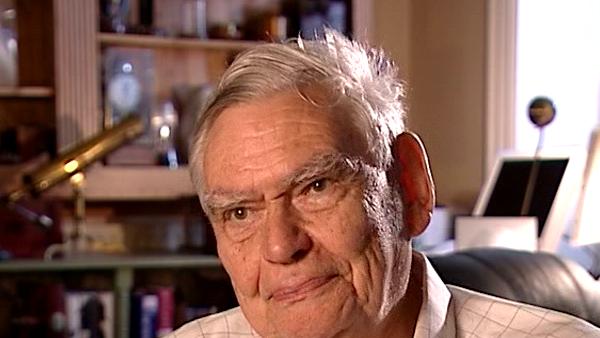

The late British psychologist and Emeritus Professor of Neuropsychology at the University of Bristol, Richard Gregory (1923-2010), is well known for his work on perception, the psychology of seeing and his love of puns. In 1978 he founded The Exploratory, an applied science centre in Bristol – the first of its kind in the UK. He also designed and directed the Special Senses Laboratory at Cambridge which worked on the perceptual problems of astronauts, and published many books including 'The Oxford Companion to the Mind', 'Eye and Brain' and 'Mind in Science'.

Title: My early work at the Applied Psychology Unit in Cambridge

Listeners: Adam Hart-Davis Sally Duensing

Born on 4 July 1943, Adam Hart-Davis is a freelance photographer, writer, and broadcaster. He has won various awards for both television and radio. Before presenting, Adam spent 5 years in publishing and 17 years at Yorkshire Television, as researcher and then producer of such series as Scientific Eye and Arthur C Clarke's World of Strange Powers. He has read several books, and written about 25. His latest books are Why does a ball bounce?, Taking the piss, Just another day, and The cosmos: a beginner's guide. He has written numerous newspaper and magazine articles. He is a keen supporter of the charities WaterAid, Practical Action, Sustrans, and the Joliba Trust. A Companion of the Institution of Lighting Engineers, an Honorary Member of the British Toilet Association, an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Photographic Society, the Royal Society of Chemistry, the Society of Dyers and Colourists, and Merton College Oxford, and patron of a dozen charitable organizations, Adam has collected thirteen honorary doctorates, The Horace Hockley Award from the Institute of Scientific and Technical Communicators, a Medal from the Royal Academy of Engineering, the Sir Henry Royce Memorial Medal from the Institute of Incorporated Engineers, and the 1999 Gerald Frewer memorial trophy of the Council of Engineering Designers. He has no car, but three cycles, which he rides slowly but with enthusiasm.

Sally Duensing currently is involved in perception exhibition work and research on science and society dialogue programmes and is working with informal learning research graduate students and post-docs at King's College, London. In 2000 she held the Collier Chair, a one-year invited professorship in the Public Understanding of Science at the University of Bristol, England. Prior to this, for over 20 years she was at the Exploratorium, a highly interactive museum of science, art and perception in San Francisco where she directed a variety of exhibition projects primarily in fields of perception and cognition including a large exhibition on biological, cognitive and cultural aspects of human memory.

Duration: 4 minutes, 52 seconds

Date story recorded: June 2006

Date story went live: 02 June 2008