When I was at Cambridge, I really had a sort of perfect life. I had a wonderful laboratory. We built a new wing on the building, we shared the building with physiology and there was a bit of a war that always went on between the physiologists and the psychologists and we always came off second best because they were sort of superior beings to us, you know, they sort of pecked us, so to speak, but I actually was amazingly lucky because I had the whole top floor of this new wing of the building and I ran this as a laboratory, it was called Special Senses Laboratory and I built an anechoic chamber in it for sound experiments and I had a dark room, a very nice workshop of my own in which I could make things and also it could help the students quite a lot. It was very useful actually to have that. And then, not only that, I actually had a telescope in the observatory, in Cambridge Observatory, 'cause I got this idea for taking photographs through turbulence of the atmosphere and improving them while I was at Cambridge and they gave me the oldest and smallest telescope in the observatory, a beautiful telescope, it was, I think, 99 years old at that time and in its own little building, it was absolutely delightful. I had such fun with that and I modified it, set it up for our apparatus and I worked with a very good engineer, Steven Salter, who worked with me, for me, and we built this very interesting apparatus actually, which I spent years on and in the end tried it out in New Mexico and Arizona on big telescopes and so on. It really was a very, very interesting project, how to get better pictures through turbulence of the atmosphere, it was a wonderful problem. Incidentally, that was financed by NASA before, no, by the American Air Force, just before NASA, for the moon landing, because we tried to get better pictures of the moon for choosing the landing site in 69 so all of this was in the 60s leading up to the moon landing. Anyway, all that was going on, you see, and I was top of my form really at that time, and then I got interested in artificial intelligence because the physiologists were not getting into the brain and I got fed up with this so I got bored with the peripheral physiology, the retina and all that, I wanted to know what on earth was going on in the head partly because of the philosophy of it, you see. So the idea of making computers intelligent and seeing things was amazing because you could then extend the philosophy into technology. Again I thought that technology and philosophy and physiology and psychology were all, you know, helped each other and if we got this going it would be fantastic. So we tried to start a brain institute in Cambridge, failed because they’d got two subjects going at that time, ethology was one and there was another one, I can’t think for a second what it was, but there were two new subjects so that we couldn’t start a third one so we tried to go to Brighton and that didn’t work for various reasons so in the end Michael Swan, the Vice-Chancellor, set us up in Edinburgh and I moved with Christopher Longuet-Higgins, we were both fellows at Corpus. He was a brilliant chemist, theoretical chemist and we started this department with Donald Michie who was already there in which we built the robot called FREDDY and it was a big department. We had 60 academics in it and lots and lots of money and it was only partially successful. We were too early. Computers were simply not up to it and, quite frankly, we weren’t up to it. I mean we didn’t know how to programme computers. Christopher learned very well. I never did learn properly because I was made head of department, I had to administer it, which I’ve never liked doing. Christopher and Donald didn’t get on terribly well together which was a problem and all sorts of other problems and I really missed Cambridge. I had all this wonderful set up in Cambridge and my fellowship and free port in the evenings and all that, and there we were in the bleak North, you know, quite honestly. I found Edinburgh, in a way, an amazing and beautiful and wonderful place but, golly, it’s cold, it really is. I never really settled down properly in Edinburgh. At any rate, we had this sort of dream of trying out our ideas, philosophical and technical, with new technology in order to see whether we couldn’t make an intelligent machine which could see things. We were the first in Europe and we worked with two American departments that had just got going, Stanford and MIT, and every year we came together in a big workshop. We wrote a great big book each year, which was a sort of bible really of the subject, and there was some good work done, some of it was very good. Some of our students were excellent and it’s an ongoing department, I mean it’s a major department now so it wasn’t a waste of time doing it but it didn’t suit me actually, it really didn’t, particularly after Cambridge. So I decided to try and run my own small laboratory again and moved to Bristol.

Why Bristol?

Well, A. I didn’t know Bristol, B. it was near London and I got fed up being far up in the north, and I was offered a very nice laboratory actually in the Medical School without having to build anything, I could just move in and I got fed up with dealing with buildings. Actually, it was an incredibly funny thing that might amuse you. When we went to Edinburgh, we were offered a very nice, large church for our laboratory belonging to the Church of Scotland, it had been deconsecrated. Then they heard we were going to build a robot and the idea of a robot walking up the aisle was just too much and they withdrew it. We got up there with no laboratory. We had plans and everything, they completely went down the drain and we were there with no laboratory at all and in the end we got an army building given to us by Michael Swan. Michael said we can get the chaps out in six months, they’re still there, you know. It was bizarre actually. So I gave up, you know, Cambridge and my fellowship, my very nice laboratory which I really loved with not a lot of administration and so on, for administering in a place that was far away from anywhere I wanted to be, freezing cold, but with very bright, excellent students and colleagues, you know, and we did, after all, start a new subject, which is quite a difficult thing to do.

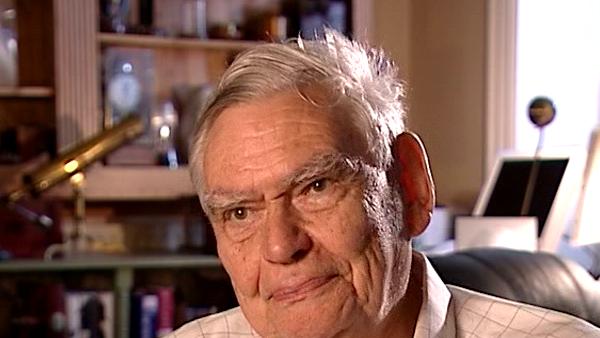

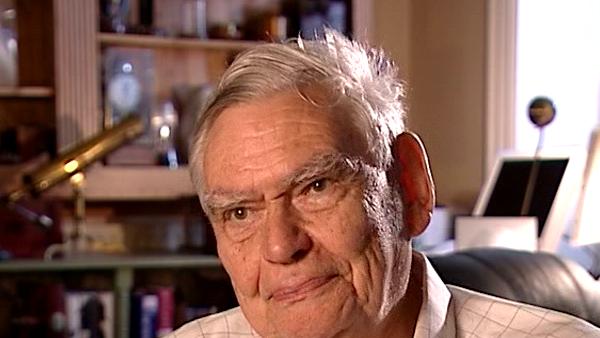

The late British psychologist and Emeritus Professor of Neuropsychology at the University of Bristol, Richard Gregory (1923-2010), is well known for his work on perception, the psychology of seeing and his love of puns. In 1978 he founded The Exploratory, an applied science centre in Bristol – the first of its kind in the UK. He also designed and directed the Special Senses Laboratory at Cambridge which worked on the perceptual problems of astronauts, and published many books including 'The Oxford Companion to the Mind', 'Eye and Brain' and 'Mind in Science'.

Title: Trying to set up a brain unit and moving to Edinburgh

Listeners:

Adam Hart-Davis

Sally Duensing

Born on 4 July 1943, Adam Hart-Davis is a freelance photographer, writer, and broadcaster. He has won various awards for both television and radio. Before presenting, Adam spent 5 years in publishing and 17 years at Yorkshire Television, as researcher and then producer of such series as Scientific Eye and Arthur C Clarke's World of Strange Powers. He has read several books, and written about 25. His latest books are Why does a ball bounce?, Taking the piss, Just another day, and The cosmos: a beginner's guide. He has written numerous newspaper and magazine articles. He is a keen supporter of the charities WaterAid, Practical Action, Sustrans, and the Joliba Trust. A Companion of the Institution of Lighting Engineers, an Honorary Member of the British Toilet Association, an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Photographic Society, the Royal Society of Chemistry, the Society of Dyers and Colourists, and Merton College Oxford, and patron of a dozen charitable organizations, Adam has collected thirteen honorary doctorates, The Horace Hockley Award from the Institute of Scientific and Technical Communicators, a Medal from the Royal Academy of Engineering, the Sir Henry Royce Memorial Medal from the Institute of Incorporated Engineers, and the 1999 Gerald Frewer memorial trophy of the Council of Engineering Designers. He has no car, but three cycles, which he rides slowly but with enthusiasm.

Sally Duensing currently is involved in perception exhibition work and research on science and society dialogue programmes and is working with informal learning research graduate students and post-docs at King's College, London. In 2000 she held the Collier Chair, a one-year invited professorship in the Public Understanding of Science at the University of Bristol, England. Prior to this, for over 20 years she was at the Exploratorium, a highly interactive museum of science, art and perception in San Francisco where she directed a variety of exhibition projects primarily in fields of perception and cognition including a large exhibition on biological, cognitive and cultural aspects of human memory.

Duration:

7 minutes, 17 seconds

Date story recorded:

June 2006

Date story went live:

02 June 2008