Well, I found from not my work, the work of J.C.R Licklider who is an American physiologist, that the information, it’s a little bit technical, the information in speech is not at the peaks, wiggle wiggle way, it’s at the crossover where the energy crosses over at zero energy access where the sound waves, pressure waves, of course, in the air are going plus and minus, nothing in the middle, and then it crosses over. Now, it’s the moment that it crosses over the zero energy that gives you the information. Put it another way, you’ve got the drum in your ear, goes in and out, it’s when it’s changing direction that you get the signal and the fact that it moves a long way in or out doesn’t matter so much. It matters for music but not for speech. So what I wanted to do was to reduce the amplitude of the wave in the ear effectively to then amplify the middle bit where the information is but there’s a lovely, interesting, technical problem that if you limit the amplitude of a wave you don't just get rid of that energy it gets created as harmonics and it sounds distorted and sounds perfectly horrible. So I couldn’t simply limit the wave like that for peak clipping without all this distortion stuff coming in. Then I thought, well, is there a way of doing it? Now, this is really intriguing because the mathematics of it tells you it’s impossible that any wave, when you limit it, the energy has to go somewhere and it goes into these harmonics so it’s impossible but, do you know what, it isn’t impossible. The trick is this and it’s really amusing, this, you take the speech band, you know, from sort of 50 cycles up to, let’s say, 300, 3,000 cycles, let’s say something of that order, then you move the whole speech band outside the speech range. That is, you make it inaudible by putting into, let’s say, 100 kilocycles. Now, you could do that using a radio technique, which is called modulation and heterodyning. You modulate the carrier, that is, you have a carrier which you make wiggle up and down with the information on it, but when you remove the carrier to a different frequency, you’ve still got the same wiggle, the same information, but it’s no longer in the speech band. So what I did, I did the processing out side the speech band and the same mathematics applies, that you generate all these rotten harmonics and things but you can’t hear them because they are right outside the speech band. You then heterodyne it back down again into the speech band, filtering off the rubbish, which you can do because it’s separated. Then you get a lovely thing, you get speech which is not distorted but which is limited in the wiggles, in the amplitude, therefore you can amplify the bits in the middle where the information is without the distortion of normal peak limiting. So that was the idea for this hearing aid and we made it. We made an experimental one and then we made, I think it was 30 or 50 portable ones you could put in a pocket. There were never that small, you know, they were sort of six inches big but this is before micro components were available, but they were reasonable. You could put in a pocket, okay, and I tried these out and on the whole it was successful. I think it is good and it prevents blasting the ear to pieces, many hearing aids simply damage the ear by, you know, just simply putting loud noises into the ear which is the last thing the ear wants, not to get further damaged. So A. it protects the ear, B. it increases the actual signals it’s getting of speech, I’m not talking about music, but of speech, and it seemed to me a really rattling good idea all round. So I took this to industry and I couldn’t find anybody who wanted to make it because the hearing aid people were stuck with their hearing aids, they didn’t want to try something different, and an electronic firm didn’t want to get into hearing aids which was its own sort of industry and mainly concerned, by the way, with making everything smaller and smaller and smaller until it doesn’t work properly, in my view. That’s my view. So, but in the end I did find a firm which took it on and it was really annoying. It was all going fine, in the end an administrative decision was made that they didn’t want to get into hearing aids and it was abandoned so one of the real failures of my whole life, and regrets, is that this thing never got manufactured. I deeply regret it because hearing loss is a hell of a problem as you get older and well over a million people in Britain, probably two million, you know, suffer from it. Careers could get ruined, like solicitors, they can no longer hear what’s going on and so on, and it’s just a terrific problem. I think it needs a lot more research, honestly.

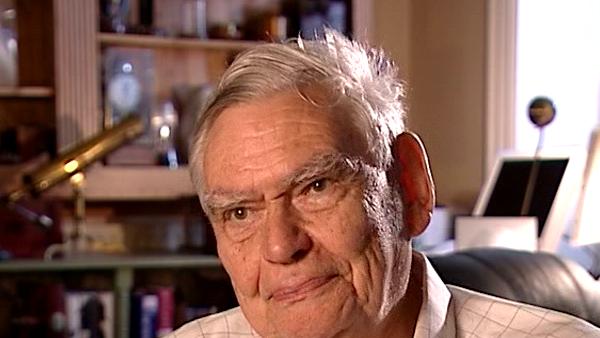

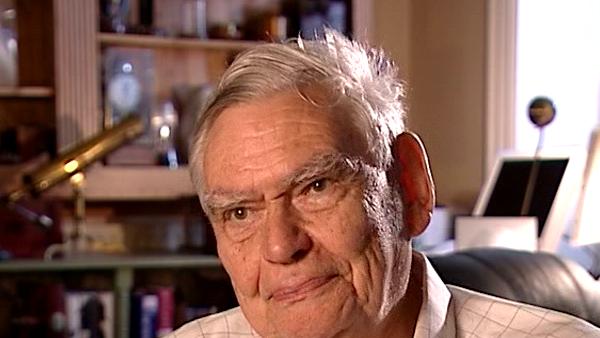

The late British psychologist and Emeritus Professor of Neuropsychology at the University of Bristol, Richard Gregory (1923-2010), is well known for his work on perception, the psychology of seeing and his love of puns. In 1978 he founded The Exploratory, an applied science centre in Bristol – the first of its kind in the UK. He also designed and directed the Special Senses Laboratory at Cambridge which worked on the perceptual problems of astronauts, and published many books including 'The Oxford Companion to the Mind', 'Eye and Brain' and 'Mind in Science'.

Title: The hearing aid (Part 2)

Listeners:

Sally Duensing

Adam Hart-Davis

Sally Duensing currently is involved in perception exhibition work and research on science and society dialogue programmes and is working with informal learning research graduate students and post-docs at King's College, London. In 2000 she held the Collier Chair, a one-year invited professorship in the Public Understanding of Science at the University of Bristol, England. Prior to this, for over 20 years she was at the Exploratorium, a highly interactive museum of science, art and perception in San Francisco where she directed a variety of exhibition projects primarily in fields of perception and cognition including a large exhibition on biological, cognitive and cultural aspects of human memory.

Born on 4 July 1943, Adam Hart-Davis is a freelance photographer, writer, and broadcaster. He has won various awards for both television and radio. Before presenting, Adam spent 5 years in publishing and 17 years at Yorkshire Television, as researcher and then producer of such series as Scientific Eye and Arthur C Clarke's World of Strange Powers. He has read several books, and written about 25. His latest books are Why does a ball bounce?, Taking the piss, Just another day, and The cosmos: a beginner's guide. He has written numerous newspaper and magazine articles. He is a keen supporter of the charities WaterAid, Practical Action, Sustrans, and the Joliba Trust. A Companion of the Institution of Lighting Engineers, an Honorary Member of the British Toilet Association, an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Photographic Society, the Royal Society of Chemistry, the Society of Dyers and Colourists, and Merton College Oxford, and patron of a dozen charitable organizations, Adam has collected thirteen honorary doctorates, The Horace Hockley Award from the Institute of Scientific and Technical Communicators, a Medal from the Royal Academy of Engineering, the Sir Henry Royce Memorial Medal from the Institute of Incorporated Engineers, and the 1999 Gerald Frewer memorial trophy of the Council of Engineering Designers. He has no car, but three cycles, which he rides slowly but with enthusiasm.

Duration:

5 minutes, 46 seconds

Date story recorded:

June 2006

Date story went live:

02 June 2008