Yeah, I'd quite like to talk about, if it wouldn’t be a bore, you know, sort of the central theme that I’ve worked on really, really thought about, really all my academic life and that is what can be called bottom up and top down. This is a shorthand phrase but it’s quite simple. What it really means is, say, in vision, it applies to all the senses, but in vision you’ve got signals coming into the brain from the eye down the million fibres of the optic nerve, if you like, into the brain, from the real world outside you, and some theories of perception say that’s it, that’s all there is. It’s just a whole load of inputs from the senses, touch, vision, hearing, the brain analyses, responds to these sensations represented by what are called action potentials, that is, signals in the nerve, rather like Morse code, dots and dashes of Morse code, and then somehow the brain reads these dots and dashes, if you like, these little signals, but the thing is, how does it read the signals and make sense of them unless it’s got knowledge of what the signals might mean? For example, if you get a telegram and it says my- your aunt, arriving Thursday. You’ve got to know what an aunt is, you’ve got to know what arriving is, you’ve got to know what Thursday is, otherwise it’s just a load of dots and dashes of Morse code and completely meaningless. You always have to relate the information received to a load of knowledge in store, if you like. Now, I think the same is true in vision and you can call this bottom up, well, you can call this signals coming in and then also knowledge interpreting the signals so you’ve really got top down processing from knowledge, if you like, bottom up signals, coming in from the eyes. The real question is, the ratio of how much do we see things in terms of the available information from the world at the present moment? How much is it dependent on information from the past to interpret those signals and then when the knowledge is wrong or not applicable or might be out of date, how far do you see things wrongly? How far are illusions and errors due not to the signalling going wrong in the eye, if you like, but to the knowledge not being appropriate or not being used correctly? Now, ophthalmologists are really concerned, you know, with getting glasses, spectacles, for your eyes to correct the image so that you get good images but actually, you know, if the knowledge is just as important or even more important, you need to consult somebody who knows about the brain, somebody who knows about the mind, just as much as an ophthalmologist when you’ve got problems of seeing. So I’ve really spent most of my life actually on just this and when I started, and this is really quite amazing, there was no physiological knowledge that knowledge that- that top down existed in the brain. We’ve guessed that it must but there were no known fibres from the known parts of the brain which handle knowledge, rules, cognition, into the visual system. It was all thought to come from the eye into the brain directly, and then years later, only about 12 years ago, it was discovered there were actually more nerve fibres coming down into the visual system actually to relay stations just behind the eyes called lateral geniculate bodies, there are more fibres coming down from the knowledge parts of the brain, than there are from the eyes into the visual system. So it’s quite incredible, so it moved from everything is from the eyes to, golly, there’s actually more from the higher levels of the brain, the cortex, than from the eyes, the vision. Well, in a way, do you know, we guessed that from our experiments on illusions years, years before the anatomy was discovered, but there was a bit of a sort of tension here between the psychologists working on the stuff with illusions and so on, and the physiologists or anatomists looking at the brain structures and suddenly the two have come together and we now know that actually the experiments on illusions and things were actually right. They showed that there’s a huge contribution from knowledge into interpreting the signal for seeing and we now know that the anatomical pathways actually do exist for this influence. It’s really quite a nice case, and you often get this in science. You get different disciplines developing their bit and it doesn’t fit what other disciplines are saying, and then get this sort of conflict and you go to a conference and you can really get a lot of angst about this, it takes a lot of beers to sort it out, and then suddenly somebody gets a breakthrough and they find the missing link and then it reconciles apparently different views. It’s very much how science works actually. So you often get sort of competing camps, you get schools of thought, and the case for vision, there’s a very famous American psychologist called J.J. Gibson, who thought that perception is simply direct, that you just got information coming in and that’s it and I never agreed with that through having worked with illusions, and I always thought it was highly indirect, that perceptions about hypothesis just as indirect as hypothesis in science to the world outside and this sort of indirect view and the direct view have been a great controversy for years and years in thinking about perception. And, well, I think I was right, actually I still do.

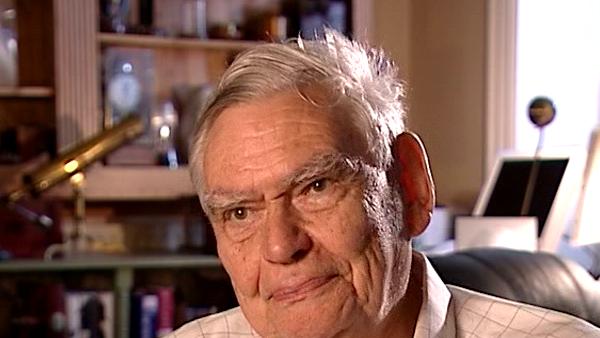

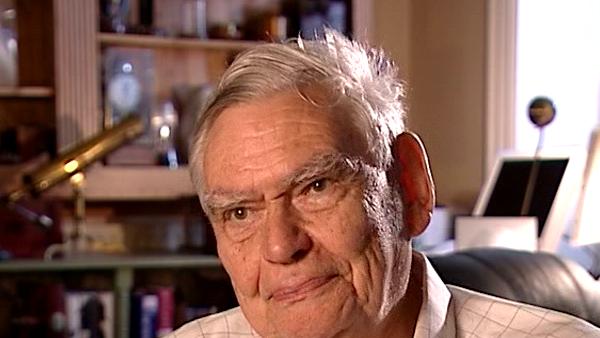

The late British psychologist and Emeritus Professor of Neuropsychology at the University of Bristol, Richard Gregory (1923-2010), is well known for his work on perception, the psychology of seeing and his love of puns. In 1978 he founded The Exploratory, an applied science centre in Bristol – the first of its kind in the UK. He also designed and directed the Special Senses Laboratory at Cambridge which worked on the perceptual problems of astronauts, and published many books including 'The Oxford Companion to the Mind', 'Eye and Brain' and 'Mind in Science'.

Title: Bottom up and top down

Listeners:

Adam Hart-Davis

Sally Duensing

Born on 4 July 1943, Adam Hart-Davis is a freelance photographer, writer, and broadcaster. He has won various awards for both television and radio. Before presenting, Adam spent 5 years in publishing and 17 years at Yorkshire Television, as researcher and then producer of such series as Scientific Eye and Arthur C Clarke's World of Strange Powers. He has read several books, and written about 25. His latest books are Why does a ball bounce?, Taking the piss, Just another day, and The cosmos: a beginner's guide. He has written numerous newspaper and magazine articles. He is a keen supporter of the charities WaterAid, Practical Action, Sustrans, and the Joliba Trust. A Companion of the Institution of Lighting Engineers, an Honorary Member of the British Toilet Association, an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Photographic Society, the Royal Society of Chemistry, the Society of Dyers and Colourists, and Merton College Oxford, and patron of a dozen charitable organizations, Adam has collected thirteen honorary doctorates, The Horace Hockley Award from the Institute of Scientific and Technical Communicators, a Medal from the Royal Academy of Engineering, the Sir Henry Royce Memorial Medal from the Institute of Incorporated Engineers, and the 1999 Gerald Frewer memorial trophy of the Council of Engineering Designers. He has no car, but three cycles, which he rides slowly but with enthusiasm.

Sally Duensing currently is involved in perception exhibition work and research on science and society dialogue programmes and is working with informal learning research graduate students and post-docs at King's College, London. In 2000 she held the Collier Chair, a one-year invited professorship in the Public Understanding of Science at the University of Bristol, England. Prior to this, for over 20 years she was at the Exploratorium, a highly interactive museum of science, art and perception in San Francisco where she directed a variety of exhibition projects primarily in fields of perception and cognition including a large exhibition on biological, cognitive and cultural aspects of human memory.

Duration:

6 minutes, 25 seconds

Date story recorded:

June 2006

Date story went live:

02 June 2008