NEXT STORY

Continued testing with the Halifax and tragedy strikes

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Continued testing with the Halifax and tragedy strikes

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 21. Orders to move to Bomber Command: A lucky escape | 189 | 02:07 | |

| 22. Writing a paper on radar echoes from cosmic ray showers | 208 | 03:04 | |

| 23. Working with the Admiralty | 138 | 02:52 | |

| 24. Being given the job of improving the bombing success rate | 149 | 07:52 | |

| 25. Getting the radar system into a Halifax bomber | 171 | 03:23 | |

| 26. Testing the radar system in the Halifax and a threat from the... | 153 | 04:28 | |

| 27. Continued testing with the Halifax and tragedy strikes | 1 | 168 | 04:38 |

| 28. A meeting with Winston Churchill and Robert Renwick | 304 | 04:44 | |

| 29. Don Bennett and the RAF Pathfinder Force | 262 | 01:26 | |

| 30. Continued work on H2S | 164 | 01:21 |

So, I still did not see the problem as difficult. It's the worst misjudgement I've ever made in my life. The equipment after all, I think my reasoning was not unjustified. We had made the essential equipment. The centimetre transmitter was being manufactured. The receiver was all right. All I had to do was to make a new display unit for the navigator and connect this to the rotating scanner underneath the belly of the aircraft. They had a prototype equipment in a Halifax bomber at Hurn airport in April of 1942. Amazing speed at which these things were done. I arrived at Hurn airport to take off and see on this initial flight and to my astonishment was met by the Deputy Chief of Air Staff, who had been told to accompany me to see how the equipment worked.

Well, this was really incredible. I need hardly say the equipment did not work. I mean, on the first flight the power supply broke down and we landed again but it was that high pressure absolutely hindered any sensible development of the problem, because it turned out that the polar diagram of this truncated paraboloid rotating in the cupola under the fuselage of the heavy bomber, the polar diagram was atrocious and not only that, but the original echoes which we convinced people that it would work had been carried out of the height of 10,000 feet and the Halifax was flying at 20,000 feet. So that was the problem that besetted us, and we made these early flights and really we were bedeviled by the breakdown of the equipment because of flying at higher altitudes by the rotten polar diagram, the fades which constantly occurred because of the peculiar polar diagram of the system.

And then a most awful thing happened. We... in February of 1942, we had... not we, I mean the country... the air force, and so we had designed to make a commando raid on Brunevar, to capture some German radar equipment to see how they were getting on and one of our staff was engaged. He was put into uniform and went on this raid. Now, the Brunevar raid was successful but it had the most terrible effect on the Germans. They assembled a parachute division on the Cherbourg peninsula and we learnt that their intention was to capture us on... we were working on the Purbeck Peninsula. We were ordered by Churchill to get out before the next full moon. Every night we had to drive this highly secret equipment, using the magnetron beyond the Corfe gap and so in late April, early May, after an enormous amount of trouble and investigation, we all moved to Malvern College. The second time the boys had been evacuated and entirely took over Malvern College, using an airfield at Defford, about seven miles away for our airborne gear.

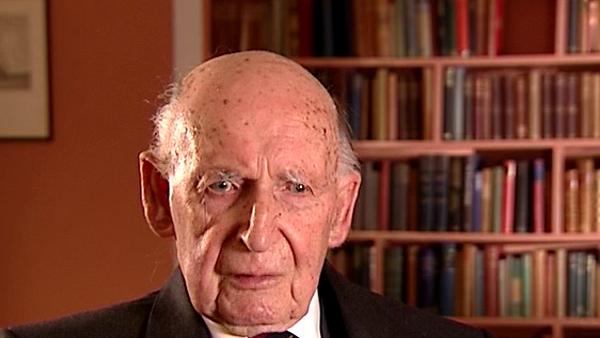

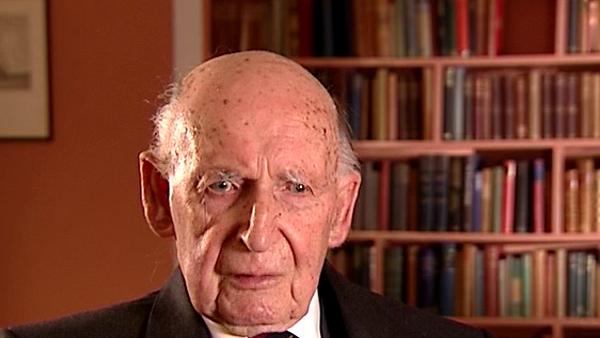

Bernard Lovell (1913-2012), British radio astronomer and founder of the Jodrell Bank Observatory, received an OBE in 1946 for his work on radar, and was knighted in 1961 for his contribution to the development of radio astronomy. He obtained a PhD in 1936 at the University of Bristol. His steerable radio telescope, which tracked Sputnik across the sky, is now named the Lovell telescope.

Title: Testing the radar system in the Halifax and a threat from the Germans

Listeners: Megan Argo Alastair Gunn

Megan Argo is an astronomer at the University of Manchester's Jodrell Bank Observatory researching supernovae and star formation in nearby starburst galaxies. As well as research, she is involved with events in the Observatory's Visitor Centre explaining both astronomy and the history of the Observatory to the public.

Alastair Gunn is an astrophysicist at Jodrell Bank Observatory, University of Manchester. He is responsible for the coordination and execution of international radio astronomical observations at the institute and his professional research concerns the extended atmospheres of highly active binary stars. Alastair has a deep interest and knowledge of the history of radio astronomy in general and of Jodrell Bank in particular. He has written extensively about Jodrell Bank's history.

Tags: Handley Page Halifax, Hurn Airport, Brunevar, Cherbourg Peninsula, Isle of Purbeck, Malvern College, Winston Churchill

Duration: 4 minutes, 28 seconds

Date story recorded: January 2007

Date story went live: 05 September 2008