NEXT STORY

People at Smith, Kline & French and paying back taxes

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

People at Smith, Kline & French and paying back taxes

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 41. JD Bernal, politics, and science | 101 | 02:28 | |

| 42. Scientometrics, JD Bernal and Joshua Lederberg | 99 | 06:15 | |

| 43. Moving to Philadelphia to work for Smith, Kline & French | 55 | 06:56 | |

| 44. People at Smith, Kline & French and paying back taxes | 47 | 04:34 | |

| 45. My son Stefan | 121 | 07:05 | |

| 46. My son Josh | 110 | 07:50 | |

| 47. Job security and outsourcing | 47 | 05:07 | |

| 48. Working with Irving H Sher | 82 | 03:00 | |

| 49. The peccadillos of Irving H Sher | 67 | 02:38 | |

| 50. Using abstracts and changes in the company | 43 | 02:49 |

It was Ted Herdegen, who later on became one of my closest friends, and to whom the first issue of the Index Chemicus is dedicated, if you went back. I guess online it wouldn’t be possible for people to see those things quite as easily as when they were in print. Yeah, Ted Herdegen had come to visit me, and only very briefly from having visited the Welch Medical Imaging Project, and when Smith, Kline & French was a relatively small local pharmaceutical company, and the president, the owner, the leading executives at the time were typical mainline Wasps, you know, and Smith, Kline & French was basically a Waspy company, although I later found out that they had one other guy by the name of Greenberg who stayed there quite a while, but he was a rarity. Anyhow, they started to become a larger company. They were the ones that sold Dexedrine and products like that. I think at that time Dexedrine was used for people with colds, it was like a nasal spray. So, they were very big in the over the counter market. I don’t know how many prescription drugs they sold. Ted Herdegen had worked as a chemist for them many years before in the lab that apparently was located downtown, in Philadelphia somewhere. But when I came to Philadelphia, when he... when I came to work for them, they had a brand new building that is still there, 15 Spring Gardens. It was, you know, like a four or five storey building, and they had tableting and manufacturing in their offices and so forth, and in the labs. So they had a man by the name of Wes Scull, the director of chemical research, one of the medical research directors, had gone to Europe to find potentially new products, and they found this drug which was used for the treatment of nausea in pregnant women. It was a, I believe, a CNS depressant. But somehow when they did some testing and they found out it was a very effective antidepressant drug, which was peddled under the name of thorazine. And thorazine is even used to this day for a variety of conditions, I think it may be even like a mild sedative, relaxant, CNS, relaxant or whatever. The year that I came here, 1954, the drug had made the cover of Time magazine, and this company suddenly became a superstar pharmaceutical company. I didn’t have any stock or anything, and I don’t even know if it was on the, you know, stock market or not. This drug made them a fortune. And apparently what had accumulated was a large number of kinds of informal, formal case reports on the drug. And what they wanted, Ted and the head of the department at Smith Kline was a fellow named Henry Longnecker, who was from the mainline family, as I recall, and they realised that they needed to have a more efficient way of processing all of the reports they were getting on the use of the drug. So, Ted had known that I was considered as the punch card guru in those days, and he had called me when I was still at library school. I think I said yesterday that I was planning to go to Georgetown with Casimir and Léon Dostert, but that fizzled, and so he hired me and I came down here. And what we did was we set up a pretty straightforward coding system where each position on the card represented some particular side effect. And what they wanted to do, basically, was to do statistical analyses to see how often certain side effects occurred. There were things that apparently... you couldn’t draw those conclusions from just working with the drugs, some doctors might have noticed it. But it turned out that there were several significantly frequent side effects, like dermatitis and so forth. So, that was one of the reasons they brought me down, as somebody to set up this punch card system, so we had these coding sheets. And what we did was first of all we got all these individual letters or documents that were given to the detail men who, you know, sold the drug for the company, the doctors gave them these reports, and then furthermore there was a lot of literature that had been published on the drug, even before it was marketed for the purposes they were selling it, you know, to treat nausea and vomiting. And so we went into the literature, and whenever there was a case report in the published article we would treat that as though the doctor had submitted it, and that was how we used the published literature to build up sort of like an early evidence-based medicine, you know, to analyse the effects. Also they used it to determine whether there was anything else they could do to market the drug for other users. That’s one of the big payoffs for these companies, that they market for one thing and then they find out it’s good for something else, so they make more in the by-product use than they do on the original. So, that’s why I came to Smith Kline. And while I was there of course they got me involved in other things.

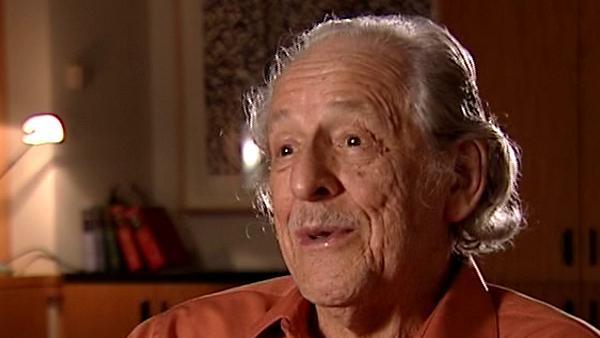

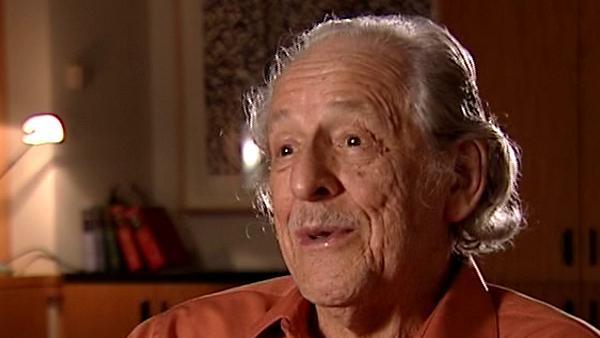

Eugene Garfield (1925-2017) was an American scientist and publisher. In 1960 Garfield set up the Institute for Scientific Information which produced, among many other things, the Science Citation Index and fulfilled his dream of a multidisciplinary citation index. The impact of this is incalculable: without Garfield’s pioneering work, the field of scientometrics would have a very different landscape, and the study of scholarly communication would be considerably poorer.

Title: Moving to Philadelphia to work for Smith, Kline & French

Listeners: Henry Small

Henry Small is currently serving part-time as a research scientist at Thomson Reuters. He was formerly the director of research services and chief scientist. He received a joint PhD in chemistry and the history of science from the University of Wisconsin. He began his career as a historian of science at the American Institute of Physics' Center for History and Philosophy of Physics where he served as interim director until joining ISI (now Thomson Reuters) in 1972. He has published over 100 papers and book chapters on topics in citation analysis and the mapping of science. Dr Small is a Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, an Honorary Fellow of the National Federation of Abstracting and Information Services, and past president of the International Society for Scientometrics and Infometrics. His current research interests include the use of co-citation contexts to understand the nature of inter-disciplinary versus intra-disciplinary science as revealed by science mapping.

Duration: 6 minutes, 56 seconds

Date story recorded: September 2007

Date story went live: 23 June 2009