NEXT STORY

Promoting Current Contents; the FASEB meeting in Atlantic City

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Promoting Current Contents; the FASEB meeting in Atlantic City

RELATED STORIES

It was evolved you know, first it was just titles and lists of compounds, and then later they added diagrams, and then we added the author’s abstracts, and then we added the indexing, because we also add... the most, the critical thing was the updating of the formula indexes, being able to retrieve... because you know what I recognised, found out when I was still at Welch Project, people did not use the name of a compound to find it; they never searched that way. They might sometimes, but the main way people found compounds was to go in by molecular formula, you know, the empirical formula, and then they would see the list of compounds that were isomers of that empirical formula and that was how you found the literature; you didn’t try to name it first, because 50% of the time you wouldn’t think of the right name anyhow. You had to have a special knowledge to be able to name the compounds with the system. So, that’s how I realised that the molecular formula was the key to retrieval rather than the name. So, to this day I think CA still regenerate the structural diagrams, and from there they name them according to the rules they create. The molecular formula is a by-product. And they can do all sorts of things automatically now which couldn’t be done back then. But I always say that’s a good case of one of my least cited papers having the highest economic impact on, on, you know, science. It was the algorithm for translating chemical formulas into... I mean chemical names into formulas, that had... that is the heart of searching chemical compounds these days, but very few people are writing papers about it and citing that algorithm. Which, you know, I not only had my thesis, but I published it as a paper in... well, first it was a brief, I had a brief half-page letter to the editor of Nature about my algorithm, it was called Chemical... Automatic Translation of Chemical Formulas. When I published that paper in Nature, that letter, I was taking a calculated risk that, in order for us to establish priority, that they wouldn’t prevent me from getting my degree. Because technically speaking, in those days, if you had published on it you couldn’t get your doctorate, you couldn’t use it as your dissertation any more. So, I published it but I knew that my dissertation advisor or nobody else would ever read Nature so nothing ever happened. So, that’s the original reference, that paper in Nature. And then the dissertation is the other reference on it. And then, I think, later on I wrote another paper in the journal Chemical about it. But a lot of people forget that even my 1951 paper about SCI, about the citation index, that’s not my most cited paper; the one that came later, in '72, I think it is...

[Q] Oh, you mean the '55 paper?

Yes, the '55 paper is not my most cited. You’d think that. It’s because of the journal evaluation thing and the impact factor that... and of course the book is cited a lot. The thing I find amusing about the book is that it doesn’t... people still cite chapter, chapter... Tibor Brown was desperate, I think, for articles for his new journal in the first year at Scientometrics, so he asked me if he could publish I think chapter 10 of my book as a paper. And that paper gets cited... it’s one of the most cited papers in Scientometrics. But nobody... they don’t seem to realise that it’s a chapter from the book, even though I think it says it, but it still gets cited separately. You have to count that in. The book is probably cited more than any of my papers, I don't know how many times.

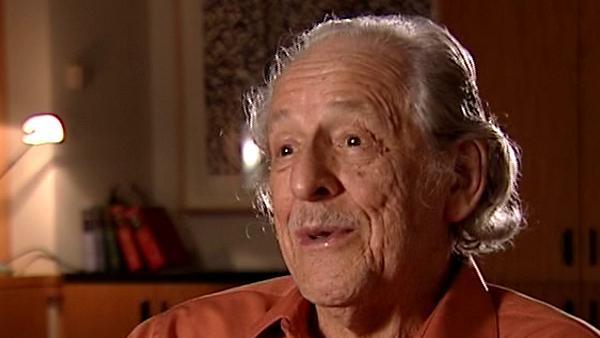

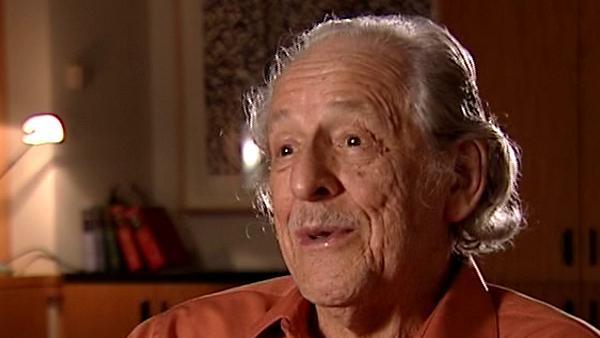

Eugene Garfield (1925-2017) was an American scientist and publisher. In 1960 Garfield set up the Institute for Scientific Information which produced, among many other things, the Science Citation Index and fulfilled his dream of a multidisciplinary citation index. The impact of this is incalculable: without Garfield’s pioneering work, the field of scientometrics would have a very different landscape, and the study of scholarly communication would be considerably poorer.

Title: Using molecular formula for retrieval and citations of my work

Listeners: Henry Small

Henry Small is currently serving part-time as a research scientist at Thomson Reuters. He was formerly the director of research services and chief scientist. He received a joint PhD in chemistry and the history of science from the University of Wisconsin. He began his career as a historian of science at the American Institute of Physics' Center for History and Philosophy of Physics where he served as interim director until joining ISI (now Thomson Reuters) in 1972. He has published over 100 papers and book chapters on topics in citation analysis and the mapping of science. Dr Small is a Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, an Honorary Fellow of the National Federation of Abstracting and Information Services, and past president of the International Society for Scientometrics and Infometrics. His current research interests include the use of co-citation contexts to understand the nature of inter-disciplinary versus intra-disciplinary science as revealed by science mapping.

Duration: 5 minutes, 22 seconds

Date story recorded: September 2007

Date story went live: 23 June 2009