NEXT STORY

Eastern European readership

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Eastern European readership

RELATED STORIES

I met him in... I went to Kiev at one point. You know he died because of the... Chernobyl. He died of cancer. He was out taking a... he was in Kiev, but he was apparently taking a sun bath or something like that, and they had not told anybody about the explosion, the meltdown, and a lot of people died of exposure to radiation that could have protected themselves if they’d known. I never got the full details, but that’s what I found out later, because I don’t know who found out for me or told me, but my friend... have you met Victor Vaskovsky? Do you remember when I went on a tour on the Trans-Siberian railroad with him? Well he was born in Kiev, so he goes back... he had gone back to Kiev. I’m sure he knew about Dobrov. So, that was a tragic outcome of that. He would have been a brilliant contributor; he was smart, Dobrov. He had...

[Q] Did you ever run across Mulchenko?

I don’t know. That’s the guy who wrote... whose co-author was Nalimov. Did you meet him?

[Q] No.

I don’t know who that person was. I never did meet him.

[Q] He was a politico or something.

I imagine we could ask Valentina, she probably knows who it is, or Jeanna, his wife. I still have contact with Nalimov’s wife. It was in the... it wasn’t until, I think, '65 when we went back to Moscow, we had exhibits at the Moscow book fair in order to promote sales in Russia, which didn’t turn out to be all that productive. The Russians had their system of controlled distribution, and they, they were not going to ever buy more than three or four copies of the SCI, come hell or high water. And the guy who made that decision, his name was Aritunov, and we knew him because, I forget what the occasion was that brought the Russian delegation to the US, and they all came to visit ISI, and in fact I had that whole group of Russians came out to my house in Swarthmore, and it was a snowy night, and because of the snow... we couldn’t get a car to take away, we had to march them through the Swarthmore campus to the train station to get them back into Philadelphia. I don’t know if those people knew they had all these Russians trampling all over the place, but Aritunov had been, spoke very good English, and had been a member of the Russian trade delegation during the war. So, he knew America very well. And he controlled, he made the decisions of how many copies of any journal were bought in the entire Soviet Union, scientific stuff. And I remember there was a library subscription at the Lenin Library, at the Moscow, what do they call it, the Moscow Public Library, and a third one at some other place in Moscow. And then later on there was an exception made... the library of the Academy of Sciences, was another one, and then Victor Vaskovsky got, he was secretary of the far eastern branch of the Academy, got some kind of special kind of dispensation to buy the SCI for their far eastern branch. That’s why, when he wrote to us, we put him on the board, the editorial board. And eventually he... he set up this tour. He took me on a tour to give a lecture about the SCI, the story, in Moscow, we went to Novosibirsk, and then we went to all these other places on the Trans-Siberian railroad. It was very fine. That is how I got to meet Pudovkin, he worked at the same place that Viktor did, at the Marine Biology Institute of Vladivostok. And when we got to Vladivostok I actually didn’t go into Vladivostok, because Americans couldn’t enter Vladivostok; you could go to the airport or they had a separate station, about 60 miles north of Vladivostok, I forget the name of it... Nahodka was a special place where all foreign people were taken, and then from Nahodka you could take a boat out of there to Japan. But you could not go into Vladivostok per se. You might... I don’t know if you could fly in there. They once took me to the airport, where I conducted a seminar at the airport actually. Later on... because you know what the reason was, we wouldn’t let the Russians in San Diego, so it was a reciprocal thing. But even Russians couldn’t go to Vladivostok; you had to have a special passport to get there even if you were Russian. It was like a secret city. The Russians are totally paranoid. I mean, everything they do has got to be veiled in secrecy, it’s just incredible. And they are used to it, and it’s amazing to accommodate to that. But it’s a little like the way of being with, having just visited Oak Ridge thinking about the Manhattan Project, can you imagine that town, what it was like. They’ve got a museum where they show some of that stuff now, it’s quite interesting. Amazing what was going on and nobody knew what the hell was going on. Very few people knew they were building a bomb. It’s incredible when you think of how many people worked on it.

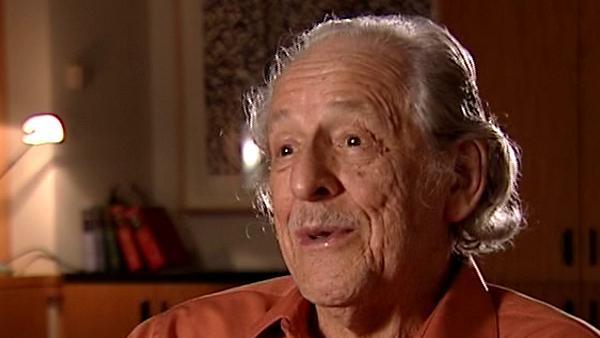

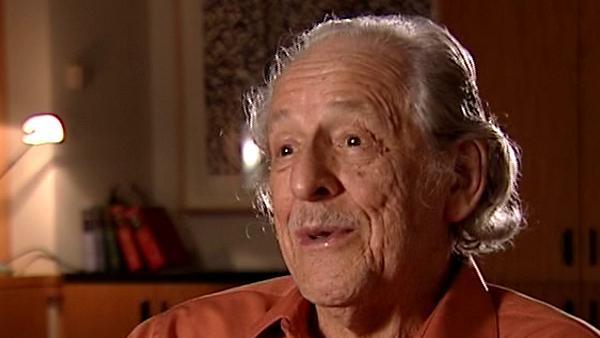

Eugene Garfield (1925-2017) was an American scientist and publisher. In 1960 Garfield set up the Institute for Scientific Information which produced, among many other things, the Science Citation Index and fulfilled his dream of a multidisciplinary citation index. The impact of this is incalculable: without Garfield’s pioneering work, the field of scientometrics would have a very different landscape, and the study of scholarly communication would be considerably poorer.

Title: Russian colleagues and travelling on the Trans-Siberian Railway

Listeners: Henry Small

Henry Small is currently serving part-time as a research scientist at Thomson Reuters. He was formerly the director of research services and chief scientist. He received a joint PhD in chemistry and the history of science from the University of Wisconsin. He began his career as a historian of science at the American Institute of Physics' Center for History and Philosophy of Physics where he served as interim director until joining ISI (now Thomson Reuters) in 1972. He has published over 100 papers and book chapters on topics in citation analysis and the mapping of science. Dr Small is a Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, an Honorary Fellow of the National Federation of Abstracting and Information Services, and past president of the International Society for Scientometrics and Infometrics. His current research interests include the use of co-citation contexts to understand the nature of inter-disciplinary versus intra-disciplinary science as revealed by science mapping.

Duration: 6 minutes, 54 seconds

Date story recorded: September 2007

Date story went live: 23 June 2009