NEXT STORY

Citing in patents and papers

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Citing in patents and papers

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 61. A job offer and teaching at the University of Pennsylvania | 41 | 03:06 | |

| 62. Sharing information and encyclopedists | 47 | 04:43 | |

| 63. The Atlas of Science | 46 | 02:59 | |

| 64. The Atlas of Science as a dynamic projection | 36 | 02:02 | |

| 65. Algorithmic and historiographic analysis | 37 | 06:38 | |

| 66. The future of open access and retractions in citations | 49 | 05:02 | |

| 67. Duplication in research and a citator for patents | 33 | 04:40 | |

| 68. Citing in patents and papers | 46 | 05:52 | |

| 69. Errors and how they affect retreival | 34 | 03:01 | |

| 70. The mathematics in papers today | 53 | 01:31 |

They did a study at ASLIB in the UK, back in the ‘60s, and established that, they made an estimate that 25% of researchers reported that... researchers reported that 25% of their work was unwitting duplication. Now, I had to go back and find out what the definition of that was, but this came up last week, in the USA, is that true anymore? To what extent is research unwittingly duplicated today? I don’t know. If you go on the Mertonian principle that all the simultaneous discoveries that go on, it’s some sort of an axiomatic thing. I don’t know to what extent, but I would think that it would be less unwitting duplication today; there might be a lot of deliberate, more deliberate duplication. And the question is, if it’s deliberate, is it moral if they don’t cite what they know already exists? Now, if you’re applying for a patent, then you know that it, previously that you’ve actually violated the law, you know. When you’ve signed your application, you’ve got to, you’re testifying the fact that you think that this is original, and you’ve done your research. But I have always said that it ought to be a matter of... a standard of procedure ought to be that when people publish, or apply, for patents, that they should certify what they have done in the way of verifying that this is an original piece of work, you know. Now, the way things work today, sometimes you could find out if something was reported before easier, by just going up on some bulletin board, if you’re willing to expose your idea. But, you know, you take a chance. If you say, is this an original idea, then somebody else grabs it! Well, it’s tough. But if you’re just trying to establish whether something ever was done before... I’m always amazed at how quickly people give the answers to, do you? You know, that, like that Chem Info website... it’s amazing how quick I get answers on some of that stuff. And on the other hand, people are always willing to say there’s plenty of examples of research that’s duplicated. When I applied for a patent on HistCite, I got the patent, but when the application was filed in Europe, the same identical application, one of the examiners cited one of my papers against me! I thought that was the ultimate irony. But that was because they didn’t really understand the concept, you know. Not totally without rationale, that, to say, well, you talked about something like that 30 or 40 years ago; that’s not the same thing as saying, actually, solve the problem. Right? So, that was a crazy kind of thing that the... tt was one of the earliest subjects that we... patents were one of the earliest things that we studied in the way of the citation, the value of citation indexing. And back in the early days, I actually published one of my first papers, was published in a journal at the Patent Office Society. And even before that paper, which was about 1956, I think, Arthur Seidel – did you ever meet my friend, Arthur Seidel? – who’s still practising law, by the way, he still goes in. He’s now moved to a retirement community, but he’s still - because his wife was tired of taking care of the house – he still goes into the office. He’s, he’s an incredible guy. He’s a walking encyclopaedia. And, he published a letter in the journal of the Patent Office Society in 1949, on the idea of doing a citator for patents. And, of course, the patent office never did anything about it at that time. But that’s how old the idea is. And I think that I picked up that letter of his and cited it in my paper later.

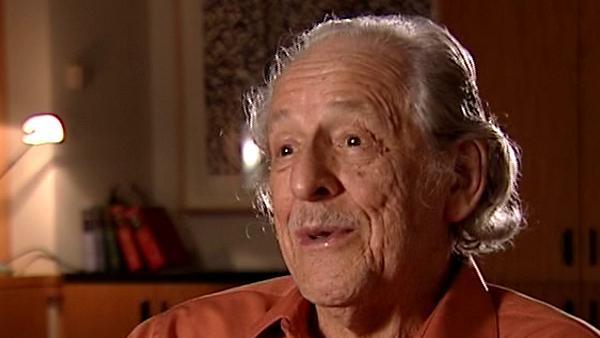

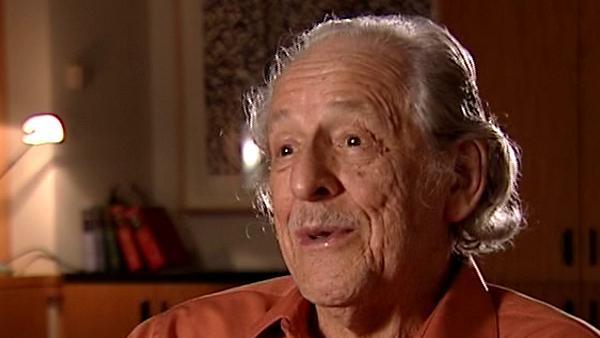

Eugene Garfield (1925-2017) was an American scientist and publisher. In 1960 Garfield set up the Institute for Scientific Information which produced, among many other things, the Science Citation Index and fulfilled his dream of a multidisciplinary citation index. The impact of this is incalculable: without Garfield’s pioneering work, the field of scientometrics would have a very different landscape, and the study of scholarly communication would be considerably poorer.

Title: Duplication in research and a citator for patents

Listeners: Henry Small

Henry Small is currently serving part-time as a research scientist at Thomson Reuters. He was formerly the director of research services and chief scientist. He received a joint PhD in chemistry and the history of science from the University of Wisconsin. He began his career as a historian of science at the American Institute of Physics' Center for History and Philosophy of Physics where he served as interim director until joining ISI (now Thomson Reuters) in 1972. He has published over 100 papers and book chapters on topics in citation analysis and the mapping of science. Dr Small is a Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, an Honorary Fellow of the National Federation of Abstracting and Information Services, and past president of the International Society for Scientometrics and Infometrics. His current research interests include the use of co-citation contexts to understand the nature of inter-disciplinary versus intra-disciplinary science as revealed by science mapping.

Duration: 4 minutes, 40 seconds

Date story recorded: September 2007

Date story went live: 23 June 2009