NEXT STORY

Early life and school

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Early life and school

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 71. Unusual applications for the Lewis and Clark Fund | 51 | 05:04 | |

| 72. Other activities of The American Philosophical Society | 25 | 04:01 | |

| 73. A meeting in Japan and the 40th anniversary of my first paper | 32 | 03:02 | |

| 74. Taking medication prophylactically | 41 | 04:23 | |

| 75. The pros and cons of individualized patient therapy | 33 | 03:17 | |

| 76. What if... the future of epidemiology? | 44 | 04:48 | |

| 77. Development of ancillary technologies | 45 | 07:01 | |

| 78. Identifying disease carriers - a double-edged sword? | 36 | 04:10 | |

| 79. The Daedalus Factor | 67 | 07:08 | |

| 80. Expect the unexpected | 67 | 03:00 |

I think it's an important lesson in science, not to expect perfection. And it's actually, it's really important to know that, because that means something is going to happen that you don't know what it is. Well, how can you… how can you… something unexpected is going to happen. So how can you expect the unexpected? When are you going to expect that something unexpected is going to, so you're kind of prepared? Well, the best way to be prepared is to not try to get narrow answers, you know, get yes/no answers. But you want to kind of look around the issue. You want to see the stuff that doesn't seem so important - it's not goal-directed. You know, if you have a goal, you don't want to... when I was working on this therapy, you know, for the virus, and we were funded by some drug companies, they didn't want us to go off on tangents, that, you know, that we think, gee, well, it doesn't have to do with the manufacture of the drug; this is pretty interesting stuff. They want you to, you know, they have land… what do they call them? Not landmarks, but…

[Q] Milestones.

Milestones, yeah. And they have, somebody's got them at an office in some top level of the drug company, and you have to sort of check in on the milestones so often. And if you hit the milestones, the stock goes up, you know, and if you don't hit the milestones, the Wall Street guys find out about it, and the stock goes down. So there's a lot wrapped up in not looking at extraneous stuff. Which, I think, in the long run is not a good idea, because actually you miss... because the history of science is, you always find stuff that you hadn't expected. That was certainly, you know, that's my personal experience. We weren't looking for a hepatitis virus, but we were prepared for the unexpected.

That's another Heraclitean... you know, Heraclitus, the 3rd, 4th Century BC Greek philosopher, I suppose. And he said you… you have to expect the unexpected, because it's fleeting. He's the same fellow who said, the same philosopher who said, you can't step twice into the same stream, you know, because it's always changing. Everything's in flux; you never can do the same experiment twice. And experimental science has tried to get around that by… by putting a cork in the test tube, you know, you put item A into item B; chemical A, chemical B. There's a cork in the test tube, so nothing outside gets in, then you look and see what results. But the cork's not tested, you know, there is no cork in the… in the world. So you'll always have this interference. I'm not arguing against that, because it's the development of experimental science that actually has brought us to where we are now, but there are limitations to it. It's not… it’s not always the… always the answer.

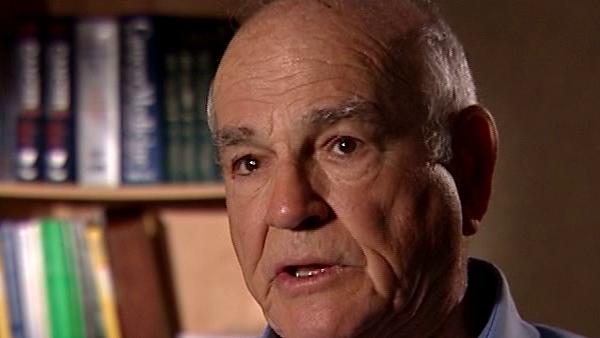

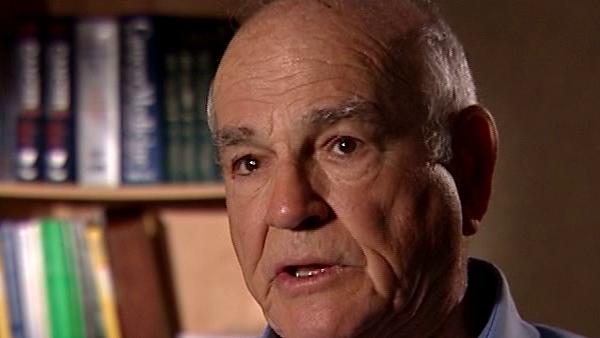

American research physician Baruch Blumberg (1925-2011) was co-recipient of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1976 along with D Carleton Gajdusek for their work on the origins and spread of infectious viral diseases that led to the discovery of the hepatitis B virus. Blumberg’s work covered many areas including clinical research, epidemiology, virology, genetics and anthropology.

Title: Expect the unexpected

Listeners: Rebecca Blanchard

Dr Rebecca Blanchard is Director of Clinical Pharmacology at Merck & Co., Inc. in Upper Gwynedd, Pennsylvania. Her education includes a BSc in Pharmacy from Albany College of Pharmacy and a PhD in Pharmaceutical Chemistry from the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. While at Utah, she studied in the laboratories of Dr Raymond Galinsky and Dr Michael Franklin with an emphasis on drug metabolism pathways. After receiving her PhD, Dr Blanchard completed postdoctoral studies with Dr Richard Weinshilboum at the Mayo Clinic with a focus on human pharmacogenetics. While at Mayo, she cloned the human sulfotransferase gene SULT1A1 and identified and functionally characterized common genetic polymorphisms in the SULT1A1 gene. From 1998 to 2004 Dr Blanchard was an Assistant Professor at Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia. In 2005 she joined the Clinical Pharmacology Department at Merck & Co., Inc. where her work today continues in the early and late development of several novel drugs. At Merck, she has contributed as Clinical Pharmacology Representative on CGRP, Renin, Losartan, Lurasidone and TRPV1 programs and serves as chair of the TRPV1 development team. Dr Blanchard is also Co-chair of the Neurology Pharmacogenomics Working Group at Merck. Nationally, she has served the American Society of Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics on the Strategic Task Force and the Board of Directors. Dr Blanchard has also served on NIH study sections, and several Foundation Scientific Advisory Boards.

Tags: Heraclitus

Duration: 3 minutes

Date story recorded: September 2007

Date story went live: 28 September 2009