NEXT STORY

Testing the Marshall Islanders for Australia antigen

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Testing the Marshall Islanders for Australia antigen

RELATED STORIES

We found this antigen in an Australian and... and that react with an antibody in a hemophilia patient from New York City so the question is what it was and we decided the next step is do another inductive stage, that is, collect more data and sort of make hypotheses based on that. So we did, we indentified the Down syndrome patients in the way that I told you before, looking at people that are high risk of leukemia, and then we were able to observe these patients and others, and one of the things we discovered was that there was a… there was a consistent characteristic. If the… if the individual had Australia antigen, as we called it, on the first test and you tested them two months later or three months, a year later, they still had it so it seemed to be a persistent characteristic which is what you would expect of… of a phenotype of… of an expression of a gene, that it stayed more or less consistent. But then we found an exception to that in one of the Down syndrome patients who we'd been caring for here at Fox Chase Cancer Center and taking and examining his blood every month or so. Initially when we first saw him, he did not have the antigen and then he subsequently developed it. Well, the question is what had happened? Well, we were able to… we looked at a whole bunch of characteristics, you know, physiological, pathological tests that could be done and what we found is that between the time we detected the Australia antigen and… and the time that it had not been present, that he had developed a form of hepatitis and it wasn't… he didn't have symptoms but there were changes in his chemistry, in his liver, that measured liver function, that indicated that he had had a very mild — as a matter of fact imperceptible to the person — but it was definitely hepatitis. Well, that observation sort of generated the hypothesis that the Australia antigen was associated with hepatitis. And then we went on to test that hypothesis by collecting blood from people who had hepatitis and then from controls, people who didn't have hepatitis and we did this in a variety of ways, and in each case, the hypothesis was not rejected: we found a higher prevalence. And that… then we made the next hypothesis, that the Australia antigen was part of the virus and the paper that we published that information came out 40 years ago, just about this time it was published.

[Q] Were there forms of the... were there specific patients with hepatitis that didn't have the antigen? Were you able to differentiate among hepatitis forms?

Yes. Not every person with hepatitis reacted, but it was already known, prior to our work, that there were at least two kinds of hepatitis. We now know there're probably half a dozen, but three or four common ones, and so it was not surprising that they didn't all have it but we thought we'd recognize one form and, based on the prior kind of theoretical nomenclature, this one, what had been referred to as hepatitis B, and so, and that's the kind that's transferred by blood, by transfusion or needle injection and as we now know, by transmissions. But, so that observation we made on our patient here, that's what stuck in our mind as being the clue that made us test the hypothesis, but actually we had some other clues prior to that.

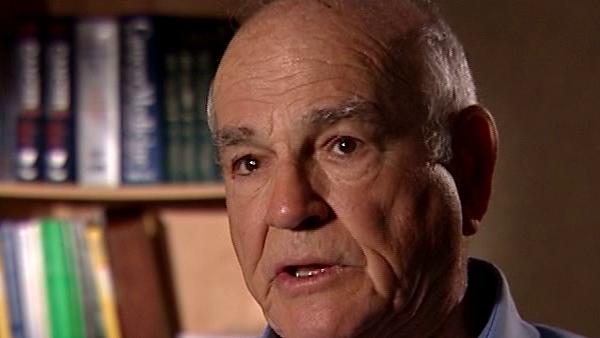

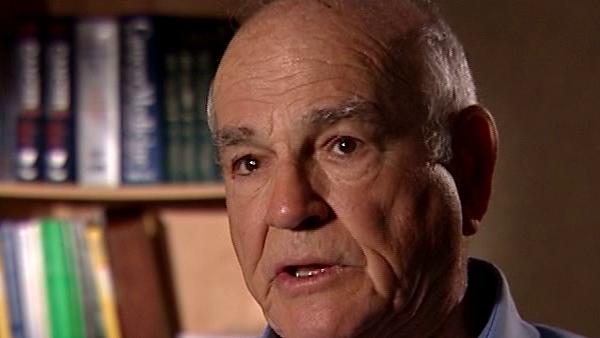

American research physician Baruch Blumberg (1925-2011) was co-recipient of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1976 along with D Carleton Gajdusek for their work on the origins and spread of infectious viral diseases that led to the discovery of the hepatitis B virus. Blumberg’s work covered many areas including clinical research, epidemiology, virology, genetics and anthropology.

Title: Is there a link between Australia antigen and hepatitis?

Listeners: Rebecca Blanchard

Dr Rebecca Blanchard is Director of Clinical Pharmacology at Merck & Co., Inc. in Upper Gwynedd, Pennsylvania. Her education includes a BSc in Pharmacy from Albany College of Pharmacy and a PhD in Pharmaceutical Chemistry from the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. While at Utah, she studied in the laboratories of Dr Raymond Galinsky and Dr Michael Franklin with an emphasis on drug metabolism pathways. After receiving her PhD, Dr Blanchard completed postdoctoral studies with Dr Richard Weinshilboum at the Mayo Clinic with a focus on human pharmacogenetics. While at Mayo, she cloned the human sulfotransferase gene SULT1A1 and identified and functionally characterized common genetic polymorphisms in the SULT1A1 gene. From 1998 to 2004 Dr Blanchard was an Assistant Professor at Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia. In 2005 she joined the Clinical Pharmacology Department at Merck & Co., Inc. where her work today continues in the early and late development of several novel drugs. At Merck, she has contributed as Clinical Pharmacology Representative on CGRP, Renin, Losartan, Lurasidone and TRPV1 programs and serves as chair of the TRPV1 development team. Dr Blanchard is also Co-chair of the Neurology Pharmacogenomics Working Group at Merck. Nationally, she has served the American Society of Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics on the Strategic Task Force and the Board of Directors. Dr Blanchard has also served on NIH study sections, and several Foundation Scientific Advisory Boards.

Tags: Australia antigen, pateitns, phenotype, blood, hepatitis, virus, hypothesis

Duration: 4 minutes, 4 seconds

Date story recorded: September 2007

Date story went live: 28 September 2009