NEXT STORY

Studying behavior and genetics as an undergraduate

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Studying behavior and genetics as an undergraduate

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11. Reading the Great Books | 206 | 05:34 | |

| 12. Studying behavior and genetics as an undergraduate | 2 | 184 | 05:01 |

| 13. Deciding to be a scientist | 181 | 07:56 | |

| 14. Going to Indiana University | 134 | 06:31 | |

| 15. Courses at Indiana and my thoughts on philosophy | 123 | 05:30 | |

| 16. 'The function of Chicago was to prepare you for greatness' | 149 | 06:21 | |

| 17. Salvador Luria and how Indiana University reacted to his bluntness | 184 | 03:41 | |

| 18. My PhD period with the phage group | 150 | 09:16 | |

| 19. Switching to nucleic acid chemistry and moving to Copenhagen | 114 | 05:16 | |

| 20. Going to Cambridge | 161 | 09:07 |

So we did read the great books, but we also read a book called a textbook, it was the only textbook I remember from Chicago, called, Main Currents in American Thought by Vernon Parrington who was a professor in Seattle, the University of Washington. It was a leftist book on the whole, you know, it was very much an economic interpretation of American History. But Charles Beard at Columbia had written a book called the Economic Interpretation of the Constitution. So, you know, it was... economics played a role and so I was very pleased that, you know, if we just read Lincoln's addresses and all that, an intellectual text, which was concerned with why things happened as opposed to what happened. It was a very good counter-balance to...

[Q] The history of ideas.

History of ideas. And then the striking thing about Chicago was that the... you only had one exam a year, at the end of the course. You had practice exams, so you were taking exams at, sort of, know where you were but it didn't count, it would never go on your transcript. And half the questions they were all multiple-choice, so they could be graded by... there was already some automatic thing, so where they would give you a question and there were five possible answers and at least two of them seemed plausible. So, I think, in many cases it was arbitrary which one you chose, but they all involved trying to interpret facts, so you would be given a paragraph on history and then these questions, so you would have to interpret it. So it was all toward reasoning – the whole point of the Chicago education was to reason from... draw a conclusion from a paragraph. And that's how you were judged.

[Q] So now did your habit of not taking notes during lectures and so on come from that era?

Possibly, because there was no point.

[Q] There was no point.

In the college, you wouldn't take a note, they were there for fun. Then, when I started taking some science courses, I remember everyone was writing down what they said, and I didn't. And the embryologist, Paul Weiss, developed an extreme dislike of me because I was someone who was not writing down what he was saying, and he afterwards sort of told me that he was very annoyed when I got an A in the exam. You know, that I would look at other people's notes or something and there was a textbook, and you know, it was pretty... it was basically zoology or it was taxonomy.

[Q] So how did the science? How did you get interested in science? Was it at the University of Chicago or had you already had it before you went there?

No, I think, it was because of birds. And birds... there was the beginning of the study of animal behavior– Lorenz and Tinbergen. So they were probably going on roughly the same time I was being educated and the... so, it was, you know, totally about instinct pretty early on and, you know, and instinct probably had to go back to genes. So the concept that behavior was controlled, or could be controlled by genes, I would have just taken for granted by 1946. You know, the belief I've had ever since that and then of course you were told that humans were different, you know, that we had evolved so... but of course, in those days it was just behavior. You never thought of how you would behave in... whether you were related or whether you had too much dopamine or serotonin or norepinephrine, so those were much later things. So, you know, it was just behavior.

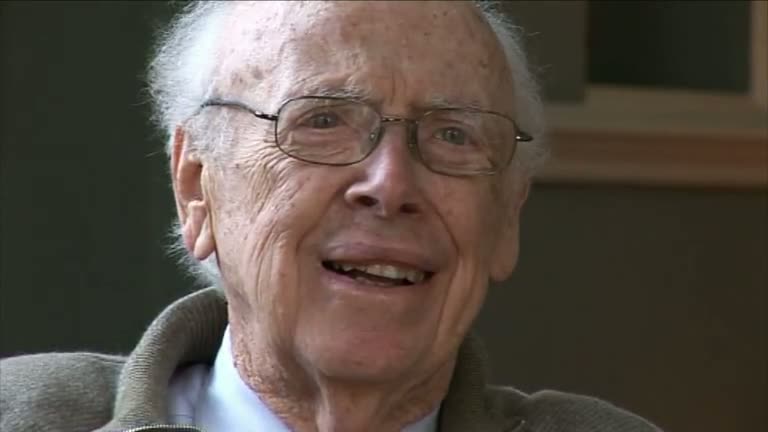

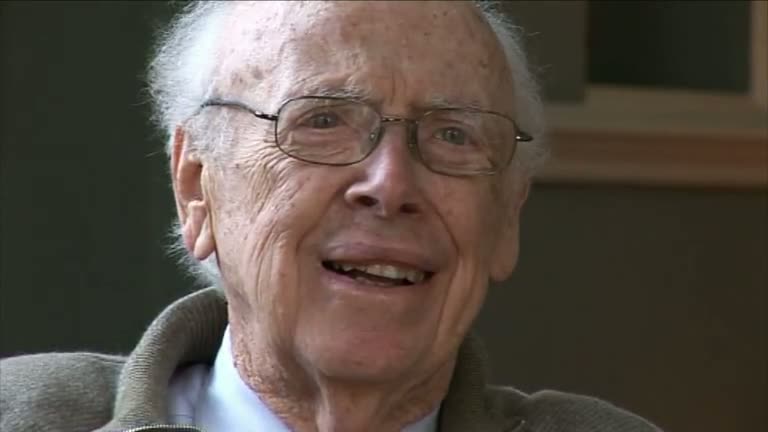

American molecular biologist James Dewey Watson was best known for discovering the structure of DNA for which he was jointly awarded the 1962 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine along with Francis Crick and Maurice Wilkins. His long career saw him teaching at Harvard and Caltech, and taking over the directorship of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York. From 1988 to 1992, James Watson was head of the Human Genome Project at the National Institutes of Health.

Title: Reading the Great Books

Listeners: Martin Raff Walter Gratzer

Martin Raff is a Canadian-born neurologist and research biologist who has made important contributions to immunology and cell development. He has a special interest in apoptosis, the phenomenon of cell death.

Walter Gratzer is Emeritus Professor of Biophysical Chemistry at King's College London, and was for most of his research career a member of the scientific staff of the Medical Research Council. He is the author of several books on popular science. He was a Postdoctoral Fellow at Harvard and has known Jim Watson since that time

Tags: Main Currents in American Thought, Economic Interpretation of the Constitution, University of Chicago, Paul Weiss

Duration: 5 minutes, 34 seconds

Date story recorded: November 2008 and October 2009

Date story went live: 18 June 2010