NEXT STORY

'If you don't like mathematics, don't give up'

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

'If you don't like mathematics, don't give up'

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. I never grew out of my bug period | 6 | 657 | 05:04 |

| 2. 'If you don't like mathematics, don't give up' | 2 | 839 | 02:59 |

| 3. A grand tour with Thomas Eisner | 1 | 296 | 05:23 |

| 4. Eating a big green katydid | 78 | 02:57 | |

| 5. Discovering ant colonies | 218 | 05:05 | |

| 6. Why I study ants | 362 | 01:09 | |

| 7. The Ants | 249 | 03:05 | |

| 8. Our book receives the Pulitzer Prize | 1 | 231 | 02:18 |

| 9. Fieldwork is exhilarating | 196 | 03:07 | |

| 10. The truly grand experience of my career | 207 | 06:09 |

Every kid has a bug period. I had mine. I just never grew out of mine. Somehow I stayed with it. And I found no greater joy when I was about nine or ten years old than collecting spiders and ants and especially butterflies. I began actually when I lived in Washington DC, our nation's capital for two years. Although a southerner, I'd come up there because my father was a federal employee and after two years we went back down to the home town of Mobile, Alabama. And in Washington I came up with a real interest in animals because our apartment was within walking distance of the national zoo, which is a wonderland for a kid... free, wander through there any time you want.

I was a trolley ride from the US National Museum of Natural History, one of the great museums in the world. And it was a paradise. I spent time collecting insects and then going over and looking at them in the museum, and imagining what it must be like to be in Arthur Conan Doyle's lost world while I was in the zoo. Then I also spent a lot of time wandering around a park called Rock Creek Park, that winds all around the zoo. That was my equivalent of a wilderness when I was a little kid. And so I guess by the time I was ready to go back to Mobile, and then encounter a sub-tropical fauna butterfly species that are found only in the warm, temperate... very warm temperate or sub-tropical [inaudible] occurring there, which didn't occur in Washington, and the great, much greater diversity of plants and animals, many of them not well-studied... I guess by that time I would have thought it odd that anybody would want to be anything else but an entomologist or at least a naturalist, a biologist.

Actually, I became an entomologist instead of a specialist on something else like birds because I was, and am, handicapped. When I was a kid, still before we went to Washington at the age of seven, I was in a military academy. All real southerners want to put their kids in the military academy, or at least they did in the '30s. That was a southern tradition. The highest one could aspire to was West Point or the Naval Academy and have a son in the peace time or war time, an officer in the armed services. And those two academies were tough places, but in any case, about that time I spent a summer in a place called Paradise Beach. I spent all my time fishing. I guess I was about seven years old. And one day I pulled up what's called a pinfish. These are fish with needle-like spines in the dorsal fin. One of them got me in the eye. And that resulted in a traumatic cataract. I didn't even tell anybody about the excruciating pain because I was afraid they might stop me from fishing. But later when I only had vision in one eye, I discovered as all true naturalists do, when I began trying to study birds, you've got to go through your Roger Tory Peterson stage with field guides and look at birds if you're going to be a real naturalist some time in your teens. And I discovered that I was a lousy birdwatcher, partly because of my vision. And you know, I couldn't see them. You can't judge distance very well.

Furthermore, I also have a condition where I don't hear the upper registers very well. So I couldn't hear them, I couldn't spot them, how was I going to be a halfway decent ornithologist if I...? I just loved insects anyway, so I decided that, at about the age of 16, that I was going to be an entomologist. And I was so dedicated to it that even though I never really got a very good background in the school systems of Alabama, in mathematics or physics or chemistry, my interest in the background I'd built up in natural history propelled me right on through to the Harvard graduate school and then quickly a post-doctoral fellowship in Harvard's society of fellows which gave me three years of completely free and fully supported research.

I want to emphasise one thing, and then another. And the one thing is to be a successful scientist you need to do what you like to do. If you don't like mathematics, don't give up. That doesn't forestall your being a scientist at all. Because I have, at best, average mathematical ability, it comes hard to me. And if you really don't have a taste for laboratory work, white coat, experiments, measuring, and so on, and a lot of very promising scientists do not have a taste to be an experimental scientist, don't worry about it.

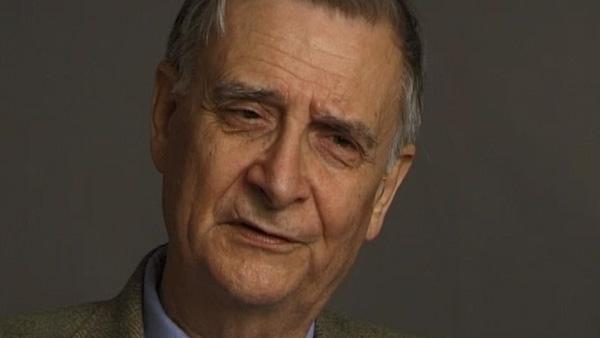

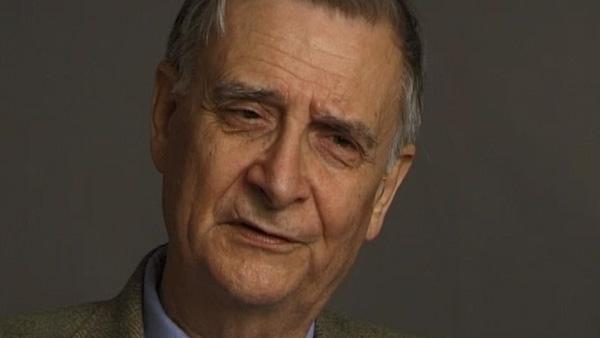

EO Wilson (1929-2021) was an American biologist, researcher (sociobiology, biodiversity), theorist (consilience, biophilia), naturalist (conservationist) and author (two Pulitzer Prizes). His biological specialty was myrmecology, the study of ants.

Title: I never grew out of my bug period

Listeners: Christopher Sykes

Christopher Sykes is a London-based television producer and director who has made a number of documentary films for BBC TV, Channel 4 and PBS.

Tags: The Smithsonian National Zoo, National Museum of Natural History, Rock Creek Park, Harvard University, The Harvard Society of Fellows, entomologist, naturalist, biologist, West Point, United States Naval Academy, pinfish, Arthur Ignatius Conan Doyle, Roger Tory Peterson

Duration: 5 minutes, 5 seconds

Date story recorded: 2000

Date story went live: 22 May 2018