NEXT STORY

The government's attitude towards India's art

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

The government's attitude towards India's art

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 21. Organising an exhibition in Delhi | 54 | 09:28 | |

| 22. Working with Benode Bihari Mukherjee | 58 | 03:25 | |

| 23. Interest in Italian painting | 46 | 04:03 | |

| 24. Satyajit Ray | 92 | 02:36 | |

| 25. Leaving Santiniketan for Baroda | 42 | 01:51 | |

| 26. The partition of Indian and going to Baroda University | 39 | 04:11 | |

| 27. Life at Baroda | 58 | 04:06 | |

| 28. From Baroda to writing and the Slade School of Art, London | 48 | 02:52 | |

| 29. My wife, Susheela | 75 | 07:13 | |

| 30. London, language, tradition and the various influences on my art | 73 | 05:22 |

Did your subject matter change when you were in London, when you were away from India?

Not considerably, but to some extent, I suppose. I don’t really -because after seeing all those mediaeval things and various kinds of artefacts in the museums, I got interested in certain things which I wanted to do. I didn’t immediately start doing them, but then yes, sort of thing. So the experience did make an impact, but all these things I had already been thinking about earlier.

Do you think you had already achieved something as an artist even at that time, or do you feel that most of it is after that?

Well, concept-wise yes, but I knew that at that time that there were various things I wanted to do that I had to still get prepared with, and I was not too sure which direction I had to go. So it took me some time. I had already started working with various materials at that time, but then not to the extent I did later. I had already noticed from the museums that each kind of art object had its own kind of accent or linguistic accent, and artists can use them to their benefit, if they understand what they had to be done, and that is what I have been doing since, this sort of thing.

I hinted earlier that your language, your early language experience could have some effect on that thinking.

That’s right, true. It is quite true, and then this question of the various dialects in a sort of a whole tradition was in my mind even before I decided to be an artist. In fact, I was interested in what was happening in Santiniketan, even when I was studying economics. It was in the present library that I discovered Ananda Coomeraswamy and his Mediaeval Sinhalese Art. Probably it was a very polemical book and he wrote various things which I might not fully agree with, but the thesis he presented was very attractive to me, that when you are talking about, of course he was drawing Mediaeval Sinhalese Art but the art he was talking about was of the 17th and 18th Centuries. I mean, it is not mediaeval in that sense. So he was thinking of mediaeval as the site of the world which had that kind of spirit of inter-relationship. Then it started me thinking on certain lines. One thing, what is called tradition? Generally we think in terms of tradition in the kind of, let us say, in a sort of an upward line, or a downward line. It comes from one to the other in terms of various successions, but then there is in tradition a horizontal line where various kinds of activities reinforce each other and probably borrow from each other, or influence each other, and give each other a kind of personality composite. And you can see that in traditional India, or maybe in traditional Europe. So that was how art interested me from that time onwards. So when I came here and then I saw the various things in the European museums and came back, then I suddenly had a great desire to know about what is happening among the traditional artists and craftsmen. That is why soon after I came back from England I thought I should take a break, and the chance came quite readily. I mean, wanted me to work for them. I had an offer from the Antique Crafts Board, another from the Handloom Board, so I joined the Handloom Board for 2 years, and then went around and found that it was greatly educative, at least for me. I did an amount of work with the young people that were hired at that time and we became young friends and did something worthwhile, but I also learned in the process that to work within a government setup is very difficult and very frustrating, and whatever you did is almost brushed under the carpet, for the reason that certain kind of other agencies work to each one’s benefit and the government doesn’t sort of. So, after about 2 years of this educational break, I thought I would come back to Baroda, that’s how it came.

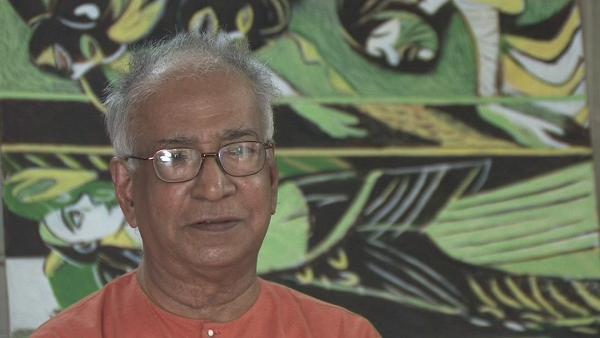

KG Subramanyan (1924-2016) was an Indian artist. A graduate of the renowned art college of Kala Bhavana in Santiniketan, Subramanyan was both a theoretician and an art historian whose writings formed the basis for the study of contemporary Indian art. His own work, which broke down the barrier between artist and artisan, was executed in a wide range of media and drew upon myth and tradition for its inspiration.

Title: London, language, tradition and the various influences on my art

Listeners: Timothy Hyman

Timothy Hyman is a graduate of Slade School of Fine Art, London, in which he has also taught. In 1980 and 1982, he was Visiting Professor in Baroda, India. Timothy Hyman has curated many significant art exhibitions and has published articles and monographs on both European and Indian artists.

Duration: 5 minutes, 22 seconds

Date story recorded: 2008

Date story went live: 10 September 2010