NEXT STORY

Public lectures

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Public lectures

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 101. Population growth | 71 | 04:00 | |

| 102. Only science can prevent the problems of population growth | 40 | 01:51 | |

| 103. Eigen's book: Treatise on Matter, Information, Life and... | 96 | 04:09 | |

| 104. Duties to society | 46 | 03:05 | |

| 105. The molecular biologist and the shepherd | 60 | 02:08 | |

| 106. Science in society | 39 | 04:13 | |

| 107. Public lectures | 44 | 02:34 | |

| 108. The winter seminars | 62 | 02:56 | |

| 109. Why the winter seminars are unique | 89 | 02:42 | |

| 110. Summing up: remembering co-workers and colleagues | 81 | 03:28 |

We are fortunately coming now to an age again where people think that the insight in science should really be made available to society via applications. There was a time where this was not so. For every new discovery they asked, 'What danger does it bring about?' They didn't ask what is the utility... the use, for mankind. Now, we made in our work on biotechnology... I mentioned already that evolution forms a basis, a principle, a new principle, for a new technology, which I call evolutionary technology in contrast to the classical biotechnology which is a conservative technology. What does it mean, conservative? It comes from the Latin word 'conservar', that means maintain. And as you see in the classical biotechnology, everything is maintained. You use a gene, let's say a human gene for insulin. You want to make insulin and you use it from human, so you have not invented this gene, nature has invented it. But you use it, you maintain it, you conserve it. And then you put this gene into a coli cell, via a plasmid and so. So you use the production machinery of nature, you don't change this machinery, nature has invented it, you conserve it and let it produce. So the only artificial thing you do is that you plant a human gene into a micro-organism which is better in producing the material and which you have to make sure that the micro-organism doesn't throw it away because it is of no use for the micro-organism, we want to use the insulin produced by it. But this is very important for... and there are many other processes now in pharmacology where you can produce most natural pharmaca in order... by this technology. And we, for change, call our technology an evolutionary technology. You don't have to conserve your gene, you let it evolve. You might start with a given gene and produce, but you don't have to produce it de novo. And you don't need a animal or a organism to produce what nature has produced, you built a machine which you invent and optimise for your purposes. And I think that the future in biotechnology certainly will be a combination of the two. And we thought we should introduce this into technology, and you yourself were involved too with some colleagues together with several scientists. Some years ago we founded the company Evotec in Hamburg. We were fortunate to find somebody to give the money for it and the company is developing quite well, has now eighty employees already and so this is also, as I considered, a service for society.

[Q] And it took over the people out of your evolution school, so to speak.

Yes, it gave them a job, which in our days is an important thing. There are many people which do not have a job. And it's even a job which could be a profession... where they can... their professionality... where they can use what they learnt.

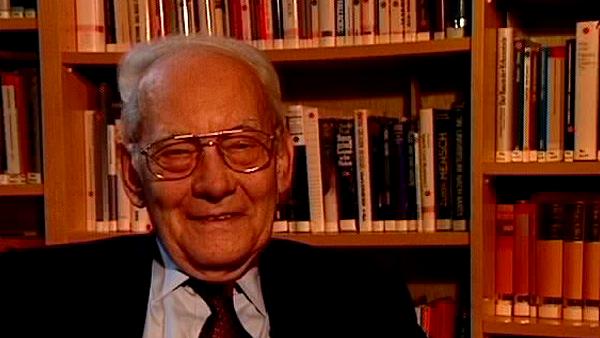

Nobel Prize winning German biophysical chemist, Manfred Eigen (1927-2019), was best known for his work on fast chemical reactions and his development of ways to accurately measure these reactions down to the nearest billionth of a second. He published over 100 papers with topics ranging from hydrogen bridges of nucleic acids to the storage of information in the central nervous system.

Title: Science in society

Listeners: Ruthild Winkler-Oswatitch

Ruthild Winkler-Oswatitsch is the eldest daughter of the Austrian physicist Klaus Osatitsch, an internationally renowned expert in gas dynamics, and his wife Hedwig Oswatitsch-Klabinus. She was born in the German university town of Göttingen where her father worked at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Aerodynamics under Ludwig Prandtl. After World War II she was educated in Stockholm, Sweden, where her father was then a research scientist and lecturer at the Royal Institute of Technology.

In 1961 Ruthild Winkler-Oswatitsch enrolled in Chemistry at the Technical University of Vienna where she received her PhD in 1969 with a dissertation on "Fast complex reactions of alkali ions with biological membrane carriers". The experimental work for her thesis was carried out at the Max Planck Institute for Physical Chemistry in Göttingen under Manfred Eigen.

From 1971 to the present Ruthild Winkler-Oswatitsch has been working as a research scientist at the Max Planck Institute in Göttingen in the Department of Chemical Kinetics which is headed by Manfred Eigen. Her interest was first focused on an application of relaxation techniques to the study of fast biological reactions. Thereafter, she engaged in theoretical studies on molecular evolution and developed game models for representing the underlying chemical proceses. Together with Manfred Eigen she wrote the widely noted book, "Laws of the Game" (Alfred A. Knopf Inc. 1981 and Princeton University Press, 1993). Her more recent studies were concerned with comparative sequence analysis of nucleic acids in order to find out the age of the genetic code and the time course of the early evolution of life. For the last decade she has been successfully establishing industrial applications in the field of evolutionary biotechnology.

Tags: conservar, biotechnology, evolutionary technology, Evotec AG, Hamburg

Duration: 4 minutes, 14 seconds

Date story recorded: July 1997

Date story went live: 29 September 2010