NEXT STORY

The box that attracted me to science

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

The box that attracted me to science

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11. The Gaia Theory | 1 | 523 | 05:52 |

| 12. My advice to young scientists | 3 | 645 | 05:17 |

| 13. Question the dogma! | 330 | 06:15 | |

| 14. Measuring the atmosphere | 201 | 04:54 | |

| 15. Why I am a green sceptic | 3 | 1046 | 02:36 |

| 16. Green politics: pesticides | 2 | 290 | 03:00 |

| 17. What I've learned from my life in science | 1 | 339 | 04:34 |

My life as scientist has taught me several things about science and one of the most important and least realised is the uncertainty of science. No scientist can be certain about anything and yet people want certainty. And that's why science can in no way ever replace or supplant religion. People need certainties in their lives, they need to believe in things and science can never offer them that.

And one of the problems with science nowadays, it's drifting more and more into fiction and legend, and farther and farther. Most people's views of science come from programmes like Star Trek. They see it, that as the reality and not, and there's an awful lot of certainty in that kind of reality, which is not present in the real scientist's view of the world. It's a matter of knowledge. What… I've thought a lot about this and one of the things that a politian, President Havel of the Czech Republic, said in a speech he gave in America some years ago was that science has supplanted religion as the source of knowledge about the cosmos and about life and everything, but it has failed utterly to give moral guidance, which of course is a thing that religion does. But he said, there are two exceptions in modern science. One is the anthropic principle which gives us some idea of why we're here, and the other is Gaia, which gives us something to be accountable to.

And this is the point about the Gaia notion, which I think could be important. It is based in science, so it can never be certain, we can never be absolutely sure about it, but it is something that we can put our trust in. We don't have to put our faith in it, because faith means belief in certainty, but we can put our trust in it. And there is a need for people to have something they can put their trust in. And if science succeeds in replacing religion altogether it would be most unfortunate because people do have that need and perhaps some concept like Gaia or some other which is science-based that people can put their trust in might be something that will be very helpful to civilisation in the future.

[Q] Great.

Okay.

[Q] I think we've…

I think we've covered a lot of ground, haven't we?

[Q] Yeah, covered a lot of ground.

I travel to a lot of labs, both now and in the past, government ones, big multinational companies, charities and so on. And one thing intrigues me very much, is the complaint by scientists that the bureaucrats and those responsible for the dispersal of public money expect them to put in outline management plans for their research, for sometimes as much as the next five years. This I find very amusing and quite absurd because how on Earth can science be predicted that far ahead? Imagine going to an artist anywhere and saying to him, 'Well if we're going to fund you for the next five years we want to know exactly what you'll be painting in five years' time'. He'll tell them to go away and so should the scientists. In real life, one never knows what one's going to do. You start out on a scientific course to find out something, but serendipitously, nearly always nature leads you off along another path, sometimes it's a good one and you find something far better than you'd ever imagined you would find on the first path. Sometimes of course it's a dead-end. But you can't predict it, the way it's going to go and one of my mentors early on said to me, and I can't remember which one it was, I think it was Sir Henry Dale, that it doesn't matter what you do in science as long as you keep your eyes open and I found there's a great deal of truth in that.

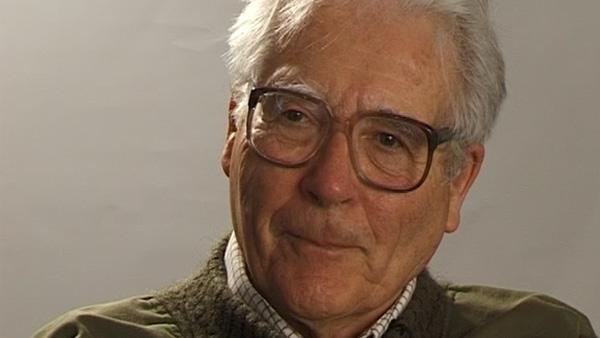

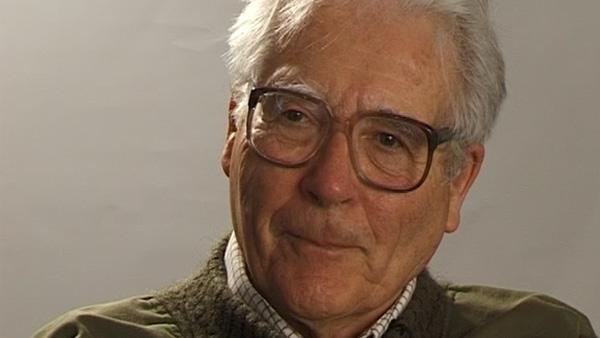

Born in Britain in 1919, independent scientist and environmentalist James Lovelock has worked for NASA and MI5. Before taking up a Medical Research Council post at the Institute for Medical Research in London, Lovelock studied chemistry at the University of Manchester. In 1948, he obtained a PhD in medicine at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, and also conducted research at Yale and Harvard University in the USA. Lovelock invented the electron capture detector, but is perhaps most widely known for proposing the Gaia hypothesis. This ecological theory postulates that the biosphere and the physical components of the Earth form a complex, self-regulating entity that maintains the climatic and biogeochemical conditions on Earth and keep it healthy.

Title: What I've learned from my life in science

Listeners: Christopher Sykes

Christopher Sykes is a London-based television producer and director who has made a number of documentary films for BBC TV, Channel 4 and PBS.

Tags: Star Trek, Vaclav Havel, Henry Dale

Duration: 4 minutes, 35 seconds

Date story recorded: 2001

Date story went live: 16 November 2010