NEXT STORY

Religion (Part 1)

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Religion (Part 1)

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. My home town and early life | 131 | 05:28 | |

| 2. School | 77 | 04:11 | |

| 3. Surendranagar town | 71 | 03:49 | |

| 4. My teacher and mentor Labshankar Raval | 73 | 04:46 | |

| 5. The Birdwood Library and Ravishankar Raval | 100 | 06:34 | |

| 6. More about my family | 78 | 06:36 | |

| 7. Religion (Part 1) | 83 | 03:58 | |

| 8. Religion (Part 2) | 65 | 03:30 | |

| 9. Reading, writing and painting | 69 | 03:47 | |

| 10. More about my childhood and my mother | 55 | 06:26 |

It was very difficult time. Economically we suffered a great deal, until my brothers got jobs. So, the early period was of, I would say, you know, living in difficult times and the family, as you know, because of the economic problems, you know, there would be all kinds of... and there are even quarrels. So, then we, you see, it’s a family, it’s in a way disassociated itself because of education, from the larger community of... you know, we were a community that dealt in oilseeds. So, we had the oilseed mill. That is a kind of a manual, you know... preparing oilseeds, and some were farmers and the rest of them had the community, had gone to Bombay and they were all dealing in what we call nut-bolts and things like that. Some of them had made money but most of them were either very low middle class and poor. So, in a way we were looked upon, yet perhaps slightly seen as outsiders, you know, even with, because also we had adopted a new surname. Sheikh is not our surname. I think it must have happened in my father’s time. My father must have adopted, many such communities in Gujarat and perhaps elsewhere have community names, but then, during the time of independence, I think, with some new opportunities coming their way, or idea of an identity emerging, which was a Muslim identity, and many communities adopted Muslim surnames. So, that is how this surname was... so, my father in a way was trying hard to make the community come out of, you know, it very, very, not only poor but also ignorance prevails and he wanted, you know, people to go send their children to school, you know, to come out, and I think he faced great resistance and even now, I would say, this community has remained almost at the same stage. After I came out of Surendranagar I have noticed that in the 50 years there have been less than 50 graduates. So, you can imagine, well, so we lived our life in a way. My father was very keen that children got jobs and government jobs which was secure jobs. My two brothers, when they got jobs, they both were married and that marriage took place, I think, together. And they lived in the same area, the same lane, and also in little hovels, you know, little... I think what we managed was in summer when we could sleep out. Again, that was a sort of outing. You know, it allowed you to dream because you slept in the street. But when people get married and they have children, how do you...? Well, it was a story of conflict also between brothers and father at time because economically we were not doing very well and my father had not managed his affairs. He was not a good either a, you know, businessman or, I don’t think he did ever any... he didn’t do any business but he didn’t make much money. So, I do carry some of the memories of the family conflict and, well, that is one. And I got my sort of support from external factors. So, I would spend time outside home. I’d go to either Shantibhai’s, I’d go to Labhshankar’s, you know, so, that were, these were kind of respite. These were kind of, in some ways they were sort of, what you call, proxy families. I became very close to Labhshankar and his wife. They literally sort of you know, I would go eat there and then became more and more involved in other activities. I think in a way my writing and painting, you know, became, you know, I could pay far more attention to that, you know, because I wanted to keep away from the problems at home. But my father was very sensitive to that. So, we had a little... we had three little, eventually had three little, what you call, house, homes, the rooms. They were our room. The one room was outside the, in the lane, and when I was very young, my grandfather lived there and he was there. When he died, I used that place for painting. I was able to sit there, you know, for hours to get the paint right etc. and I greatly enjoyed that and I liked people walking by, you know, on the street. And then I could go out and all that. So, I had my life. But my father was also a devout Muslim and he became more devout at the end of his life. So, he wanted all of us to pray. I, being the youngest, I was around, so I also prayed five times a day. I put on a cap. I hated that.

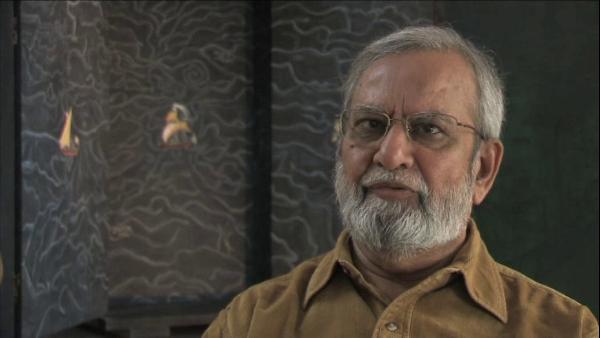

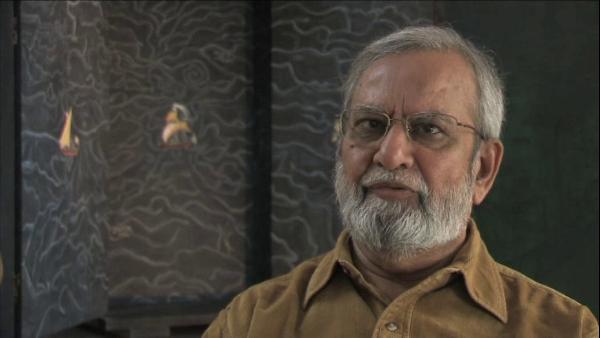

Gulammohammed Sheikh is an Indian painter, writer and art critic who has been a major figure in the Indian art world for half a century. His artistic career is closely associated with the renowned MS University of Baroda in Gujarat where after gaining his Master's degree, Sheikh went on to teach in the Faculty of Fine Arts, and where he was appointed Professor of Painting in 1982.

Title: More about my family

Listeners: Timothy Hyman

Timothy Hyman is a graduate of Slade School of Fine Art, London, in which he has also taught. In 1980 and 1982, he was Visiting Professor in Baroda, India. Timothy Hyman has curated many significant art exhibitions and has published articles and monographs on both European and Indian artists.

Duration: 6 minutes, 36 seconds

Date story recorded: December 2008

Date story went live: 17 November 2010