NEXT STORY

A golden opportunity for young scientists after World War II

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

A golden opportunity for young scientists after World War II

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11. An early understanding of basic physics | 1344 | 04:26 | |

| 12. Building an intercontinental missile in Buckminster Fuller's... | 1226 | 01:44 | |

| 13. Sidestepping the army draft by joining the Navy | 1104 | 01:11 | |

| 14. Meeting people in the Navy who couldn't swim | 1144 | 00:40 | |

| 15. Mathematical education in the US Navy | 1236 | 02:06 | |

| 16. Thinking the Hiroshima bomb was a hoax | 1765 | 01:43 | |

| 17. Inventing new mathematics | 1 | 1479 | 04:01 |

| 18. The careers I didn't choose | 1338 | 03:33 | |

| 19. My career was based on cowardice | 1534 | 02:19 | |

| 20. A golden opportunity for young scientists after World War II | 1073 | 03:30 |

And then when I got interested in making learning machines, I had great fortune to become friends with two young incredibly original professors, George Miller and Joe Licklider, and they were making up new kinds of theories about cognitive psychology. And at that time, in the late 1940s, they were way ahead of everyone else; it was sort of the time that Norbert Wiener’s Cybernetics was beginning to spread, and they understood those theories, and I understood them even better, and so that sort of made my decision for me. That is, here was this new field called cognitive psychology, and I was really good at it, getting new ideas, and except for a few other people like Sigmund Freud and William James, who maybe had better ideas than I did, there wasn’t much competition. Licklider and Miller were… accepted me as an equal, and so you could say that my career was based on cowardice, or… or something. If there was a field where there were five or 10 people who were better at it, why bother? Because in these fields, you know, if you were a very good physicist and you ran across a Richard Feynman, what’s the use?

And I was a… quite a good physicist, actually, but I had the fortune to run across Richard Feynman, again we became friends, and I wrote a… in fact I wrote a nice paper that he liked enough to publish, but… but I couldn’t see being serious about it, because with people like Murray Gell-Mann and Alex Rich, and people like that.

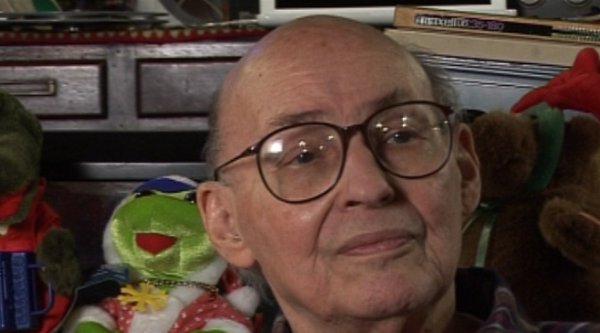

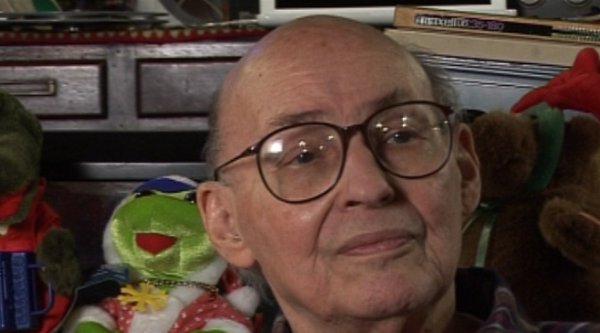

Marvin Minsky (1927-2016) was one of the pioneers of the field of Artificial Intelligence, founding the MIT AI lab in 1970. He also made many contributions to the fields of mathematics, cognitive psychology, robotics, optics and computational linguistics. Since the 1950s, he had been attempting to define and explain human cognition, the ideas of which can be found in his two books, The Emotion Machine and The Society of Mind. His many inventions include the first confocal scanning microscope, the first neural network simulator (SNARC) and the first LOGO 'turtle'.

Title: My career was based on cowardice

Listeners: Christopher Sykes

Christopher Sykes is a London-based television producer and director who has made a number of documentary films for BBC TV, Channel 4 and PBS.

Tags: 1940s, Cybernetics, Cybernetics: Or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine, Joseph Licklider, George Miller, Norbert Wiener, Sigmund Freud, William James, Richard Feynman, Murray Gell-Mann, Alexander Rich

Duration: 2 minutes, 20 seconds

Date story recorded: 29-31 Jan 2011

Date story went live: 09 May 2011