NEXT STORY

Losing fellow pilots on take off

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Losing fellow pilots on take off

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11. 'Little did we know how dangerous these bloody rockets were!' | 269 | 01:55 | |

| 12. Trying to avoid being hit by our own explosions | 227 | 02:00 | |

| 13. Finally getting commissioned | 193 | 01:33 | |

| 14. Defence mechanism against getting too emotional | 206 | 02:40 | |

| 15. 'I knew everybody was shooting at me' | 214 | 02:12 | |

| 16. Friendly fire | 192 | 04:43 | |

| 17. Losing fellow pilots on take off | 215 | 02:09 | |

| 18. The 'cab rank' | 184 | 03:10 | |

| 19. 'Order me a late tea' | 1 | 214 | 02:54 |

| 20. Norman Merrett | 1 | 175 | 03:44 |

It was a very sad experience. We were still straight fighters stationed at Manston, and I was very keen to get on what we called a show, which in this case was to escort some American B-52s, I think, were about to bomb Abbeville aerodrome, and... I was the last one to run out to my plane – I was the oldest plane in the action. But I was the new one, remember, and the plane didn't have long-range tanks, but I was very keen, and I took off with the rest of the squadron, and we kept circling above Beachy Head where we were supposed to meet the Americans. And we lost, I think, 12 minutes or 13 minutes before they turned up. And then we went straight across the Channel, and as we were crossing into France my engine cut on main tanks and I had to switch over to reserve tanks. But now the reserve tanks are smaller than the main tanks, and so I rang up my squadron commander, who was a brilliant man called Thornton-Brown, and I said, 'You know, I have a bit of a problem. I'm flying... I have no long-range tanks... I'm flying on reserve tank'. And he said, 'You bloody fool', because we were flying at, what, 20,000 ft or pretty high up. He said, 'Reduce your revs, get a homing from Manston, and without... try to go straight back to Manston', and so on, which I did.

And on my way back to Manston I heard all sorts of chatter on the radio, and what had happened, that we had a high level cover of American Mustangs or Thunderbolts, and they had never seen a Typhoon before, and they went down to attack. There were, I think, five men left. They shot down Thornton-Brown, they shot an American pilot who was a famous ice hockey player – he was shot down, but thank God, managed to get a forced-landing, and another one was shot down. So we lost three pilots because of bad recognition – well, friendly fire, as you would call it today. And from that time on, incidentally, the black and white stripes were… and when Artie Ross was well again, we sent him to every American fighter station to show off the Typhoon.

And it was very, very sad, and years, years later in films, about six years ago, maybe seven years ago – don't want to bore you with the length of the story, because this is quite a long story – when we were night-shooting in New York with an English cameraman who was living in Brighton and he was telling me, you know, I'm very friendly with a woman who writes very nice poetry, but she had a terrible time because her husband was shot down by friendly fire. And that's how I found out that she was the wife of Thornton-Brown, and the moment I came back here we got together. She married again and had children, but she's never forgotten Thornton-Brown. And the sad part was that it took a long time before she was informed really what had happened to him, you know, so you've got those things too…

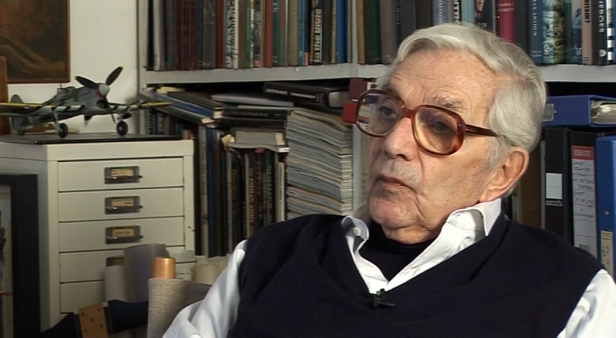

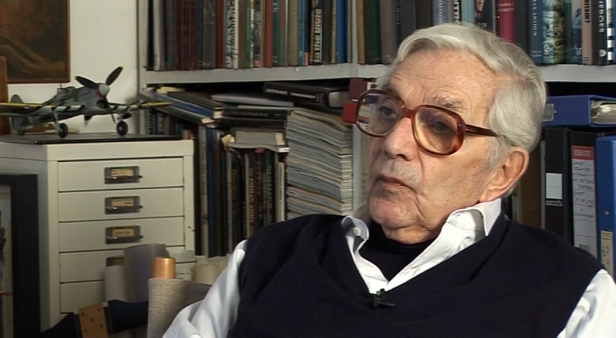

Sir Kenneth Adam (1921-2016), OBE, born Klaus Hugo Adam, was a production designer famous for his set designs for the James Bond films of the 1960s and 1970s. Initially, he trained as an architect in London, but in October 1943, he became one of only two German-born fighter pilots to fly with the RAF in wartime. He joined 609 Squadron where he flew the Hawker Typhoon fighter bomber. After the war, he entered the film industry, initially as a draughtsman on This Was a Woman. His portfolio of work includes Barry Lyndon and The Madness of King George; he won an Oscar for both films. Having a close relationship with Stanley Kubrick, he also designed the set for the iconic war room in Dr Strangelove. Sir Ken Adam was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II in 2003.

Title: Friendly fire

Listeners: Christopher Sykes

Christopher Sykes is an independent documentary producer who has made a number of films about science and scientists for BBC TV, Channel Four, and PBS.

Tags: Manston, Abbeville Aerodrome, Beachy Head, English Channel, France, USA, New York, Brighton, World War II, Art Ross

Duration: 4 minutes, 43 seconds

Date story recorded: December 2010 and January 2011

Date story went live: 15 August 2011