NEXT STORY

What I want to be remembered for

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

What I want to be remembered for

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 61. The Uncertain Art | 184 | 03:02 | |

| 62. The review of The Art of Ageing | 213 | 04:36 | |

| 63. Depression returns | 503 | 03:28 | |

| 64. Appreciation of family and friends | 270 | 02:27 | |

| 65. A wonderful life | 1 | 274 | 02:58 |

| 66. Coming to terms with my father | 348 | 04:39 | |

| 67. What I want to be remembered for | 351 | 02:15 |

[Q] Well, there's something, you know, that you haven't probably talked about that much.

What's that?

[Q] The power of your father over you and your life.

You know, after I wrote Lost in America, and I wrote it for myself. I wrote that book because I felt there were things I would never understand unless I wrote about them. I've talked about the fact that when I write, I find out what I'm really thinking, as so many people, so many writers will tell you. When I finished that book, and it was not a huge bestseller. Even to this day, it's sold, I think, 29,000 copies, which is pretty good, but, you know, it's not a huge, big deal. But when I was on the book tour, and even now, when I go to give a talk, there's always going to be someone who wants to talk about that book. And I've gotten, of course, many letters about it. But the most common question I was asked at the beginning, and I'm still asked from time to time, is, 'Do you forgive your father?' And the first time someone asked that question, I said, 'Forgiveness has nothing to do with this'. It's not as if my father deliberately did anything to me. This is the way he was, he had no control. He had no control over his syphilis, he had no control over how he must have felt, ridiculed, debased by all of this, how it must have had some influence on his never assimilating. It's not a question of forgiving him. Now I understand him. And I never had understood him before. When I began to write that book, bit by bit by bit, I understood him more, and I understand him, I think, very well, to this day. To people… who hear about him without reading that book, but have just heard… he seems like an ogre. And maybe he was an ogre, but I never hated my father. I loved my father. He did me an awful lot of damage. And when I crashed, then I began to recognize just how bad that damage was, including the fact that when I was recovering, this wonderful psychiatrist, this young man who would later finish training and became the person I was seeing, said to me at one point, you know, you're never really going to get completely better until you come to terms with your father.

And that's really why I wrote the book, so I could come to terms with what he was, how he became that way and why he treated me the way he did, and his wife, my mother, the way he did, some other people that way. And it was clear that this was not a bad person. This was not an unloving person. This was a man who didn't know how to express love. This was a man who felt so debased by life. Imagine going to a public clinic for his various syphilitic problems and being treated like dirt, as the way the clerks and some of the nurses and some of the doctors treated people in those days. I think one of the major reasons that I feel so strongly about the need for humanism, humanitarianism, for the milk of human kindness among physicians, is because of my experiences watching the way my father was treated, in this really inhuman way. And, you know, ever since I became a doctor, it's always been my feeling that the greatest thing I can give to my patients is myself. And that's what I've tried to do. Who knows how successful I've been, but that's what I've tried to do.

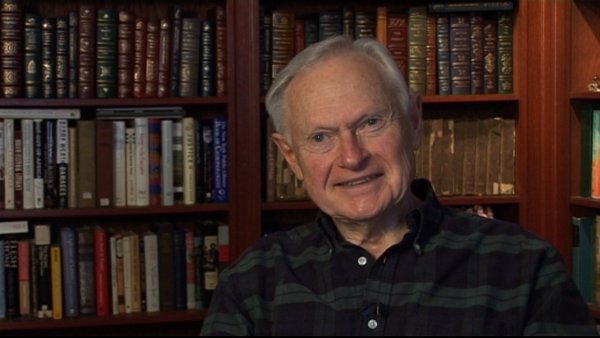

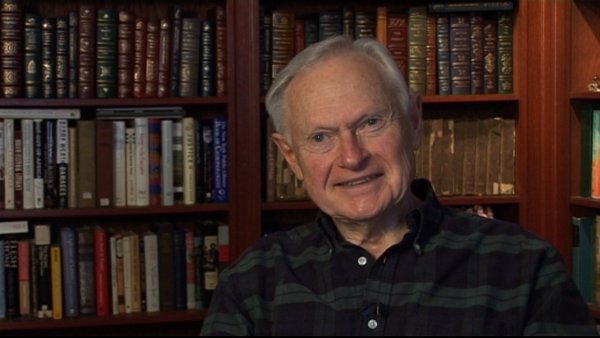

Sherwin Nuland (1930-2014) was an American surgeon and author who taught bioethics, the history of medicine, and medicine at the Yale University School of Medicine. He wrote the book How We Die which made The New York Times bestseller list and won the National Book Award. He also wrote about his own painful coming of age as a son of immigrants in Lost in America: A Journey with My Father. He used to write for The New Yorker, The New York Times, Time, and the New York Review of Books.

Title: Coming to terms with my father

Listeners: Christopher Sykes

Christopher Sykes is a London-based television producer and director who has made a number of documentary films for BBC TV, Channel 4 and PBS.

Tags: Lost in America

Duration: 4 minutes, 39 seconds

Date story recorded: January 2011

Date story went live: 04 November 2011