NEXT STORY

Dialogue

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Dialogue

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 151. John Updike: 'He rarely made a vulgar error' | 793 | 01:39 | |

| 152. The Updike Beck books | 1 | 662 | 00:28 |

| 153. What tells you a book's not right for you? | 743 | 00:41 | |

| 154. 'I catch them where they're weak' | 422 | 03:39 | |

| 155. Everyman | 302 | 00:51 | |

| 156. Indignation | 221 | 00:41 | |

| 157. The Humbling | 196 | 01:03 | |

| 158. Nemesis and the destruction of the strong man | 270 | 02:36 | |

| 159. The inner ear | 442 | 03:21 | |

| 160. Dialogue | 471 | 01:09 |

How do you get the sentences to have some power at the same time that you're being accurate in your description or presentation of whatever is on your mind? I suppose you have an interior metronome which is clicking out the rhythms for you. And you have your kind of sentence, now every sentence is different... and every sentence has a different... falls a different way. But altogether you have kinds of sentences you make. It's in your own inner... inner ear. Do I read aloud to test the sentences out? Very rarely. Very rarely. Sometimes if a paragraph is... is difficult and no good, then I'll stop and sit in a chair and read it and try to see what's wrong with it. But I... rather than hearing it, I'm helped by seeing it. So I have to just keep seeing it on the screen.

Now years ago when I wrote The Counterlife, which I think is 1985, I had an editor at Farrar Straus, who were then my publishers, named David Rieff. And David is a... was a genius editor. And... I was in England and I came to New York to give him the manuscript of the book and he read it and I read it and I thought there's something... there's wrong with it. And so one day and evening, we sat in my room in the hotel and I read this book aloud to him. And whenever the sentence was weak, one or the other... other of us rang the gong, you know. And it's... it's wrong, and where... where is it wrong? Where is it wrong? So I did it with the help of somebody else. You hope you have an editor who can help you out when you're in trouble like that. Those are the best editors... are the ones who can... who can help you out with the sentence, you know. But by and large you rely on yourself and by and large, as I said, there's this inner ear, inner metronome that ticks out the rhythm and that gives you the sentences, the cadences.

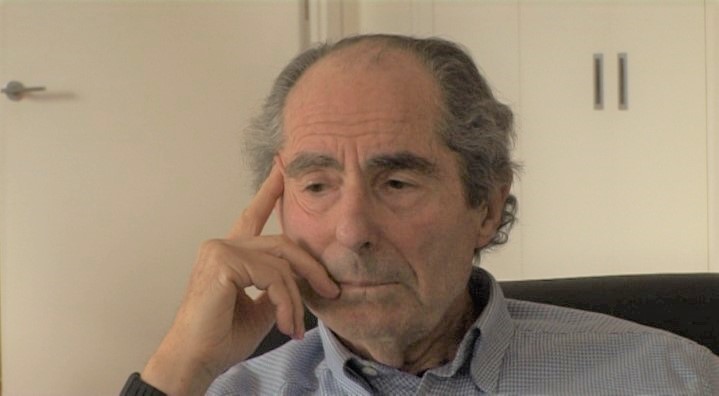

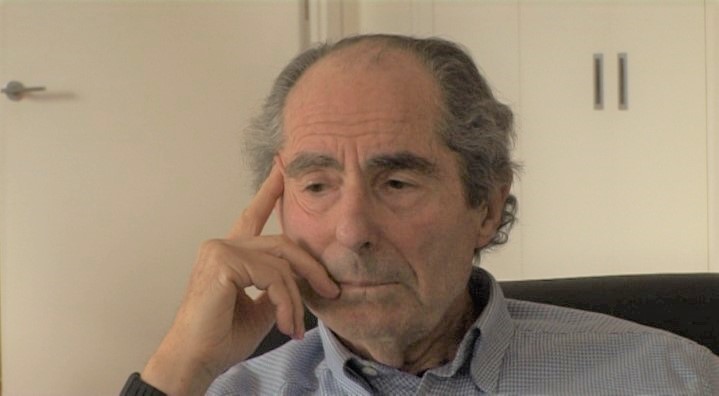

The fame of the American writer Philip Roth (1933-2018) rested on the frank explorations of Jewish-American life he portrayed in his novels. There is a strong autobiographical element in much of what he wrote, alongside social commentary and political satire. Despite often polarising critics with his frequently explicit accounts of his male protagonists' sexual doings, Roth received a great many prestigious literary awards which include a Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 1997, and the 4th Man Booker International Prize in 2011.

Title: The inner ear

Listeners: Christopher Sykes

Christopher Sykes is an independent documentary producer who has made a number of films about science and scientists for BBC TV, Channel Four, and PBS.

Tags: The Country Life

Duration: 3 minutes, 21 seconds

Date story recorded: March 2011

Date story went live: 18 March 2013