NEXT STORY

Travelling after the war was a huge adventure

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Travelling after the war was a huge adventure

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 31. Art is my addiction | 450 | 02:00 | |

| 32. Why Oxford was not for me | 353 | 03:51 | |

| 33. Too young for The Courtauld | 238 | 03:48 | |

| 34. Intellectual stimulation during my student days | 251 | 03:50 | |

| 35. The best way to view works of art | 294 | 04:34 | |

| 36. Travelling after the war was a huge adventure | 246 | 02:19 | |

| 37. Humiliation during National Service | 300 | 03:45 | |

| 38. Dealing with life in the army | 254 | 04:01 | |

| 39. Valuable lessons learned in the army | 241 | 03:12 | |

| 40. 'Any fool can be uncomfortable' | 312 | 02:37 |

[Q] In art history, why is it so important to actually look at the actual paintings, and why can’t you learn all about it from books?

I think that’s the silliest question I’ve ever been asked, but on your side, you have art historians like Gombrich, for example. I’m absolutely convinced that Gombrich is an art historian who is much more interested in ideas than in art, and as long as he had an image of some kind, he could work with it. It might be an outline image of some classical sculpture, you know, and that’s enough for him. He didn’t need to have the classical sculpture. He could… all he needed from the Apollo Belvedere was the image. He didn’t need the experience. I’m sure he had the experience, but I’m not sure that it enriched his ideas about such things. Whereas my response, and I think the response of anybody who is a really… is interested in the art more perhaps than the idea, you need the paint on canvas. You need to see it. You need to be able to walk around a sculpture. If you are looking at Michelangelo’s David… I remember that Johannes Wilde, who was the greatest, the most marvellous of teachers at the Institute, always said, in his lectures, that it was like a high relief. And of course, as you walk into the Accademia in Florence, there it is at the far end, in the niche, and it does look like a high relief, because you only see its front. But when you get to it, there is something very subtle about the movement, the way the arm falls and the other one rises, and the tilt of the buttocks and the bending of the spine, that actually draws you round, and as you move round, you are drawn still further round, so you are walking around the back of the thing, you’re in the depth of the arch. And it is still exciting. You’re too close to it, but you are still aware of the movement that is inherent in this great chunk of marble. And so Michelangelo quite clearly meant it to be free-standing. He meant you to walk around it. It was never meant to stand in a niche, it was never meant to be up against a wall. And to me, it’s an example of where you have a really great teacher who is wrong.

But Gombrich would have been quite content with a head-on photograph, because that is the most influential view of the sculpture, and anyone who has translated that sculpture into an element in a painting, for example, has always taken that view. So in terms of the transmission of ideas, that view is all he needs. The actual experience of looking at it, doing what it’s instructing you to do… my belief is that every single work of art you look at has a viewpoint which is determined by the sculptor or the painter. If it’s a painting, the painting will tell you: stand here. The picture may be like that, but the painter… the spectator is meant to stand here, because the whole structure of the composition directs him to do so.

You have a piece of sculpture which doesn’t instruct you to move, so you will find that there is an ideal point from which it should be viewed. And then you will find many sculptures which actually compel you to circulate.

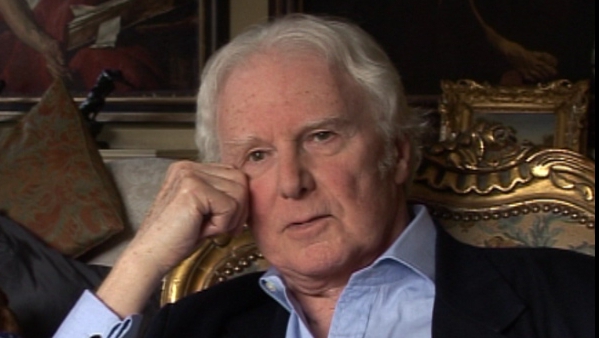

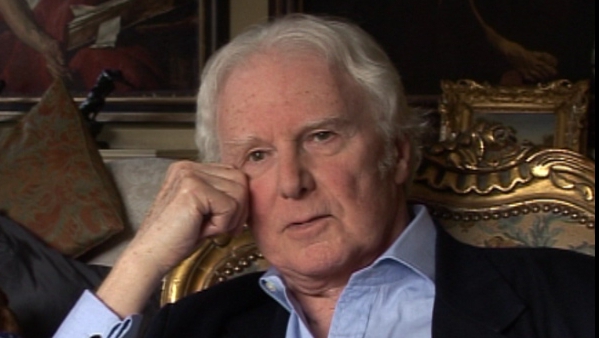

Born in England, Brian Sewell (1931-2015) was considered to be one of Britain’s most prominent and outspoken art critics. He was educated at the Courtauld Institute of Art and subsequently became an art critic for the London Evening Standard; he received numerous awards for his work in journalism. Sewell also presented several television documentaries, including an arts travelogue called The Naked Pilgrim in 2003. He talked candidly about the prejudice he endured because of his sexuality.

Title: The best way to view works of art

Listeners: Christopher Sykes

Christopher Sykes is an independent documentary producer who has made a number of films about science and scientists for BBC TV, Channel Four, and PBS.

Tags: Michaelangelo's David, Apollo Belvedere, Galleria dell'Accademia di Firenze, Gallery of the Academy of Florence, Ernst Hans Josef Gombrich, Michaelangelo, Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni, Johannes Wilde

Duration: 4 minutes, 34 seconds

Date story recorded: April 2013

Date story went live: 04 July 2013