NEXT STORY

Lost in translation: how not to compile a catalogue

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Lost in translation: how not to compile a catalogue

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 51. Titian's Assumption of the Virgin | 286 | 02:22 | |

| 52. Modern transport robs the traveller of the joy of discovery | 204 | 04:14 | |

| 53. Anthony Blunt and Johannes Wilde | 274 | 06:00 | |

| 54. How The Courtauld grew in prestige under Anthony Blunt | 251 | 04:58 | |

| 55. Notable alumni of The Courtauld | 225 | 01:13 | |

| 56. Working to fund my PhD | 202 | 04:42 | |

| 57. Too late to return to academia | 198 | 04:42 | |

| 58. Potential pitfalls in preparing an exhibition | 176 | 02:37 | |

| 59. Lost in translation: how not to compile a catalogue | 188 | 01:50 | |

| 60. Temperamental differences and a damaged Delacroix | 188 | 05:55 |

In putting an exhibition together, your very first thing is your list of desirable loans. So you have that list. This is perfection. And then you find that something which is really rather crucial to perhaps the internal argument of the exhibition, can’t be borrowed. It may be promised to some other exhibition, it may be in too fragile a condition to travel. And so you can’t have it, so you have to find something else. And that means you’re really back... sort of, going through all the possibilities of… we want a picture which demonstrates precisely the same thing. Where are we going to find it? This museum, that museum? You have to know something about the alternatives. You then have to find out whether the alternatives themselves are going to be possible. And you might… and it does happen. You might get not only the first refusal, but a second and a third and a fourth refusal. So you end up with a picture, if you’re determined to follow this argument through, you may end up with a picture that you’ve never seen.

And I will give you an example, not one in which I was involved, but there was an exhibition at the Royal Academy some donkey’s years ago, to which a picture from São Paulo in Brazil was sent. And I said, for God’s sake, why did you ask for that heap of rubbish? It must have cost a fortune to get it here, and it’s in appalling condition. And of course it transpired that precisely the process I’ve just described had been gone through and the last thing that they thought would demonstrate the point was the picture that they knew only from reproductions or photographs. And, of course, it was a disaster when it arrived. But they had to put it in, because it was the logical sort of chink in the argument, that this picture could fill.

So that’s one thing. Another… you learn from working on an international exhibition that there are problems in translation.

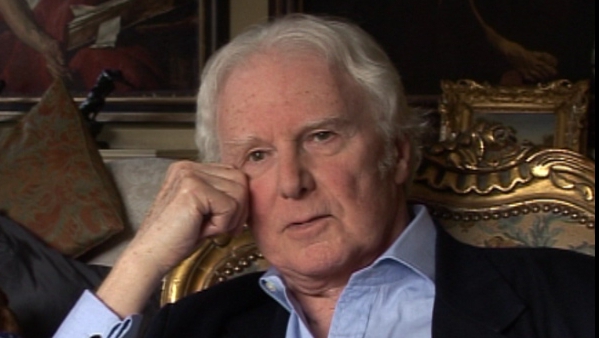

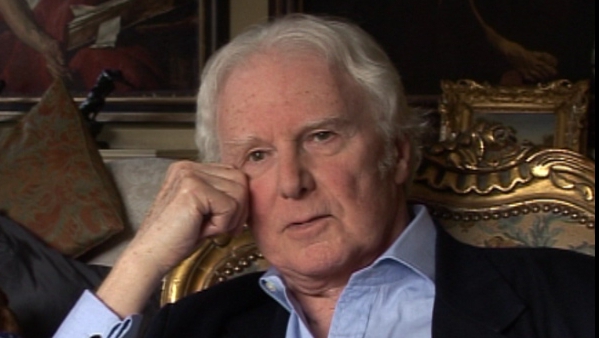

Born in England, Brian Sewell (1931-2015) was considered to be one of Britain’s most prominent and outspoken art critics. He was educated at the Courtauld Institute of Art and subsequently became an art critic for the London Evening Standard; he received numerous awards for his work in journalism. Sewell also presented several television documentaries, including an arts travelogue called The Naked Pilgrim in 2003. He talked candidly about the prejudice he endured because of his sexuality.

Title: Potential pitfalls in preparing an exhibition

Listeners: Christopher Sykes

Christopher Sykes is an independent documentary producer who has made a number of films about science and scientists for BBC TV, Channel Four, and PBS.

Tags: Royal Academy of Arts

Duration: 2 minutes, 37 seconds

Date story recorded: April 2013

Date story went live: 04 July 2013