NEXT STORY

Joining the Merchant Marine

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Joining the Merchant Marine

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11. Why we published The Satanic Verses | 39 | 06:06 | |

| 12. Joining the Merchant Marine | 28 | 02:49 | |

| 13. Following in the footsteps of Joseph Conrad | 31 | 01:31 | |

| 14. Having a principled background | 43 | 02:48 | |

| 15. Being creative in Spain | 1 | 32 | 03:27 |

| 16. My career in publishing begins | 30 | 04:22 | |

| 17. Catching the publishing 'bug' | 29 | 02:18 | |

| 18. Paying my way in life | 44 | 03:08 | |

| 19. Losing my fears in the laundromat | 33 | 03:14 | |

| 20. In search of solitude | 34 | 03:07 |

In the case of the famous book that I had some significant involvement in, Salman Rushdie's The Satanic Verses, there were many people who told me that I should stop publishing the book, and as there was loss of life connected with its publication, and might have been more, including our own staff at Penguin, you had to balance that, or try to. The kinetic possibility that people would lose their life in defending a principle that was honoured until it was not in the interest of a very vocal minority, minority certainly in Western countries.

I took the view that we live in the West, and the principles, not only of the French Revolution, but all those principles that emerged from the freedoms that were won then, that are part of our patrimony, they all had to be preserved, that our liberties would be curtailed. If any particular minority could forbid any book, then some Catholic book would offend the Church, and Catholics might say, if you continue to publish this book, we will kill you, it should be banned, or some Jewish group would be offended by something, and some Jewish book was not published or some book about Judaism were not published. I think it's easier to publish everything, and to have a debate.

But at least 70 people died, as a result of The Satanic Verses, some in India. I think there were attacks in Japan and Italy and Norway and Belgium and I don't know where else. So these are terrible decisions that I never thought I would ever have to make. But I wasn't personally involved in the question of Salman Rushdie's life, I of course didn't want him to lose his life, and when we published it, published the book, did I ever imagine what would ensue after we published the book. Nor did I entirely understand how upset Muslims would be by the publication of the book; I didn't have a background in Islam. In fact, when the Ayatollah issued his fatwa, I knew he hadn't read the book himself, he didn't read English and the book hadn't been translated. So there was a fraudulent aspect to the attack on the book.

But it was the book and the concept that I believed one had to defend, because once you give in to terrorists you are finished. They will do more, that's the argument behind the non-ransoming of hostages when they are kidnapped. Everybody would want to have these hostages freed, but if we pay for this, there will be more kidnappings and more hostages. Well, once you say, I won't publish a book, because someone doesn't like it or someone threatens you, you're finished. Some other group will do the same thing, or the same group will do it more.

So I took the view that I did, and Penguin followed that lead or was with me, however you want to put it, for a basic social civic, political intellectual reason. It was the freedom of ideas. Obviously, since I knew Salman, I had all sorts of positive feelings for Salman and his plight, but the issue was even bigger than he was, and he is a very good writer.

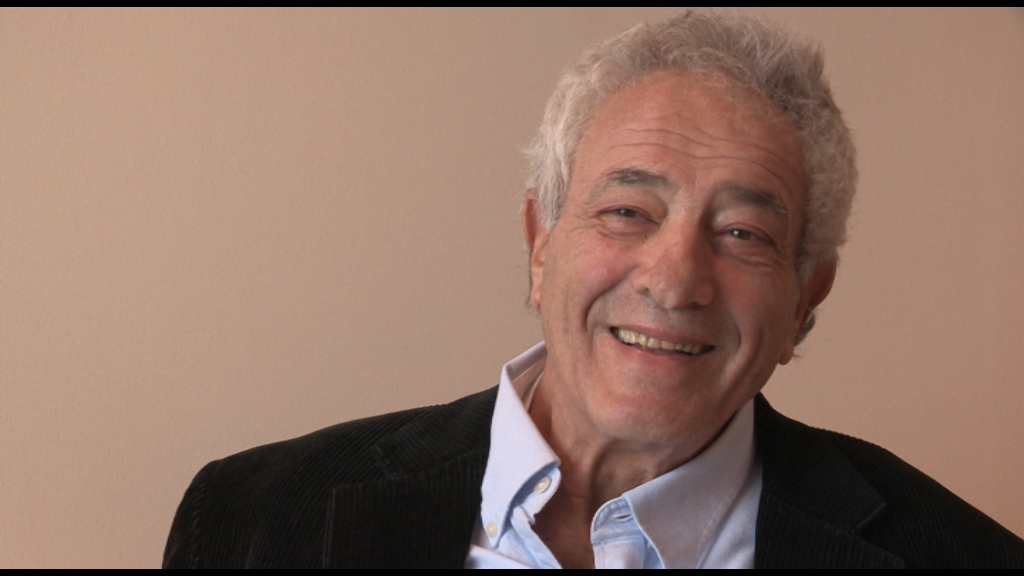

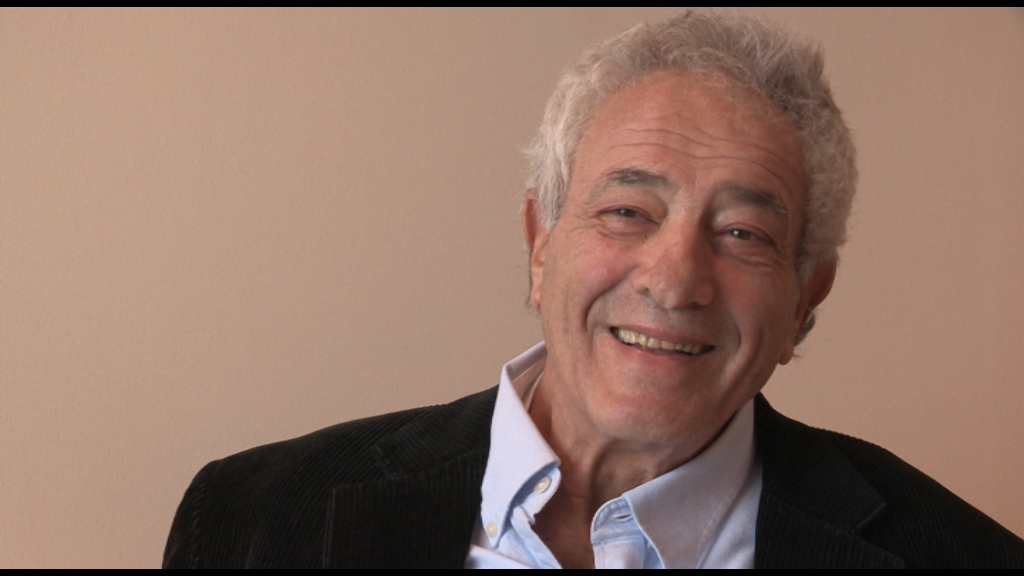

Peter Mayer (1936-2018) was an American independent publisher who was president of The Overlook Press/Peter Mayer Publishers, Inc, a New York-based publishing company he founded with his father in 1971. At the time of Overlook's founding, Mayer was head of Avon Books, a large New York-based paperback publisher. There, he successfully launched the trade paperback as a viable alternative to mass market and hardcover formats. From 1978 to 1996 he was CEO of Penguin Books, where he introduced a flexible style in editorial, marketing, and production. More recently, Mayer had financially revived both Ardis, a publisher of Russian literature in English, and Duckworth, an independent publishing house in the UK.

Title: Why we published "The Satanic Verses"

Listeners: Christopher Sykes

Christopher Sykes is an independent documentary producer who has made a number of films about science and scientists for BBC TV, Channel Four, and PBS.

Tags: The Satanic Verses, Penguin Books, Salman Rushdie

Duration: 6 minutes, 6 seconds

Date story recorded: September 2014-January 2015

Date story went live: 12 November 2015