NEXT STORY

Science fiction writers can be perceptive

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Science fiction writers can be perceptive

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 71. My wife Margaret | 70 | 05:04 | |

| 72. I have always continued to write | 46 | 02:30 | |

| 73. Contemplating the end of life | 106 | 03:32 | |

| 74. The durability of love | 63 | 04:23 | |

| 75. Love is not a straightforward business | 47 | 05:52 | |

| 76. Mad with love | 106 | 01:48 | |

| 77. Research – the key to making my stories credible | 43 | 06:26 | |

| 78. Science fiction writers can be perceptive | 52 | 01:32 | |

| 79. I’m a sort of artist | 38 | 02:14 |

Quite frequently, one has to research something, to make it sensible. And, for instance... what was the title of my book? The Finches of Mars, all right? The Finches of Mars. There, I thought, that if women went to Mars, and that itself was slightly a contradiction to all the American stories I'd written... I'd read stories set on Mars, where chaps go tramping over it, etc., never a woman, never a woman! And so, Finches of Mars, was going to be about the colonisation of Mars and mainly featuring women. But then the thought occurred to me that if women were on a lighter planet, they might have difficulty generating children when they were pregnant.

And so I found the address of a man – his name is in the book – who was in charge of… perhaps it was called Women's Problems. No, it wasn't. Anyhow, it was in a hospital in New York, and he did specialise in women's problems. So I wrote to him and asked him if he didn't think that if women went to Mars and were pregnant, if they mightn't have stillborn children. And he wrote back quite fully, saying he thought that would be the case. Do you see where that idea came from? From my mother, who had, first of all, given birth to a stillborn baby.

So, with that information, I was able to start and write the novel, and with other bits of stuff that one throws in, or indeed, throws out.

But, when I came to write the Helliconia Trilogy, for two years I did research on that and this is one of the advantages of living in Oxford: if you want to know anything, you only have to go to an aging professor and knock on his door, and he comes out and he will tell you all that you want to know, and more. Certainly, and more. But there were some who were vastly helpful. For instance... oh, he's retired now... he used to live quite near here... and what was his name? Oh, it's so infuriating that I don't remember names. He told me about breathable air and certain qualities that were needed that were not often referred to. And that was very useful, too.

And I went on gathering these facts so that Margaret, my wife, said to me, 'Are you ever going to write this book?' So I said, 'Well, I hope to, but I just need… I just need a few more facts'. And I did need a few more facts. One of the things... I'd got the whole geography of the place, and also its role in the cosmos and where it was and the cosmic accident that made it the kind of planet that it was.

And… but I couldn't… couldn't see how the vegetation was going to be. And then one evening, I was going by train from Oxford up to London, passing through Didcot and as it happened, Didcot Power Station was letting off steam. The six chimneys were letting off steam and the sun was behind them so that the steam was black; it was quite unmistakably black. And, looking at it, I could say to myself, my God – it's a Helliconian tree! And that was the key that enabled me to start because the trees did look like that, but, when winter came, instead of shedding leaves, everything was withdrawn into this vast trunk and sealed over with a kind of exudation of wax. That's the way it could all work.

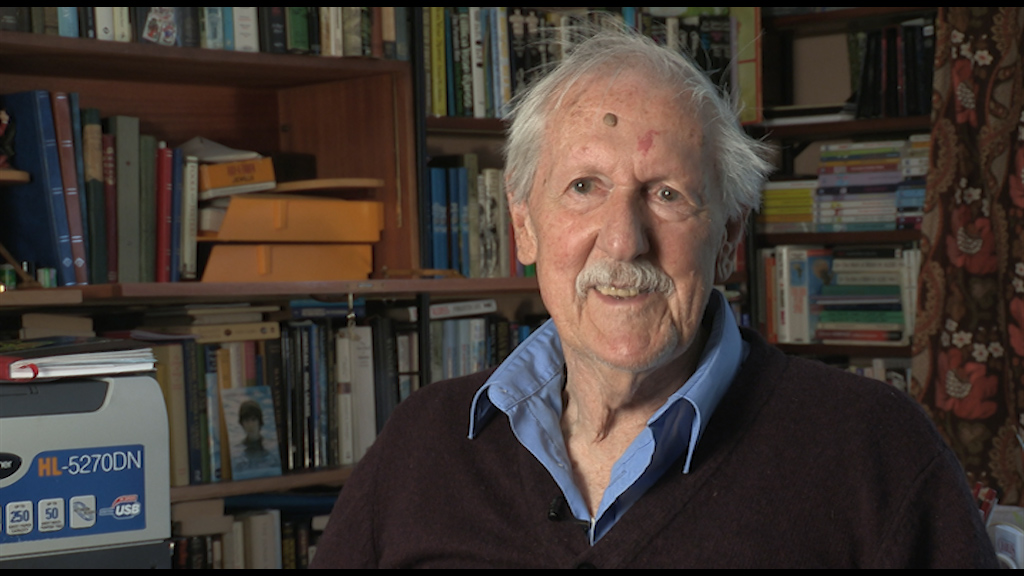

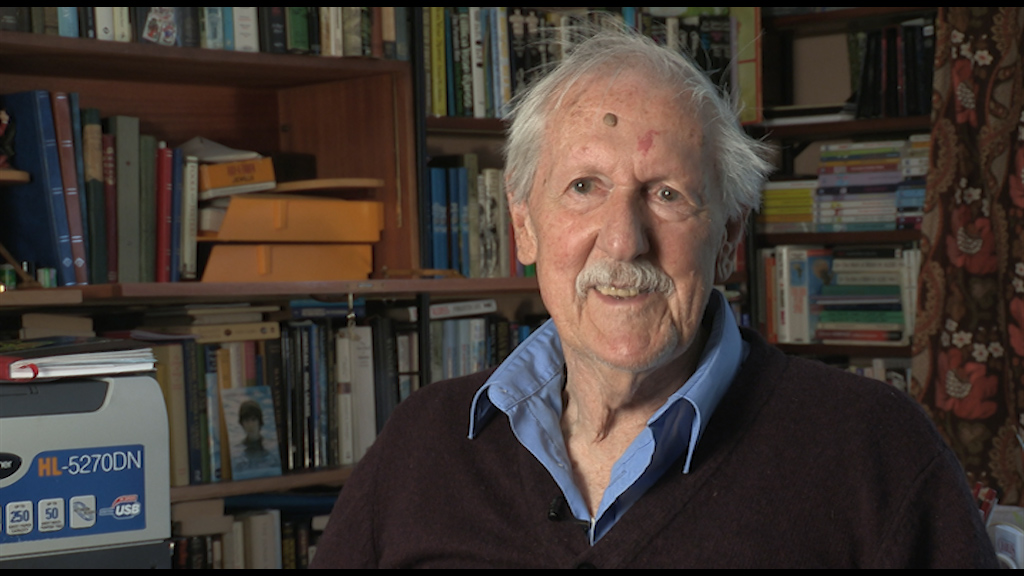

Brian Aldiss (1925-2017) was an English writer and anthologies editor, best known for his science fiction novels and short stories. He was educated at Framlingham College, Suffolk, and West Buckland School, Devon, and served in the Royal Signals between 1943-1947. After leaving the army, Aldiss worked as a bookseller in Oxford, an experience which provided the setting for his first book, 'The Brightfount Diaries' (1955). His first science fiction novel, 'Non-Stop', was published in 1958 while he was working as literary editor of the 'Oxford Mail'. His many prize-winning science fiction titles include 'Hothouse' (1962), which won the Hugo Award, 'The Saliva Tree' (1966), which was awarded the Nebula, and 'Helliconia Spring' (1982), which won both the British Science Fiction Association Award and the John W Campbell Memorial Award. Several of his books have been adapted for the cinema. His story, 'Supertoys Last All Summer Long', was adapted and released as the film 'AI' in 2001. His book 'Jocasta' (2005), is a reworking of Sophocles' classic Theban plays, 'Oedipus Rex' and 'Antigone'.

Title: Research – the key to making my stories credible

Listeners: Christopher Sykes

Christopher Sykes is an independent documentary producer who has made a number of films about science and scientists for BBC TV, Channel Four, and PBS.

Tags: Finches of Mars, Mars, Helliconia Trilogy, Didcot Power Station

Duration: 6 minutes, 26 seconds

Date story recorded: September 2014

Date story went live: 17 August 2015