NEXT STORY

Coincidences that influenced my work

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Coincidences that influenced my work

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 41. Cell accepts my article for publication | 108 | 03:09 | |

| 42. Discovering the machinery for turning on long-term memory | 82 | 03:08 | |

| 43. Investigating the initiation and maintenance of long-term memory | 52 | 05:28 | |

| 44. What is so special about prions? | 77 | 04:42 | |

| 45. The characteristic features of prions | 53 | 01:34 | |

| 46. Alden Spencer | 53 | 05:12 | |

| 47. S Channel | 34 | 01:50 | |

| 48. How a review inspired a textbook | 48 | 02:19 | |

| 49. Coincidences that influenced my work | 70 | 04:39 | |

| 50. Nurturing the ideas of post-doc students | 56 | 00:54 |

When I was still at Harvard, I was in constant contact with Alden Spencer, in part because I was eager for him to come to Harvard – he wanted to leave Oregon – and also because we had formulated a parallel strategy. He had carried out in the spinal cord experiments dealing with habituation, actual behavior habituation. And he wasn't able to reduce it to monosynaptic level, but nonetheless was able to see changes in synaptic strength, and we realized that a cellular approach was going to be extremely productive to studying learning and memory. So we wrote a review together for Physiological Reviews that came out in the early 1960s called “Cellular Neurophysiological Approaches in the Study of Learning” which really encouraged people who were cellular physiologists to get interested in behavior and learning. And we spelled out a number of strategies, including analogues of learning, but pointed out that the real challenge was to explore real instances of learning, and indicated how this might be done.

So we got a great deal of pleasure doing this. We learned a great deal from doing it, and I think the review was quite influential. And it started a trend in my own thinking of periodically writing reviews, which led to my later writing, the Cellular Basis of Behavior, and then getting inspired to do a textbook of neural science. And one of the things that we did at Columbia, once we got there, was to take the syllabus that we had at NYU, expand it, make it even better, include illustrations, and after a while we said, this is too good for just Columbia students. We should make a book out of it. We called it modestly Principles of Neural Science. And did extremely well. It's now in its fifth edition, and it's often considered the standard textbook in the field. It's gotten two awards, and we're looking forward to doing the sixth edition.

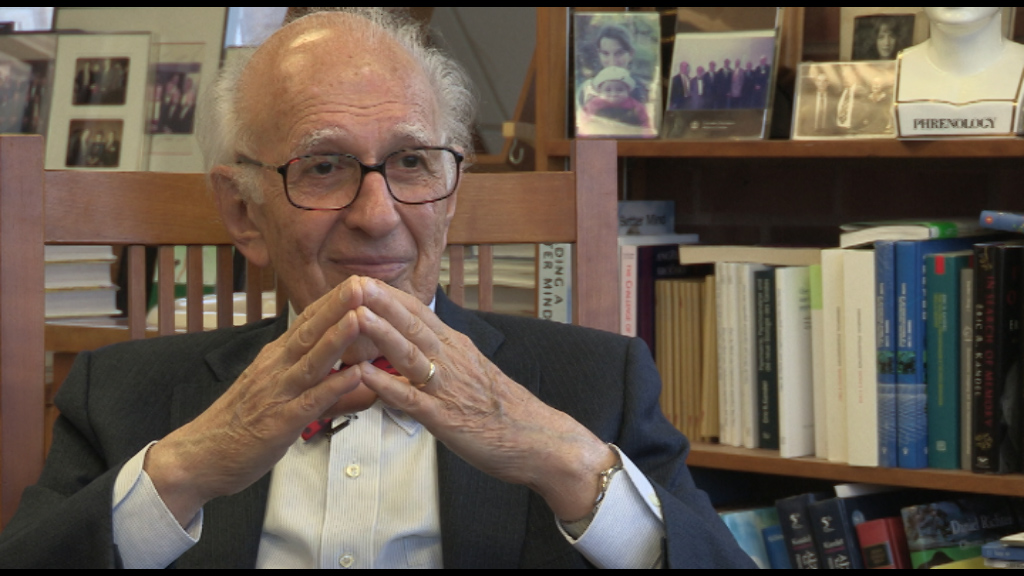

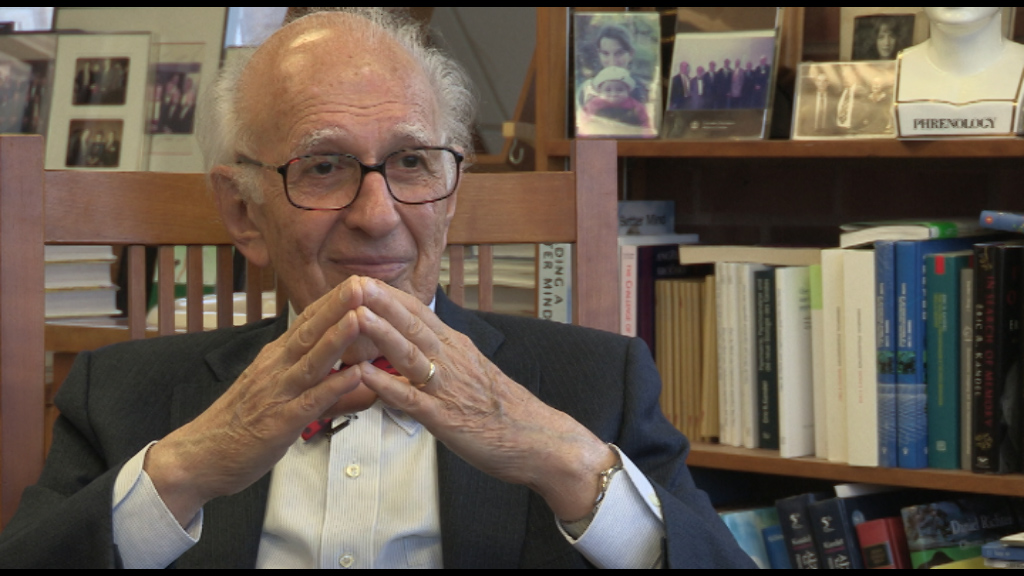

Eric Kandel (b. 1929) is an American neuropsychiatrist. He was a recipient of the 2000 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his research on the physiological basis of memory storage in neurons. He shared the prize with Arvid Carlsson and Paul Greengard. Kandel, who had studied psychoanalysis, wanted to understand how memory works. His mentor, Harry Grundfest, said, 'If you want to understand the brain you're going to have to take a reductionist approach, one cell at a time.' Kandel then studied the neural system of the sea slug Aplysia californica, which has large nerve cells amenable to experimental manipulation and is a member of the simplest group of animals known to be capable of learning. Kandel is a professor of biochemistry and biophysics at the College of Physicians and Surgeons at Columbia University. He is also Senior Investigator in the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. He was the founding director of the Center for Neurobiology and Behavior, which is now the Department of Neuroscience at Columbia University. Kandel's popularized account chronicling his life and research, 'In Search of Memory: The Emergence of a New Science of Mind', was awarded the 2006 Los Angeles Times Book Award for Science and Technology.

Title: How a review inspired a textbook

Listeners: Christopher Sykes

Christopher Sykes is an independent documentary producer who has made a number of films about science and scientists for BBC TV, Channel Four, and PBS.

Tags: Principles of Neural Science, Alden Spencer

Duration: 2 minutes, 19 seconds

Date story recorded: June 2015

Date story went live: 04 May 2016