NEXT STORY

Investigating the biology of post-traumatic stress disorder

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Investigating the biology of post-traumatic stress disorder

RELATED STORIES

The first experiments we did were to see whether or not mice show age-related memory loss. Because one of the interesting things about mice is mice don't show Alzheimer's disease, [spontaneously]. You can put a mutated Alzheimer's gene into it, but on their own they don't show Alzheimer's disease. Do they show age-related memory loss? So we explored that. And we found – this was with Mark Mayford – and we found that mice who live to two years old begin to show a significant decline in memory in middle age, round about one years old, and then it progresses dramatically. And that is PKA-dependent. If you give cyclic AMP or the cyclic AMP dependent protein kinase you can restore that.

More recently we've gone on in two major directions with that. One is we collaborated with Scott Small. Scott Small had found that age-related memory loss seems to start in a different region than Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's disease starts in the entorhinal cortex which is the input in hippocampus. Age-related memory loss starts in the dentate gyrus. So he worked on autopsy specimens, and he took autopsy specimens from people ranging in age from 40 to 90, and who did not have Alzheimer's disease, and he compared dentate gyrus to entorhinal cortex, and he found that there were about 19 to 20 genes that were selectively affected. They either went up or down in a systematic way in age-related fashion in the dentate gyrus and not in the entorhinal cortex.

We focused on one particularly dramatic example, RbAp48 which declined systematically as a function of age. And what's interesting about RbAp48, it's part of the CREB transcription machinery. CREB binds to the CREB-binding protein, which binds to RbAp48, which is a histone acetylase. So it's really the trigger for the gene expression initiated by CREB.

So we went to mice, and we asked the question: when mice age, do they show a decrease in RbAp48, and is it selective to the dentate gyrus? Beautiful decline, absolutely selective we didn't see in other regions of the hippocampus, we didn't see it in the entorhinal cortex, okay? Then we said, what happens if we take an old mouse and restore RbAp48? And we did, it with a tetracycline system so you could, you know, put it back, and then turn it off again. If you restore it, boom, you restore the memory. Turn it off, disappears.

More recently we've begun to collaborate with Gerard Karsenty who has made the interesting discovery that bone is an endocrine gland. It releases a hormone called osteocalcin. And osteocalcin has many functions, including functions of the brain, acts on a number of transmitter systems and affects memory. So he called me up, and we began to collaborate on age-related memory loss. This is Stelios [Kosmidis] in my lab has done this beautifully and he showed stimulation of RbAb48 is very important for age-related memory loss. And as you know, bone mass decreases with age, particularly in women, also in men. Exercise overcomes that, and you exercise an old mouse, you can partially restore age-related memory loss through RbAb48.

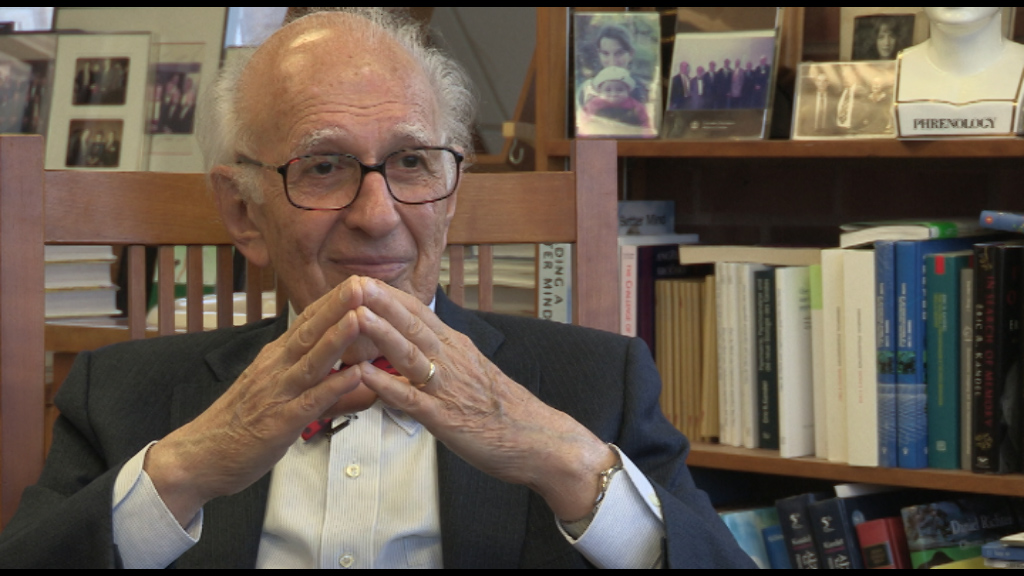

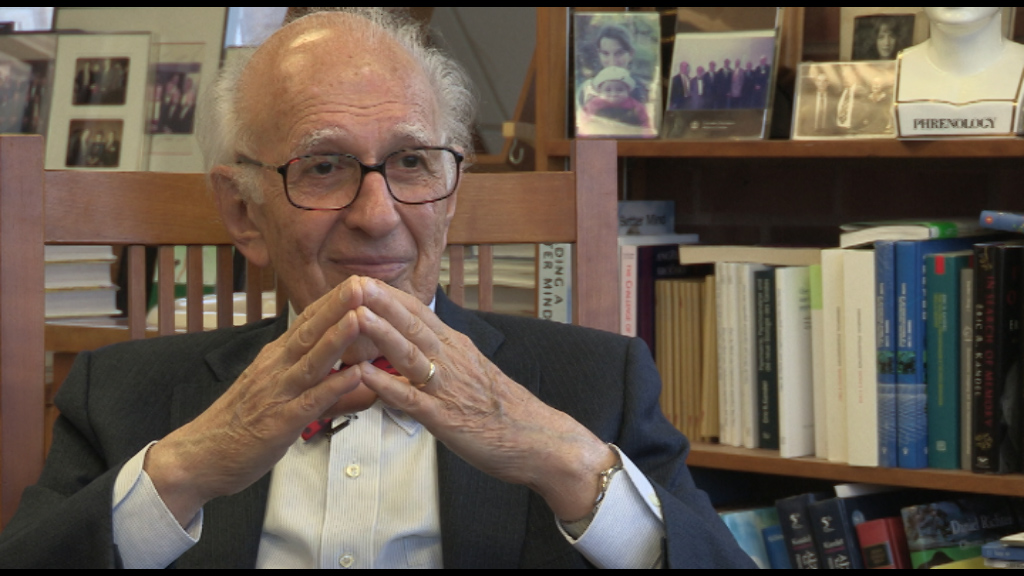

Eric Kandel (b. 1929) is an American neuropsychiatrist. He was a recipient of the 2000 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his research on the physiological basis of memory storage in neurons. He shared the prize with Arvid Carlsson and Paul Greengard. Kandel, who had studied psychoanalysis, wanted to understand how memory works. His mentor, Harry Grundfest, said, 'If you want to understand the brain you're going to have to take a reductionist approach, one cell at a time.' Kandel then studied the neural system of the sea slug Aplysia californica, which has large nerve cells amenable to experimental manipulation and is a member of the simplest group of animals known to be capable of learning. Kandel is a professor of biochemistry and biophysics at the College of Physicians and Surgeons at Columbia University. He is also Senior Investigator in the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. He was the founding director of the Center for Neurobiology and Behavior, which is now the Department of Neuroscience at Columbia University. Kandel's popularized account chronicling his life and research, 'In Search of Memory: The Emergence of a New Science of Mind', was awarded the 2006 Los Angeles Times Book Award for Science and Technology.

Title: Brains, bones and age-related memory loss

Listeners: Christopher Sykes

Christopher Sykes is an independent documentary producer who has made a number of films about science and scientists for BBC TV, Channel Four, and PBS.

Tags: Scott Small, Gerard Karsenty

Duration: 3 minutes, 58 seconds

Date story recorded: June 2015

Date story went live: 04 May 2016