NEXT STORY

'Better search makes people smarter'

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

'Better search makes people smarter'

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 201. Wars and disappointment in the government | 80 | 02:30 | |

| 202. 'The government is a pretty lousy customer' | 79 | 01:47 | |

| 203. My visit to Guantanamo Bay | 82 | 03:43 | |

| 204. The map of knowledge and the map of ignorance | 86 | 03:14 | |

| 205. The 'Cyc' project and why it was flawed | 82 | 02:09 | |

| 206. Freebase – the first free semantic network | 73 | 03:33 | |

| 207. Freebase pioneers semantic search | 70 | 04:29 | |

| 208. 'Better search makes people smarter' | 1 | 78 | 02:00 |

| 209. Emergency breach manoeuvre in a nuclear submarine | 70 | 04:14 | |

| 210. Saying 'left' instead of 'right' in a nuclear submarine | 70 | 02:17 |

So we made this free database that had all kinds of information about astronomy and sports scores and I, of course, thought that the scientific information was going to be the information that people would be most interested in sharing. But actually scientists are pretty bad at sharing information. They sort of hold onto their datasets. It turned out that the information that people were most willing to put in was about pop culture, music. People who were interested in operas would put in: 'This person sang in this opera.' Or architects or movie stars or television shows. So it started building up until it had, you know, knew about billions of entities and relationships between those entities. And we had this idea that an entity had this sort of loose idea of a type, where you would expect to know things about it. So let's take somebody like Arnold Schwarzenegger was an interesting one, because he's a politician, so you expect him to have political affiliations and offices that he's held and he's also a movie star, so you expect him to have movies that he's in and roles that he's played. And he's also actually an athlete and you expect him to have prizes that he's won for being Mr Olympia. And so every entity had different aspects which would create different expectations as to what relationships you would expect to see. And so it was a very flexible system, and then relationships were sort of automatically bidirectional. So if you said, you know, Arnold Schwarzenegger's wife is Maria Shriver it would automatically say, well, Maria Shriver's husband is Arnold Schwarzenegger. So that was the way that it was built up. So we started building it up and then we made it available for free, which was kind of the business model in those days. And sure enough, people started using it for all kinds of things.

The Wikipedia actually started mining it and putting it into Wikipedia articles and we had... but the search engines started using it because they didn't really know much about the things they were searching on. In particular, they didn't know what ads to put on them. So if you were searching for the Washington Redskins, they didn't necessarily know that was a football team in Washington, so they didn't know to put football ads in Washington on that page. And so they had a business problem that we solved for them. So all the search engines started using our database. And it was also had the potential of making search much better. So up till then search was based on keywords. So if I searched for, say, museums of New York, it would search for pages that had the word museum and the phrase New York on it. But if, let's say, you happened to say about the Met, didn't happen to use the word museum on the page. So the Met's exhibits in Manhattan, it didn't really know that Manhattan was in New York or the relationships between exhibits. It didn't know what the Met was. So in order to really do a search, you really wanted to know what these things were and what their relationships were. You wanted to know Manhattan was in New York. And so that would be a kind of semantic search. And so search engines were just beginning to realise they needed that. And so eventually what happened was that we didn't have any business model, but the search engines needed us, so we eventually sold the company to Google.

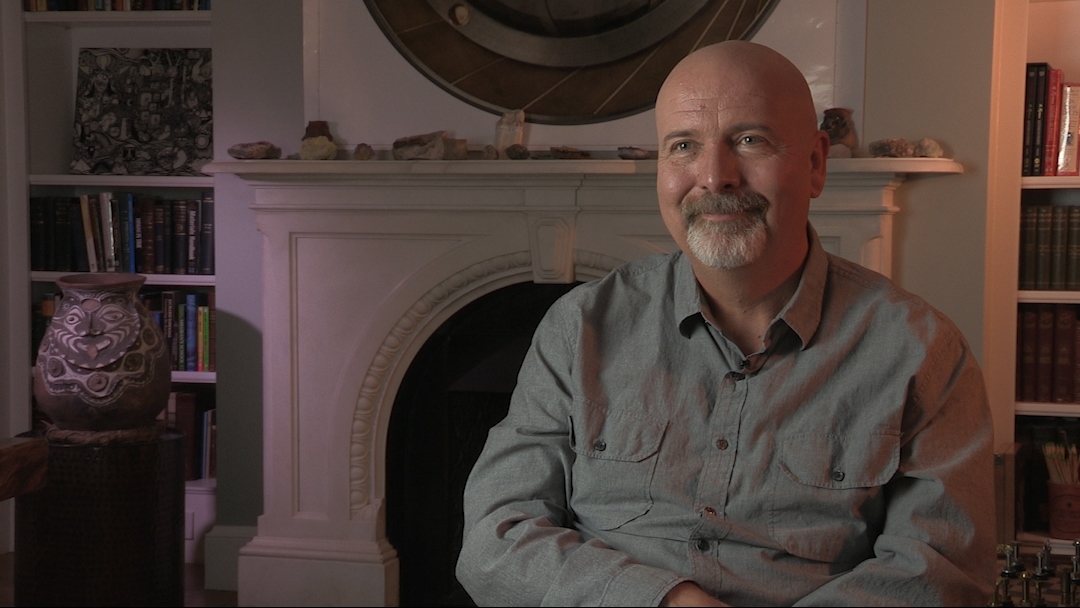

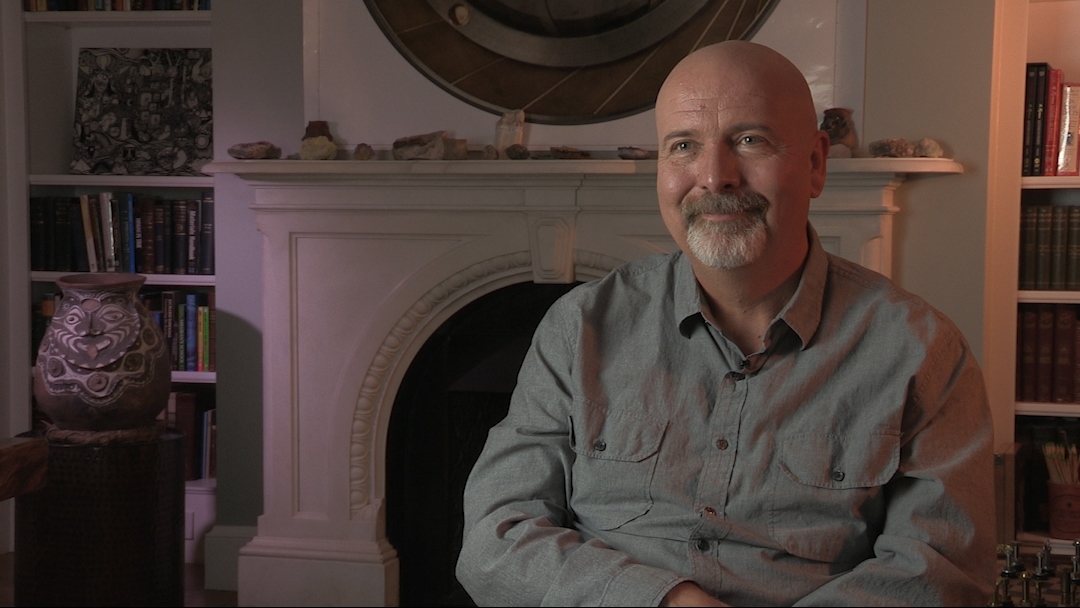

W Daniel Hillis (b. 1956) is an American inventor, scientist, author and engineer. While doing his doctoral work at MIT under artificial intelligence pioneer, Marvin Minsky, he invented the concept of parallel computers, that is now the basis for most supercomputers. He also co-founded the famous parallel computing company, Thinking Machines, in 1983 which marked a new era in computing. In 1996, Hillis left MIT for California, where he spent time leading Disney’s Imagineers. He developed new technologies and business strategies for Disney's theme parks, television, motion pictures, Internet and consumer product businesses. More recently, Hillis co-founded an engineering and design company, Applied Minds, and several start-ups, among them Applied Proteomics in San Diego, MetaWeb Technologies (acquired by Google) in San Francisco, and his current passion, Applied Invention in Cambridge, MA, which 'partners with clients to create innovative products and services'. He holds over 100 US patents, covering parallel computers, disk arrays, forgery prevention methods, and various electronic and mechanical devices (including a 10,000-year mechanical clock), and has recently moved into working on problems in medicine. In recognition of his work Hillis has won many awards, including the Dan David Prize.

Title: Freebase pioneers semantic search

Listeners: Christopher Sykes George Dyson

Christopher Sykes is an independent documentary producer who has made a number of films about science and scientists for BBC TV, Channel Four, and PBS.

Tags: Freebase

Duration: 4 minutes, 29 seconds

Date story recorded: October 2016

Date story went live: 05 July 2017