NEXT STORY

JBS Haldane

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

JBS Haldane

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 21. Comparative anatomy at UCL | 1 | 1001 | 02:01 |

| 22. Peter Medawar: 'He smiles and smiles and is a villain' | 2 | 1614 | 04:23 |

| 23. JBS Haldane | 1 | 1801 | 01:41 |

| 24. JBS Haldane's major work | 1 | 1559 | 01:41 |

| 25. Haldane and the motor car | 1 | 1782 | 02:45 |

| 26. JBS Haldane's trouble with personal relationships | 1668 | 03:43 | |

| 27. Helen Spurway | 1098 | 01:30 | |

| 28. The ethologists: Tinbergen and Lorenz | 1274 | 03:02 | |

| 29. Courtship behaviour in Drosophila | 822 | 04:05 | |

| 30. The idea of sexual selection | 2 | 1014 | 01:22 |

Medawar was actually... he was a new boy at the same time as me. I mean, Watson retired the year I graduated and became a graduate student, and Medawar became Professor of Zoology the year I became a graduate student. He was an immunologist. And to be honest, I'd never heard of him when he was appointed. I remember learning that this person called PB Medawar was going to be our new Professor of Zoology, and I was a first year graduate student with Haldane at that stage. And I remember asking Haldane one evening about, you know, what sort of chap is this Medawar. To which Haldane replied, 'He smiles and smiles and is a villain.' And if you knew Peter Medawar, it was a perfect description, except, of course, that Peter was a great scientist with a passion for the truth. But he... it wasn't fair really, he was not only incredibly intelligent and skilful manually, all the gifts you need to be a great scientist. He was also extraordinarily handsome, I mean, he really was very handsome indeed. He had a beautiful wife, charming children, one just really felt that, you know, too much had been given to one man.

[Q] Niko Tinbergen described him as touched by the gods.

Yes, there was an element, and, of course, as you know, the gods got him, he had a terrible stroke. But Peter was, this curious amalgam, of on the one hand, a man so charming. Another - I've quoted one piece of Shakespeare, let me quote another one: 'He would have men about him that are fat, sleek-headed men, and such that sleep at nights.' He didn't like rows, he liked courtesy, he liked comfort around him. But this is giving a totally false impression of the real Medawar. The real Medawar was a man passionate for the truth... and deeply critical of fudge, of obscurantism, of muddle. He was a lovely man, I mean, I... I want to make it clear that I loved him, and yet, there was a part of Peter, this smoothness, this charm, which one felt was unfair, almost, you know.

I can remember him - my wife and I used to play bridge with Peter every Saturday night, not with Peter and his wife, because his wife didn't like bridge, but with Peter and his mother, and you only had to meet his mother to know where the IQ had come from, she was a very smart old lady. Anyway, not that this has got anything to do with science, but I remember Peter ringing me up one Friday, just checking that Sheila and I were OK for the bridge. I'd just been reading The Times, which we took in those days, and on the front page of The Times was a new honours list. Peter was going to become Sir Peter Medawar. It was breakfast time, I wasn't really awake, and the phone rang and Peter's voice was there, and I said, 'Peter, there's dreadful news in The Times this morning, have you seen it?' To which he replied, 'John, I knew you'd feel like that.' So, you know, there was... Peter wanted to become Sir Peter Medawar. It's ridiculous, how can the crew that give out honours honour a man like that? I mean, it's absurd. I mean, he had honour, but he didn't have to be honoured by that crew. I felt sad about it, and he knew I'd feel sad about it, but we were... the thing I learned from Medawar, scientifically, apart from the importance of clarity and rigour, was that scientific issues ultimately have to be settled by observation or experiment. If there is no observation or experiment that can settle a scientific question, it's not a scientific question. I mean, leave it to the philosophers and let them waste time on it. Ultimately, there has to be a scientific... there has to be an experimental or observational way of doing it. And Peter was very happy, he'd argue for hours, but once one had narrowed a question down to some question of fact that could in principle be done, he didn't really want to discuss it anymore until somebody had done it. And he, of course, had a genius for deciding and designing the experiment that would settle it.

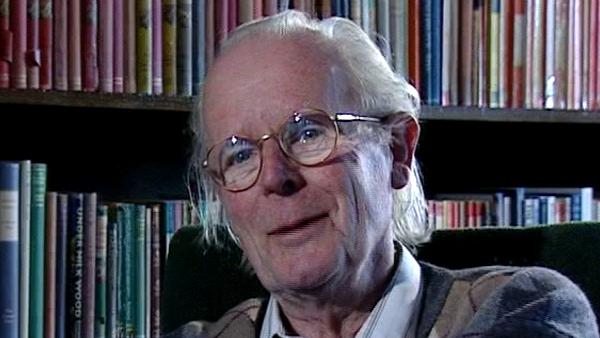

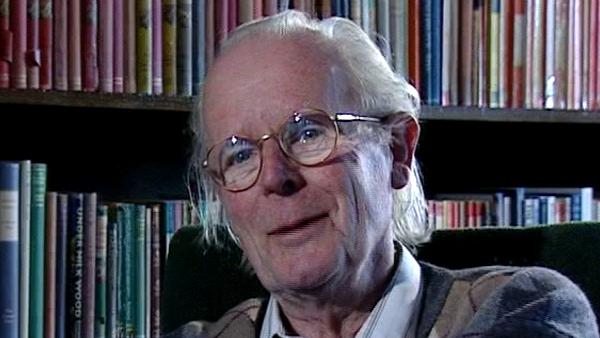

The late British biologist John Maynard Smith (1920-2004) is famous for applying game theory to the study of natural selection. At Eton College, inspired by the work of old Etonian JBS Haldane, Maynard Smith developed an interest in Darwinian evolutionary theory and mathematics. Then he entered University College London (UCL) to study fruit fly genetics under Haldane. In 1973 Maynard Smith formalised a central concept in game theory called the evolutionarily stable strategy (ESS). His ideas, presented in books such as 'Evolution and the Theory of Games', were enormously influential and led to a more rigorous scientific analysis and understanding of interactions between living things.

Title: Peter Medawar: 'He smiles and smiles and is a villain'

Listeners: Richard Dawkins

Richard Dawkins was educated at Oxford University and has taught zoology at the universities of California and Oxford. He is a fellow of New College, Oxford and the Charles Simonyi Professor of the Public Understanding of Science at Oxford University. Dawkins is one of the leading thinkers in modern evolutionary biology. He is also one of the best read and most popular writers on the subject: his books about evolution and science include "The Selfish Gene", "The Extended Phenotype", "The Blind Watchmaker", "River Out of Eden", "Climbing Mount Improbable", and most recently, "Unweaving the Rainbow".

Tags: The Times, Peter Medawar, MDS Watson, JBS Haldane, Nikolaas Tinbergen

Duration: 4 minutes, 24 seconds

Date story recorded: April 1997

Date story went live: 24 January 2008