NEXT STORY

Which is better: parthenogenisis or sexual reproduction?

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Which is better: parthenogenisis or sexual reproduction?

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 61. The University of Sussex: mixing the arts and sciences | 767 | 01:24 | |

| 62. Evolutionary Psychology: The son of Sociobiology | 910 | 01:20 | |

| 63. The problem of sex and group selection | 902 | 02:08 | |

| 64. Which is better: parthenogenisis or sexual reproduction? | 833 | 02:25 | |

| 65. Explaining the maintenance of sex | 835 | 04:56 | |

| 66. The advantage of sex at the individual level | 799 | 03:20 | |

| 67. The engine and the gearbox analogy in sexual reproduction | 616 | 02:06 | |

| 68. The parasite theory, the Red Queen model and Alex Kondrashov | 1118 | 03:19 | |

| 69. The origin of sex | 834 | 01:19 | |

| 70. How bacteria share genes; Streptococcus and... | 570 | 04:38 |

The problem presented itself to me, in the first instance, curiously enough, as a kind of follow-up of my criticisms of Wynne Edwards. You remember that Wynne Edwards had been arguing that certain kinds of behaviour were the result of group selection, and I had been very critical about the possibility that group selection could produce the kinds of results that he was claiming. And then I sort of stopped to think and realised that the conventional view, even within evolutionary genetics - you can even find it in RA Fisher - of sex, was that its presence was because it was good for the population. And the standard work on the subject, I suppose, in those days, was a book called The Evolution of Genetic Systems by Darlington. It's a fascinating book, I mean, full of really good biology and interesting problems, but essentially group selectionist. Sex is to be explained because it is good for the species. And I remember sort of thinking, well, now, it really isn't fair that I should go around bashing Wynne Edwards for his group selection views on behaviour if I'm accepting a group selection explanation for sex. I mean, it really doesn't seem... seem right. And that's what made me start thinking about the problem. And the problem can be... in its stark form can be explained very simply, and it's this; imagine a species in which... and think not of ourselves, where there's parental care, but I tend to think of something like a codfish or something, which doesn't look after its kids - and imagine a gene and mutation causing females to... not to mate, not to go through the process of meiosis and production of a reduced egg, but simply to produce eggs, diploid eggs, genetically identical to themselves, and lay them, without bothering with males, and that those eggs, being genetically identical to the female, would also develop as females. In other words, what we call ameiotic parthenogenesis.

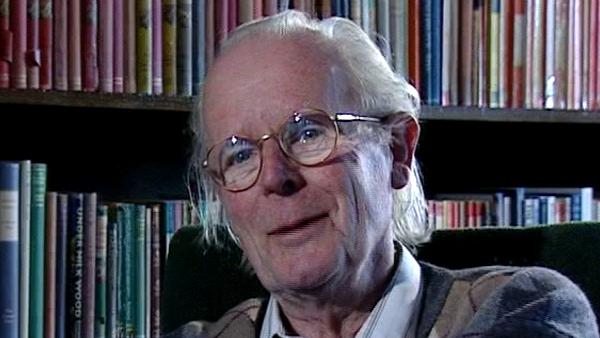

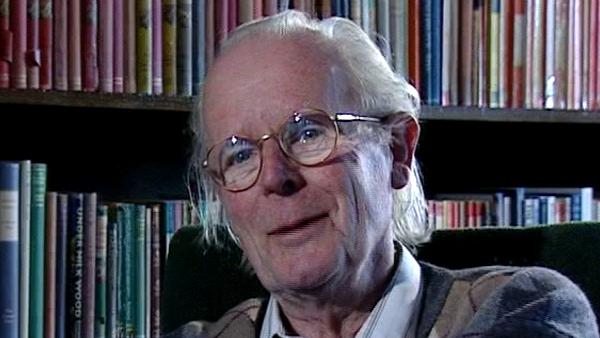

The late British biologist John Maynard Smith (1920-2004) is famous for applying game theory to the study of natural selection. At Eton College, inspired by the work of old Etonian JBS Haldane, Maynard Smith developed an interest in Darwinian evolutionary theory and mathematics. Then he entered University College London (UCL) to study fruit fly genetics under Haldane. In 1973 Maynard Smith formalised a central concept in game theory called the evolutionarily stable strategy (ESS). His ideas, presented in books such as 'Evolution and the Theory of Games', were enormously influential and led to a more rigorous scientific analysis and understanding of interactions between living things.

Title: The problem of sex and group selection

Listeners: Richard Dawkins

Richard Dawkins was educated at Oxford University and has taught zoology at the universities of California and Oxford. He is a fellow of New College, Oxford and the Charles Simonyi Professor of the Public Understanding of Science at Oxford University. Dawkins is one of the leading thinkers in modern evolutionary biology. He is also one of the best read and most popular writers on the subject: his books about evolution and science include "The Selfish Gene", "The Extended Phenotype", "The Blind Watchmaker", "River Out of Eden", "Climbing Mount Improbable", and most recently, "Unweaving the Rainbow".

Tags: The Evolution of Genetic Systems, VC Wynne Edwards, RA Fisher, CD Darlington

Duration: 2 minutes, 9 seconds

Date story recorded: April 1997

Date story went live: 24 January 2008