NEXT STORY

Miss Nobody

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Miss Nobody

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 171. The Crowned-Eagle Ring and the new audience in Poland | 41 | 04:30 | |

| 172. The new audience in Poland | 25 | 03:59 | |

| 173. A Japanese play and the film Nastasia | 114 | 01:30 | |

| 174. Holy Week | 83 | 03:00 | |

| 175. Western interest in Polish films during the Cold War | 33 | 02:24 | |

| 176. Miss Nobody | 37 | 02:07 | |

| 177. Looking for a film topic for the new audience | 26 | 01:54 | |

| 178. With Fire and Sword | 32 | 04:09 | |

| 179. Pan Tadeusz - The Last Raid in Lithuania | 43 | 04:31 | |

| 180. Working on Pan Tadeusz - The Last Raid in Lithuania | 26 | 02:22 |

Sytuacja się totalnie zmieniła i po prostu nagle, w momencie, kiedy runął mur berliński, Europa przestała interesować się, co jest za tym murem. Przecież to był jeden z ważnych momentów zaciekawienia polskim kinem. Polska była krajem, który miał najwięcej swobody, w związku z tym nasze filmy opowiadały o rzeczach, które w innych kinematografiach socjalistycznych, a już w radzieckiej najmniej, w ogóle nie mogły istnieć, a świat wtedy był podzielony na 'zimną wojnę'. I ta 'zimna wojna' nie była tylko trikiem propagandowym z jednej i z drugiej strony, z radzieckiej i z amerykańskiej, tylko była rzeczywistością. Ludzie bali się wojny, zwłaszcza Zachód się bał wojny. Im bardziej Zachód, że tak powiem, się bogacił, im bardziej czuł się pewny siebie, tym bardziej czuł się zagrożony Związkiem Radzieckim, bombą atomową, którą w dużym ilościach wyprodukował Związek Radziecki, pogróżkami Związku Radzieckiego. W związku z tym Francja, Anglia, Niemcy – zwłaszcza Niemcy – interesowali się: a co jest za tym murem? Kto tam mieszka? Co oni myślą? Czego oni chcą? I nasze filmy właśnie o tym mówiły. To było powodem, że nasze filmy, przechodząc na drugą stronę berlińskiego muru, budziły zainteresowanie wszystkich. Wszyscy chcieli zobaczyć. Człowiek z marmuru – a to oni mają jakieś porachunki z partią, jak to jest? Człowiek z żelaza – aha, budzą się, coś będzie, jakieś wydarzenie, co, jakie to są szanse tych wydarzeń. Ale nie tylko polityczne filmy, inne filmy historyczne też miały swoje jakby... swoje echo. Tu nagle się okazało, że nie, nikt nie czeka już na polskie filmy po tamtej stronie, a na takie filmy nikt nie czeka po tej stronie. Muszę powiedzieć, że to był najbardziej bolesny okres w moim życiu. I jeszcze raz spróbowałem spotkać się z widownią. No jeżeli w kinie jest młoda widownia, trzeba zrobić taki film, który by trafił do tej młodej widowni. Jaka to jest młoda widownia? No bardzo szybko Polska upodobniła się do reszty Europy. No kto siedzi w kinie? Od 15 do 25 lat.

The situation changed completely and, quite simply, once the Berlin Wall fell; Europe stopped caring about what was behind that wall. This was an important moment regarding the interest people took in Polish cinema. Poland was the country that had most freedom and so our films were about things that couldn't even exist in other socialist cinematographies, and certainly not in the Soviet cinema. At the time, the world was divided by the Cold War. This Cold War wasn't just a propaganda ploy on either side, both Soviet and American. It was a reality. People feared war, the West especially was afraid of war. The richer the West became, the more self-assured it grew and the more threatened it felt by the Soviet Union, by the atom bomb the Soviets had produced in large quantities and by their threats. Because of this, France, England, Germany, particularly Germany, wanted to know: what's behind that wall? Who lives there? What are they thinking? What do they want? And this is what our films were about. This was why our films aroused everyone's interest once they made it to the other side of the wall. Everyone wanted to see. Man of Marble - so they have a score to settle with the Party? How come? Man of Iron - aha, they're beginning to wake up, something's coming, something's going to happen, what, what are the chances that it's going to work? But it wasn't just political films, other films, historical ones also had an echo. Suddenly it became obvious that no one was waiting for Polish films any longer on the other side nor was anyone waiting for these sorts of films on this side. I have to say that this was the most painful period of my life. I made another attempt to meet my audience. If cinema audiences were young, I needed to make the kind of film that would appeal to a young audience. What is a young audience? Poland had quickly come to resemble the rest of Europe. Who goes to the cinema? Those aged from 15 to 25.

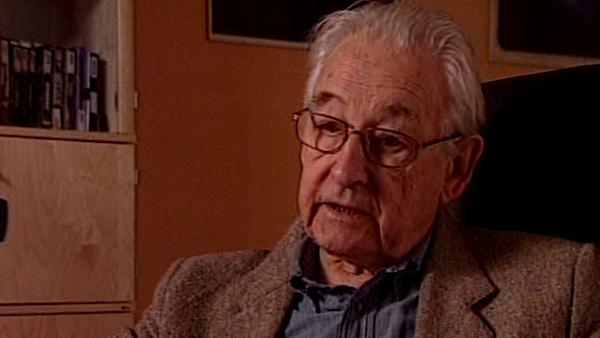

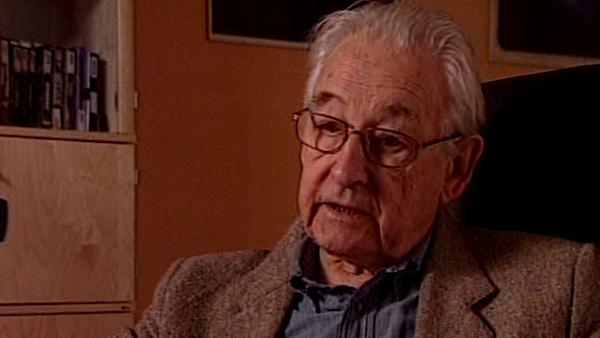

Polish film director Andrzej Wajda (1926-2016) was a towering presence in Polish cinema for six decades. His films, showing the horror of the German occupation of Poland, won awards at Cannes and established his reputation as both story-teller and commentator on Poland's turbulent history. As well as his impressive career in TV and film, he also served on the national Senate from 1989-91.

Title: Western interest in Polish films during the Cold War

Listeners: Jacek Petrycki

Cinematographer Jacek Petrycki was born in Poznań, Poland in 1948. He has worked extensively in Poland and throughout the world. His credits include, for Agniezka Holland, Provincial Actors (1979), Europe, Europe (1990), Shot in the Heart (2001) and Julie Walking Home (2002), for Krysztof Kieslowski numerous short films including Camera Buff (1980) and No End (1985). Other credits include Journey to the Sun (1998), directed by Jesim Ustaoglu, which won the Golden Camera 300 award at the International Film Camera Festival, Shooters (2000) and The Valley (1999), both directed by Dan Reed, Unforgiving (1993) and Betrayed (1995) by Clive Gordon both of which won the BAFTA for best factual photography. Jacek Petrycki is also a teacher and a filmmaker.

Tags: Cold War, Berlin Wall, Europe, Soviet Union, France, Germany, Man of Marble, Man of Iron

Duration: 2 minutes, 24 seconds

Date story recorded: August 2003

Date story went live: 24 January 2008