NEXT STORY

Subjectivity of art: 'Never close your mind to anything'

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Subjectivity of art: 'Never close your mind to anything'

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 21. Passionate affection and wild hatred | 433 | 02:23 | |

| 22. The impact of religion on my life | 615 | 01:16 | |

| 23. Religion and homosexuality: a decade-long abstinence | 449 | 02:51 | |

| 24. Facing prejudice throughout early life | 365 | 03:49 | |

| 25. Sentimental relationships with women | 394 | 02:23 | |

| 26. Refusing female love interest | 544 | 06:00 | |

| 27. Studying at The Courtauld Institute of Art in London | 394 | 05:25 | |

| 28. Postponing my studies to do National Service | 328 | 03:31 | |

| 29. How to be an art critic: 'It's a repeat experience' | 1 | 414 | 07:12 |

| 30. Subjectivity of art: 'Never close your mind to anything' | 378 | 01:25 |

The time factor is essential, and the repeated experience is essential. I… when people would say, how should I look at pictures? My answer is always the same, and it is this: that you go to the National Gallery, for example, and you do not look at every picture. You look at a picture that, in some way, communicates with you. There is something about the picture that makes you pause. And it’s that picture and not these. And that you spend a little time with. And you ask yourself, what is the subject? And then you might ask yourself: what is essentially the subject? Because if it’s pilgrims on the road to Emmaus, it may be the landscape that matters, and the pilgrims are only the excuse for the landscape. Or it may be entirely figurative and have no landscape, and you have no idea through what kind of territory these pilgrims are walking. That’s a beginning. You’re getting a hold on where the painter looks at the story. And then you go and look at something else, which may be Judith and Holofernes, and what is the story of Judith and Holofernes? Is this a great moral story, or is it really fiendishly immoral? Here is a woman who kills a man for not going to bed with her, you know. She thought he was going to seduce her, and he didn’t, but she cuts off his head nevertheless. This is a great Jewish heroine, you know. Think about it. So what element is the painter bringing into this? Is he… does he paint Judith so that she is exultant? Does he paint her as though she is melancholy? Look at the Rubens of Samson and Delilah. And it seems to me that there is, on Delilah’s face, in his picture, an expression of extraordinary melancholy. She’s cutting off the curls and she’s looking at him, and she knows what is about to happen. And she is not entirely convinced that she is doing something that she should.

Look at Rembrandt’s interpretation of it, and you have somebody who is mean and wild, rushing away from the tent, you know, with a backward glance, and curls in her hand. A different way of looking at things. Compare one subject shared by several artists, and each picture will tell you something about the other. Then poke your nose in pictures and look at brushstrokes, because if you look carefully enough, you can see how big the brushes were, and how small. You can see where the brushstroke began and where it ended. You can see whether it’s a heavily loaded brush, with thick paint, and it leaves a little tail behind, an impasto, as we call it. And you lift it away... a little thick point. So you get some idea of the gesture of the painter with the brush.

Look at a shipping picture and it’s full of rigging. How do you think it’s done? Is it done with a very thin brush and very little paint on it? No, it’s not. It’s done with a very long-haired brush with quite a lot of paint on it, and an expert sweep, so that the whole piece of the rigging gets done in one stroke.

Look at the knots in the carpet in Holbein’s Ambassadors. And how do you think they’re done? Well, they’re done with a perfectly normal brush, from which quite a lot of the ends of the hairs have been cut. So it’s short and thick, stumpy. And it carries exactly as much paint as you need for one knot in the carpet. So one knot, one touch of the brush.

Then you see a carpet somewhere else, by Velázquez, perhaps. And it’s impressionist. There are no knots in it. They are loose paint, like this. Slowly, you will get an idea, not only of how different painters paint, but how French painting is different from Italian, and Italian from German. You will get a feeling of how this painting could only have been done in the 17th century, not the 16th, not the 18th. It has to be 17th. And you’ll be soon be going around galleries saying, I don’t know who it’s by, but it’s mid-16th century, and it’s Italian. Then you go and look at the label and you congratulate yourself, and you find that it’s by Parmigianino and the only thing you’ve got wrong is that it the first half of the century and not the middle. But, you know, you’re getting there.

This is how it happens. But it’s a repeat experience. And if you look at the pictures that you looked at the very first time, after you’ve looked at 100 or 200 or 300 other pictures, you go back to them, you will see them with entirely different eyes. And if you do this all the time, you will never stop seeing. You’ll never stop learning. I am constantly… I’m nearly 77, and I am constantly surprised at how much I still learn. And that’s the great joy of looking at pictures, because unless… I mean, there are a great many awful pictures. Jack Vettriano for example. Seen one, you’ve seen the lot. You need never look again. But you look at a painting by Elsheimer half a century ago, and you’ll get something more out of it now.

It’s not a quantifiable discipline, anyway. It’s not a precise discipline. And your response to some painters will be much stronger than to others. Some painters who have great reputations, like Watteau for example. For me, I don’t know where the magic lies. I’ve never seen it. I still can’t see it. Other painters, whom I puzzled over when I was younger, I can now look at with much greater perception. And it’s just a matter of never closing your mind to anything, and…

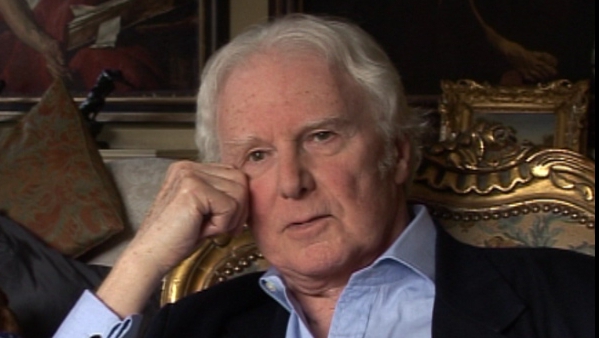

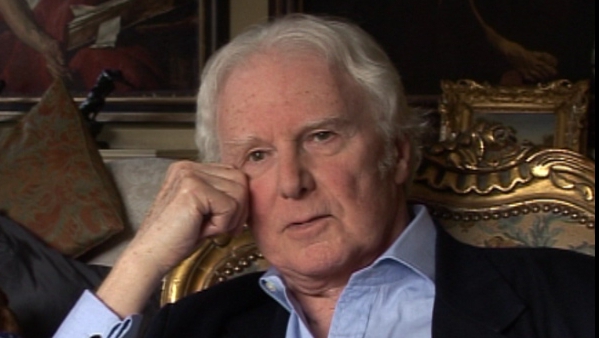

Born in England, Brian Sewell (1931-2015) was considered to be one of Britain’s most prominent and outspoken art critics. He was educated at the Courtauld Institute of Art and subsequently became an art critic for the London Evening Standard; he received numerous awards for his work in journalism. Sewell also presented several television documentaries, including an arts travelogue called The Naked Pilgrim in 2003. He talked candidly about the prejudice he endured because of his sexuality.

Title: How to be an art critic: 'It's a repeat experience'

Listeners: Christopher Sykes

Christopher Sykes is an independent documentary producer who has made a number of films about science and scientists for BBC TV, Channel Four, and PBS.

Tags: National Gallery, Samson and Delilah, The Ambassadors, Impressionism, Holofernes, impasto, Judith, Peter Paul Rubens, Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn, Hans Holbein the Younger, Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez, Parmigianino, Girolamo Francesco Maria Mazzola, Jack Vettriano, Adam Elsheimer

Duration: 7 minutes, 12 seconds

Date story recorded: 2008

Date story went live: 28 June 2012