NEXT STORY

Would you prefer to be Newton or Shakespeare?

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Would you prefer to be Newton or Shakespeare?

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 71. Reasons for religion | 2 | 705 | 01:51 |

| 72. What happens when we die? | 971 | 02:01 | |

| 73. Degrees of plausibility in science | 466 | 00:55 | |

| 74. Truth in science | 2 | 572 | 02:15 |

| 75. Wining the Nobel Prize is a lottery | 1 | 979 | 02:20 |

| 76. Cooperation and rivalry in science | 1 | 573 | 02:34 |

| 77. Would you prefer to be Newton or Shakespeare? | 1 | 956 | 01:30 |

| 78. The effect of individual personalities in science | 600 | 01:20 | |

| 79. What makes science unique? | 769 | 00:56 | |

| 80. The need for strong motivation in choosing a career | 2 | 1042 | 01:52 |

You… you’re obviously all trying to, you know, discover the secrets of nature, or however you like to put it. And, in principle, you’re all supposed to work together and help each other. And a lot of cooperation does go on in science, but there’s necessarily a degree of rivalry. If… first of all, mainly it’s because of reputation, because people want to have the reputation. And unfortunately it’s usually the person who does something first who gets it, not always. Sometimes somebody will do something first and someone will come along and do it very much better. But in general it’s the person who does it first, so there is this element of a race that comes into it. And some people are a lot more competitive than others. Some people are over-competitive, they have what’s called ‘nobelitis’. They look as if they're trying too hard to get a Nobel Prize. That isn’t thought… highly regarded. And… and so you get… get this strange mixture of… of cooperation and… rivalry. You get it to some extent, you know, between the armed forces, which are supposed to cooperate but nevertheless are… have a degree of rivalry. I mean, the… the air force against the navy and the army and so on. There’s always that… that sort of tension there. Or even one regiment against another regiment in the army. So, it’s… it's what you would find in most walks of life, but… but the general public is apt to overstress, I think, the competitive nature and not recognise how much cooperative work there is – people, you know, exchanging ideas and giving each other material and so on. Usually, it’s acknowledged. It’s polite to acknowledge it or make the person a co-author if they’ve done a substantial part… significant part of the work and so on. Very difficult to convey the exact balance. And, unfortunately, it’s got more competitive recently because there are more scientists and there are more good scientists and the techniques are better. And many of them are worthy of support, but because they’ve grown so much, they now need large sums of money, even in biological sciences where they don’t need enormously expensive apparatus like these super colliders, whatever it may be, but they do need apparatus and things. And that’s… that's become an appreciable part, or a noticeable part, of… of the national budget. So… so, you can’t just… can't go on increasing indefinitely. It’s… and… it’s unclear just what level science should be supported because you can argue from different points of view.

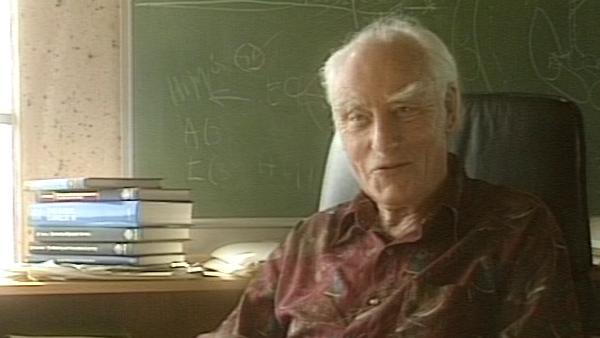

The late Francis Crick, one of Britain's most famous scientists, won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1962. He is best known for his discovery, jointly with James Watson and Maurice Wilkins, of the double helix structure of DNA, though he also made important contributions in understanding the genetic code and was exploring the basis of consciousness in the years leading up to his death in 2004.

Title: Cooperation and rivalry in science

Listeners: Christopher Sykes

Christopher Sykes is an independent documentary producer who has made a number of films about science and scientists for BBC TV, Channel Four, and PBS.

Tags: Nobel Prize

Duration: 2 minutes, 34 seconds

Date story recorded: 1993

Date story went live: 08 January 2010