NEXT STORY

My thesis on electron diffraction in crystals

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

My thesis on electron diffraction in crystals

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Beginning physics at Frankfurt University | 6 | 6510 | 01:48 |

| 2. My father's scientific influence on me | 1 | 2356 | 02:13 |

| 3. Choosing to do theoretical physics | 1836 | 00:59 | |

| 4. 1926: a fortunate time to study with Arnold Sommerfeld | 2135 | 01:28 | |

| 5. Albrecht Unsöld's work on stars | 1359 | 01:42 | |

| 6. Fritz Kirchner's work on the charge of the electron | 1180 | 01:52 | |

| 7. Physics journals at the time and Wilhelm Wien | 1145 | 02:48 | |

| 8. The courses I took at Munich | 1451 | 02:14 | |

| 9. My ideas in wave diffraction theory | 1101 | 03:11 | |

| 10. My thesis on electron diffraction in crystals | 1 | 1119 | 01:51 |

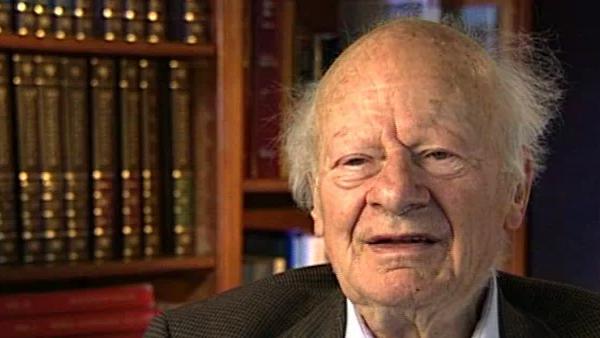

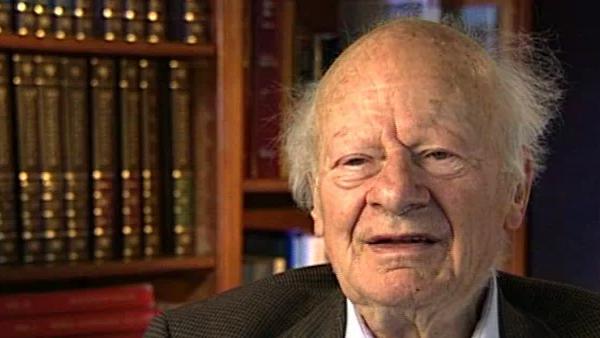

I was again very fortunate because the year before, Davisson and Germer at the Bell laboratories had discovered electron diffraction which directly demonstrated the wave nature of electrons so that... that gave a good basis for Schrödinger for his wave mechanics. And there was one important trouble with Davisson [and] Germer, he got interference patterns, just as you would from waves going through a crystal, but they were never at the right place - and so Sommerfeld gave me a problem already the first semester: Please explain why they are at the wrong angles.

And so I very soon had the idea that electrons, when they enter a metal - the experiments were done with nickel - experience an acceleration which you can't see very well because it is difficult to get electrons out of a metal. And so I... said 'Well, there must be a negative potential in the metal' and it helped that Sommerfeld at the same time was developing his theory of metals which used the Fermi distribution of electrons in the metal, so you had some kinetic energy, so therefore the potential energy must be bigger than the so-called work function, that is the energy which is needed to pull an electron out. And so I said, 'Well there's probably a negative potential, 20 electron volts perhaps, and... that way I could bring the experiments of Davisson and Germer into agreement with wave diffraction theory.

Now about five other people had the same idea at the same time, in fact they were mostly Americans, one was quite a famous man in crystal spectroscopy by the name of Patterson, and Americans never read German papers, so they never paid attention to my paper, but they just quoted each other's papers. Unfortunately I have now adopted the same custom on my own.

The late German-American physicist Hans Bethe once described himself as the H-bomb's midwife. He left Nazi Germany in 1933, after which he helped develop the first atomic bomb, won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1967 for his contribution to the theory of nuclear reactions, advocated tighter controls over nuclear weapons and campaigned vigorously for the peaceful use of nuclear energy.

Title: My ideas in wave diffraction theory

Listeners: Sam Schweber

Silvan Sam Schweber is the Koret Professor of the History of Ideas and Professor of Physics at Brandeis University, and a Faculty Associate in the Department of the History of Science at Harvard University. He is the author of a history of the development of quantum electro mechanics, "QED and the men who made it", and has recently completed a biography of Hans Bethe and the history of nuclear weapons development, "In the Shadow of the Bomb: Oppenheimer, Bethe, and the Moral Responsibility of the Scientist" (Princeton University Press, 2000).

Tags: Bell laboratories, Clinton Davisson, Lester Germer, Erwin Schrödinger

Duration: 3 minutes, 12 seconds

Date story recorded: December 1996

Date story went live: 24 January 2008