NEXT STORY

Advising Stanley Kubrick on 2001: A Space Odyssey

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Advising Stanley Kubrick on 2001: A Space Odyssey

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 91. The impact of the Society of Mind | 1728 | 03:06 | |

| 92. Why the Society of Mind is crucial for understanding... | 1694 | 01:56 | |

| 93. A theory of why evolution is a slow process | 1715 | 03:15 | |

| 94. Biological plausability for the Society of Mind theory | 1560 | 04:04 | |

| 95. Advising Stanley Kubrick on 2001: A Space Odyssey | 2 | 1974 | 02:51 |

| 96. Stanley Kubrick forgets he made Dr Strangelove | 2 | 1994 | 01:38 |

| 97. What was Stanley Kubrick like? | 2 | 2393 | 01:03 |

| 98. Stanley Kubrick scraps the tetrahedron | 1 | 1948 | 02:11 |

| 99. I created part of 2001: A Space Odyssey | 1 | 1805 | 00:46 |

| 100. Warren McCulloch: For whom the world was a stage | 1827 | 04:25 |

What Susumu Ohno pointed out is that... instead of modifying a gene, what if you duplicate it? And I... let’s carry that a little further and say, maybe on rare occasions, instead of duplicating a gene, suppose you duplicate a whole chromosome. There are many plants, for example, in which the entire set of chromosomes got accidentally duplicated. And, some plants’ seeds are just full of chromosomes because this happened many times. Anyway, you see, the point is that... now, if you have two copies of the gene – and preferably on different chromosomes, but not necessarily – now if you mutate one of them, there’s a chance that that could improve the heart without damaging the brain because there’s still the other copy of the gene making the function that works. The chances are it'll be slightly less good because the new gene will be not optimal, but at that point evolution can start off almost anew because now this gene can go this way and make the heart valve even better without hurting the brain. Presumably, this one drops out after a while and this other one can now make you slowly get better at learning or predicting or whatever function of the brain it’s doing, depends where it's expressed or... so that’s... Ohno’s idea. It’s a wonderful point. So, he’s saying that duplication is the most important thing. Optimization is what Darwin talks about – except of course Darwin didn’t know about genes – but he had a sound intuition about something like that. So that’s the big idea and that’s why I think we can assume that the Society of Mind theory is basically correct. How did people get so much smarter than chimpanzees? And how did chimpanzees get so much smarter than monkeys? And how did monkeys get so much smarter than – I forget what – squirrels? And, the big question is... I'm... I’m sure everybody knows that in the end we’re all descended from yeast. 'Cause yeast was the last thing between plants and animals. The... there was a duplication or a diversity operation and these went off and became plants and these became animals and we’re down here somewhere. It’s all part of a wonderful adventure. But the idea is that... if this is true – and it’s hard to see how it could be wrong and Ohno has a whole book showing examples – the best example is if you look at the spinal column where you have... I forget how many vertebrae there are – about 30 – but he traced the origin of the history of the genetics of the different branches of the spinal cord. And there are four or five groups. And in fact, it’s known that where the duplications and divisions happened and you can trace the differences between the nerves that come out of the different spinal segments in terms of the history of the way that the spinal column itself evolved. Anyway, it’s a beautiful story. And that’s another biological – rather than psychological – reason why something like the Society of Mind theory ought to be true, but you don’t see this approach in psychology. Somehow, this kind of thinking really doesn’t appear yet in what’s taught as psychological theories today. I’d like to see more... more thinking about that sort of thing.

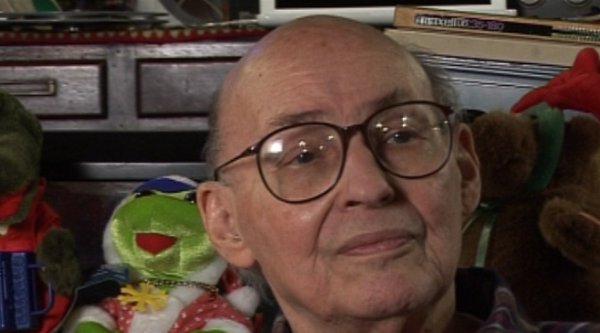

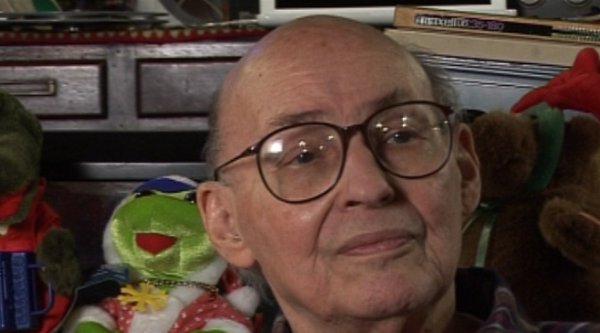

Marvin Minsky (1927-2016) was one of the pioneers of the field of Artificial Intelligence, founding the MIT AI lab in 1970. He also made many contributions to the fields of mathematics, cognitive psychology, robotics, optics and computational linguistics. Since the 1950s, he had been attempting to define and explain human cognition, the ideas of which can be found in his two books, The Emotion Machine and The Society of Mind. His many inventions include the first confocal scanning microscope, the first neural network simulator (SNARC) and the first LOGO 'turtle'.

Title: Biological plausability for the Society of Mind theory

Listeners: Christopher Sykes

Christopher Sykes is a London-based television producer and director who has made a number of documentary films for BBC TV, Channel 4 and PBS.

Tags: Society of Mind, Susumu Ohno, Charles Darwin

Duration: 4 minutes, 5 seconds

Date story recorded: 29-31 Jan 2011

Date story went live: 12 May 2011