NEXT STORY

The summer of 1963

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

The summer of 1963

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 101. Investigating regge poles at MIT | 645 | 04:27 | |

| 102. Quarks, mass shell analysis and the bootstrap | 653 | 01:31 | |

| 103. Giving a course on general ideas about elementary particles | 736 | 01:16 | |

| 104. Parastatistics. Lunch with Bob Serber | 788 | 02:26 | |

| 105. The job situation | 941 | 02:57 | |

| 106. Criticism of Julian Schwinger | 4739 | 01:57 | |

| 107. Woods Hole; working on classified problems | 792 | 01:54 | |

| 108. Anti-ballistic missiles and strategy | 805 | 01:39 | |

| 109. Julian Schwinger | 2914 | 02:22 | |

| 110. The summer of 1963 | 825 | 01:29 |

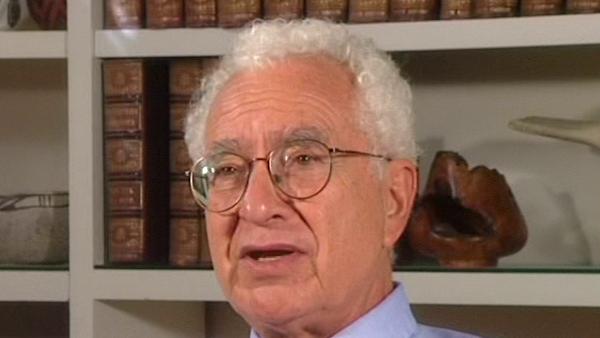

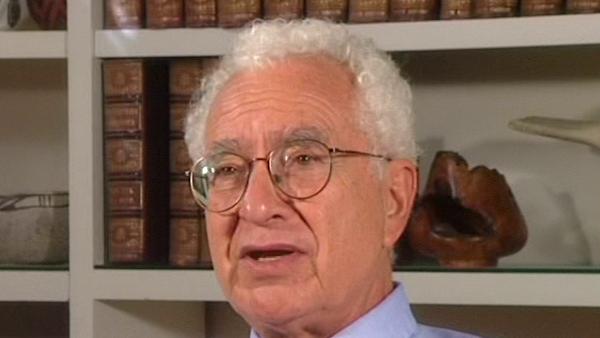

I thought that he promoted elegance above correctness and above honesty, and I was put off by that. And especially after studying with Viki Weisskopf who explained that the important thing was to enlarge our understanding of physics, not to present a lot of shiny mathematical material. It's fine, of course, I have no objection to mathematics being elegant and I've written papers about why elegance is a suitable criterion in the choice of a correct theory and so on and so forth, but it should be used in connection with original and correct material. I was a student in Cambridge when Julian presented some fantastically elaborate mathematical formalism for dealing with quantum field theory: for example quantum electrodynamics. He used some weird looking symbols to avoid Feynman diagrams. Later on, by the way, when I spent that term in Massachusetts the early part of ’63, I rented Julian's house, and I looked all over to see where he kept his hidden Feynman diagrams. There was a locked room, the landlord's locked room, and I assumed that the Feynman diagrams were in there. In any case, to go back, when I was student he presented this fancy scheme. And then he tried not only to show how to do the expansion and perturbation theory, which was basically the same as Feynman's diagrams in some other notation, but he also claimed that he was able to put the whole thing in some sort of closed form, or something that was nearly closed form, and that it was the entire theory. But he had blinded himself with this fancy formalism and didn't notice that he was leaving out all photon-photon scattering. Pauli pointed it out to him. I think that it’s… elegance for its own sake is not the point; the point is elegance in the service of advancing our understanding of science.

New York-born physicist Murray Gell-Mann (1929-2019) was known for his creation of the eightfold way, an ordering system for subatomic particles, comparable to the periodic table. His discovery of the omega-minus particle filled a gap in the system, brought the theory wide acceptance and led to Gell-Mann's winning the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1969.

Title: Julian Schwinger

Listeners: Geoffrey West

Geoffrey West is a Staff Member, Fellow, and Program Manager for High Energy Physics at Los Alamos National Laboratory. He is also a member of The Santa Fe Institute. He is a native of England and was educated at Cambridge University (B.A. 1961). He received his Ph.D. from Stanford University in 1966 followed by post-doctoral appointments at Cornell and Harvard Universities. He returned to Stanford as a faculty member in 1970. He left to build and lead the Theoretical High Energy Physics Group at Los Alamos. He has numerous scientific publications including the editing of three books. His primary interest has been in fundamental questions in Physics, especially those concerning the elementary particles and their interactions. His long-term fascination in general scaling phenomena grew out of his work on scaling in quantum chromodynamics and the unification of all forces of nature. In 1996 this evolved into the highly productive collaboration with James Brown and Brian Enquist on the origin of allometric scaling laws in biology and the development of realistic quantitative models that analyse the influence of size on the structural and functional design of organisms.

Tags: Cambridge MA, Massachusetts, Victor Weisskopf, Julian Schwinger, Wolfgang Pauli

Duration: 2 minutes, 23 seconds

Date story recorded: October 1997

Date story went live: 24 January 2008