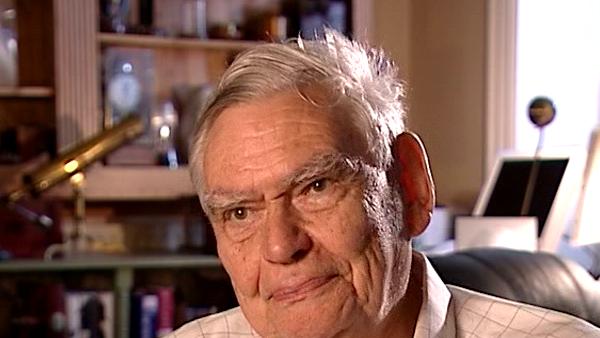

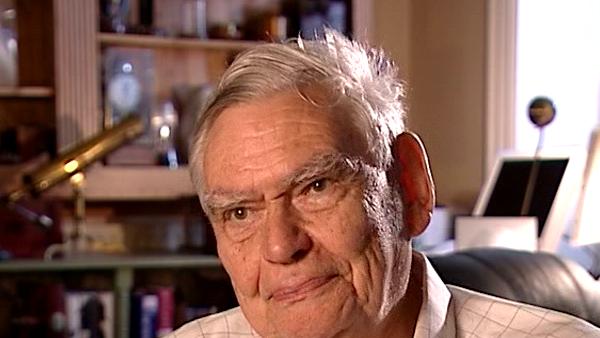

Frank Oppenheimer, I think is a very great man. He was the brother of Robert Oppenheimer who did the Alamos project for the atom bomb, incredibly dramatic stuff applying recent discoveries of physics, Einstein’s equation, potentially to blow up the world and he had to handle this amazing moral problem, warn the American president of the results of building the bomb, worrying that the Germans were in there also trying to build a bomb and in some ways their physics was ahead of everybody else in the world in this way, because they did fusion, I believe, for the first time. So, this is a sort of extraordinary episode in world history and Frank was involved in that with his brother, Robert, very much so. Then at the end of the war, I think the American government pilloried the Oppenheimer family, certainly Robert, thinking that he might even be a spy, as I understand it. They lost faith in him although he was a total genius and totally loyal, the thing was a nonsense really. So that Frank inherited all this and was appalled by the lack of understanding of science both by, I think, the government in America, but certainly by the military and by the public so he decided to set up a science centre which he call the Exploratorium in San Francisco, really to educate subliminally, if you like, the American public in what science is all about and both its potential rewards but also its dangers and, of course, any tool can be dangerous if you’ve got a screwdriver or a chisel, you can hurt yourself, any tool, anything that’s effective can be turned to ill. So I think his feeling was that if you got people to absorb notions of science, the standards of science, the way science works, that it would improve the moral understanding and ability to make the right decision as well as actually improving technology and efficiency and therefore wealth, if you like. It all came together, and I think he felt this could be a resource for schools, a resource for poor people as well as rich, and it was a wonderful dream and he set this thing going. I think it was in 1969 and it’s been an enormous success. It’s still there in San Francisco, it looks a bit like the back of an old garage, it’s not grand, it’s not posh, which I personally think adds enormously to it, a bit of controversy, of course, about the- but I think he was right, entirely right. His idea spread all over the world and changed, mutated, and in a way I think got diluted. I think that most of the science centres that have started since Frank are actually nothing like as good as they should be, in my humble opinion. It’s lost that back-of-a-garage feeling of improvisation, initiative, letting people do things for themselves, make mistakes, learn from their own mistakes without laughing at them, this sort of thing, and he had this wonderful spirit which I’m afraid hasn’t quite spread the way it might have done and I think this is true in this country, England. I actually was instrumental in starting Exploratory, a syllable drop from Exploritorium, I think ten years after he started his. We tried to do exactly the same thing, to make it informal, not terribly grand but it’s got much too grand, in my opinion.