NEXT STORY

Being in the right place at the right time

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Being in the right place at the right time

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 51. The unconscious mind | 255 | 03:20 | |

| 52. Death in my family | 239 | 03:56 | |

| 53. 'If I could be the master over disease' | 183 | 02:44 | |

| 54. Learning I have prostate cancer | 335 | 04:49 | |

| 55. Facing death | 374 | 02:49 | |

| 56. How to prevent a surgical disaster | 227 | 01:36 | |

| 57. First: stay calm! | 216 | 04:13 | |

| 58. Being in the right place at the right time | 185 | 04:25 | |

| 59. Supernatural or just coincidence? | 260 | 03:28 | |

| 60. Ageing is an art | 1 | 282 | 03:29 |

So, in these situations that I had, I can think of three, in those situations, my primary motive was to keep everybody else calm, so I had to keep myself calm, even if I wasn't calm. And I also know it wasn't going to last long, because either I was going to get hold of this bleeder and control it without injuring other organs, or I wasn't. So, it wasn't going to last long, and I had all this background experience. And I had seen my professors in trouble, too. That's another great thing about a surgical programme that you don't hear much about. One of the great virtues of training in the best academic place you can, is you see the best surgeons in the country get into terrible trouble. You see them make terrible errors of judgement and have to compensate for that. You see them suddenly facing a torrent of blood. You see them hearing an anaesthesiologist suddenly announce, this patient can't tolerate much more. You've got to get this thing done. You know, all this. And you see that they always get out of it. And a true tragic ending is exquisitely rare. So, all those things give you strength, but I think, again, of all of them, it's the necessity to remain calm for the sake of others, because you're the boss. I've been with surgeons during my training years when they fell apart.

I was with the ageing chief of urology… a person who had been a great technical surgeon in his earlier days, but shouldn't have been operating, when he put a clamp… he was taking out a kidney. He put a clamp on the main artery to the kidney, the renal artery, which had so much arteriosclerosis in it that it cracked like a pipe, and all of a sudden, this represents about a quarter of the cardiac output, came zooming out into the air. And he completely lost control of himself, and I was the second assistant, I was an intern. The first assistant was the chief resident, who managed to keep a cool head. And the way we got control of that situation was extraordinary. It became necessary to open the chest and get the major blood vessel, the aorta, put a clamp on that to cut down the blood going through the renal artery, and then eventually it tied off and everything was okay. But we had lost a massive amount of blood by then. The anaesthesiologist had two pints of blood, you know, he's pumping one with each hand, and then they put more up, and then… so when you see people get out of situations like this, it also tells your conscious mind and unconscious mind, you're going to do it, you're going to get out.

But there is something about the necessity to stay calm, or you know everything's going to fail. So those have been the things that have saved me during those times. I once… I was very interested in the spleen, and there was a point in the 60s when splenectomies were being done for many, many patients with Hodgkin's Disease. And it had to do with the method the radiologists were using, therapeutic radiologists, to calculate how much disease was in the body. And so many of these people, with relatively early stage Hodgkin's, were undergoing a splenectomy. And I got to be really, really good at getting a spleen out with minimal derangement of anything around it.

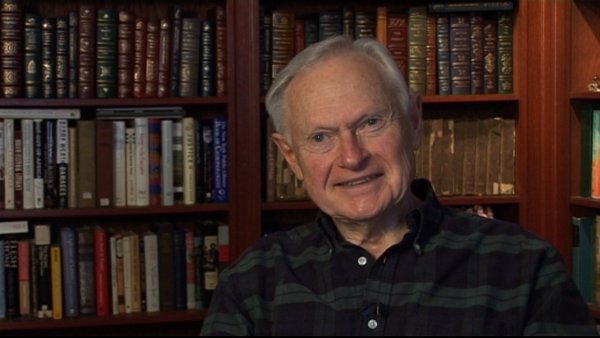

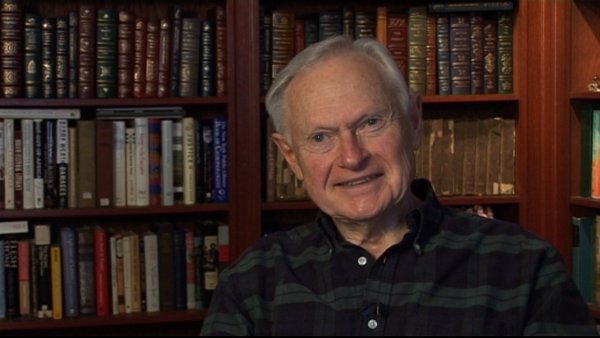

Sherwin Nuland (1930-2014) was an American surgeon and author who taught bioethics, the history of medicine, and medicine at the Yale University School of Medicine. He wrote the book How We Die which made The New York Times bestseller list and won the National Book Award. He also wrote about his own painful coming of age as a son of immigrants in Lost in America: A Journey with My Father. He used to write for The New Yorker, The New York Times, Time, and the New York Review of Books.

Title: First: stay calm!

Listeners: Christopher Sykes

Christopher Sykes is a London-based television producer and director who has made a number of documentary films for BBC TV, Channel 4 and PBS.

Tags: 1960s

Duration: 4 minutes, 13 seconds

Date story recorded: January 2011

Date story went live: 04 November 2011