NEXT STORY

My parents did not agree with my teachers' view of the Nazis

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

My parents did not agree with my teachers' view of the Nazis

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Early childhood recollections about music | 1726 | 02:49 | |

| 2. My father's conditions when I wanted to give up the piano | 460 | 05:34 | |

| 3. My parents did not agree with my teachers' view of the Nazis | 574 | 03:56 | |

| 4. Being drafted at fifteen | 537 | 03:48 | |

| 5. Walking home at the end of the war | 369 | 02:05 | |

| 6. Choosing between music and science | 434 | 01:06 | |

| 7. Going to university and building a seismograph | 334 | 04:11 | |

| 8. Göttingen University and some of its famous professors | 462 | 03:29 | |

| 9. My thesis: 'The specific heat of heavy water' | 412 | 02:50 | |

| 10. Building an adiabatic calorimeter | 304 | 03:21 |

I got real, formal lessons.

[Q] Also your brother, or...?

My brother had already before me, so we played the piano, four hands. And I remember there were concerts for the pupils, for the students, to show what they had learnt, so that we often played four hands. And I really took it very seriously and there was a general assumption that I would become a musician too.

[Q] Already at that time or more a posteriori?

More a little later, because apparently I didn't do very well with my teacher at that time and I remember when I was nine I told my father, 'I don't want to practice any more'.

[Q] You mean music teacher?

Music, yes. I told him the other children have much more time to play and I have to practice. Well my father was not of that opinion, that I had too little time to play around, but he said, 'Of course, if you don't want to play piano you don't need to, but the time you practice you have to use for other useful things. You can read or whatever you want to do, and there are two conditions. The one condition is that have to use the time for...'

[Q] Avoiding hanging around?

Yes, avoiding hanging around. That's very ‒ or playing around. 'You have to do something which is useful. And the other condition is, you are not allowed to play because I don't want you to just, to...'

[Q] Herumklimpern...

Yes. And so I thought both conditions were easy to fulfil. But the most difficult condition turned out to be the latter one, namely not to be allowed to play. So I started to play secretly when my father had left, and it took me only a few months and I practised. And I know still it was the Schubert Arpeggione Sonata, which is difficult for the cello, but my father was a cellist by the way... which is difficult for the cello but not so difficult for the piano. So, at his birthday I...

[Q] Which year?

Oh, I was about ten years old then...

[Q] In 1937?

Nine or ten years, must be...

[Q] 1937?

'36 or, I think it was before '37, before I came to the Gymnasium. But I told him, 'My birthday present is that I play the Arpeggione Sonata with you'. My father laughed at me and said, 'You do that... you are too unexperienced for that'. Well, we sit down, and my father was impressed, and then he got me a good teacher. It was a Professor of the Music Academy of Cologne who was released by the Nazis, he was not in favour of the system, and so he gave lessons...

[Q] Private?

Private lessons. I still remember that when I entered, it was a big room, all the music's notes were lying around, it was not very well...

[Q] A little bit chaotic...

Yes, it was chaotic. And he saw me coming in and say, 'Sit down in the corner, I will play something to you'. And he played a piece of... Hindemith?

[Q] Hmm... at that time? Very modern.

Oh yes, Hindemith was forbidden, this modern music was not allowed by the Nazis but he played of course... and he played a... well I don't remember...

[Q] Was it a piano piece or just the piano part out of the orchestra?

No. It was a piano piece. And, so I... he said, 'Which do you like more?' And I say, 'The classical'. 'Well', he said, 'yes, but be sure that this is a very good composer and you will later like it too'. Then I got wonderful lessons and very soon my father took me away and say, 'Look, I watched it last week, you played every day five hours, you neglect your school work and you must not overdo...' But that was a time I really got into...

[Q] Enthusiastic, into music...

Yes, and I played little concerts already with the orchestra.

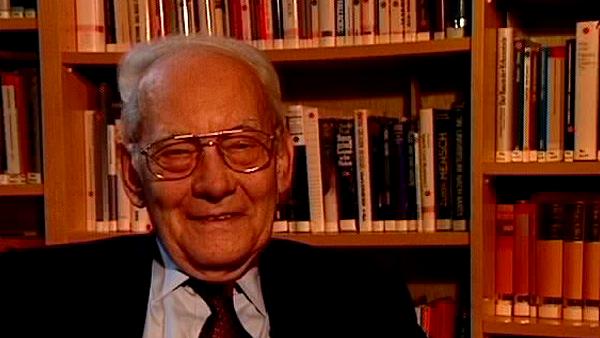

Nobel Prize winning German biophysical chemist, Manfred Eigen (1927-2019), was best known for his work on fast chemical reactions and his development of ways to accurately measure these reactions down to the nearest billionth of a second. He published over 100 papers with topics ranging from hydrogen bridges of nucleic acids to the storage of information in the central nervous system.

Title: My father's conditions when I wanted to give up the piano

Listeners: Ruthild Winkler-Oswatitch

Ruthild Winkler-Oswatitsch is the eldest daughter of the Austrian physicist Klaus Osatitsch, an internationally renowned expert in gas dynamics, and his wife Hedwig Oswatitsch-Klabinus. She was born in the German university town of Göttingen where her father worked at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Aerodynamics under Ludwig Prandtl. After World War II she was educated in Stockholm, Sweden, where her father was then a research scientist and lecturer at the Royal Institute of Technology.

In 1961 Ruthild Winkler-Oswatitsch enrolled in Chemistry at the Technical University of Vienna where she received her PhD in 1969 with a dissertation on "Fast complex reactions of alkali ions with biological membrane carriers". The experimental work for her thesis was carried out at the Max Planck Institute for Physical Chemistry in Göttingen under Manfred Eigen.

From 1971 to the present Ruthild Winkler-Oswatitsch has been working as a research scientist at the Max Planck Institute in Göttingen in the Department of Chemical Kinetics which is headed by Manfred Eigen. Her interest was first focused on an application of relaxation techniques to the study of fast biological reactions. Thereafter, she engaged in theoretical studies on molecular evolution and developed game models for representing the underlying chemical proceses. Together with Manfred Eigen she wrote the widely noted book, "Laws of the Game" (Alfred A. Knopf Inc. 1981 and Princeton University Press, 1993). Her more recent studies were concerned with comparative sequence analysis of nucleic acids in order to find out the age of the genetic code and the time course of the early evolution of life. For the last decade she has been successfully establishing industrial applications in the field of evolutionary biotechnology.

Tags: piano, cello, Sonata in A minor for Arpeggione and Piano, Arpeggione Sonata, Nazi, Music Academic of Cologne, Cologne University of Music, Franz Peter Schubert, Ernst Eigen, Paul Hindemith

Duration: 5 minutes, 34 seconds

Date story recorded: July 1997

Date story went live: 24 January 2008