NEXT STORY

The fitness landscape

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

The fitness landscape

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 61. Extending Darwinian theory to molecules | 160 | 01:31 | |

| 62. The difference between my theory and classical genetic theory | 229 | 02:31 | |

| 63. The fitness landscape | 233 | 02:18 | |

| 64. The complexity of a sequence of nucleotides | 124 | 03:37 | |

| 65. Population and mutation | 120 | 01:22 | |

| 66. The progress of evolution | 124 | 02:47 | |

| 67. Finding a ridge in sequence space | 110 | 01:25 | |

| 68. Low and high dimensional landscapes | 117 | 02:47 | |

| 69. Peter Schuster's concept of sequence space and shape space | 134 | 04:34 | |

| 70. The space of mutants | 110 | 01:27 |

Take a human population. How would I differ from any other in that population? Could I quantify that? Could I say the difference between me and you or somebody else can be expressed by certain numbers? No we can't. In molecules we can. We can look at single mutants. In other words, we write down an equation for every single mutant regardless whether it is a fit one or whether it is a deleterious one. Each mutant comes into the theory with the same right so there is no preferred wild type. If you look at classical genetic theory, the emphasis was always on the wild type. Mutation was a perturbation term, which certainly was there and people know that not all species are genetically exactly identical, but in mathematics you couldn't specify anything and here you can do that quantitatively. You can immediately say, 'If this is the centre of gravity of the distribution, there will be the one error mutants... will be more frequent than the two error...', and you can write down the Poissonian distribution for those mutants now. So you can come up with a set of equations which finally make up the quasispecies. The wild type is somehow the centre of gravity in the quasispecies. It's not a special type in it. It sometimes even might be not the fittest type in the population, but being just in the centre means that it is somehow a consensus sequence of the total distribution. And this leads to the concept of the quasispecies, which was absent in the classical theory. It also leads to the concept of the error threshold. You wouldn't get the error threshold... error threshold is not simply the length of the sequence and the... it depends on the fitness of each sequence which is weighted in this error threshold.

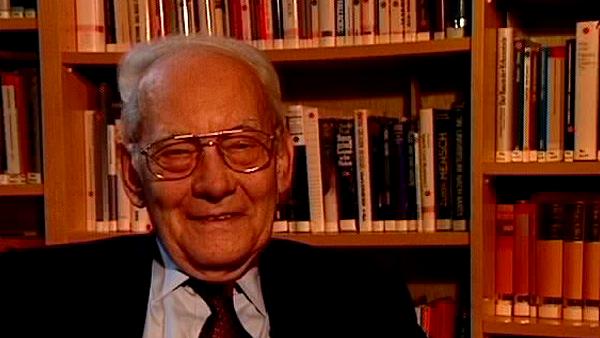

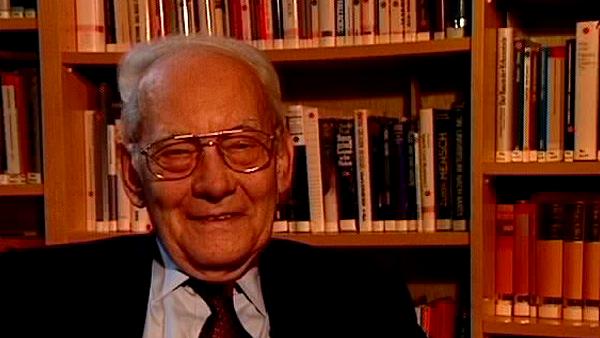

Nobel Prize winning German biophysical chemist, Manfred Eigen (1927-2019), was best known for his work on fast chemical reactions and his development of ways to accurately measure these reactions down to the nearest billionth of a second. He published over 100 papers with topics ranging from hydrogen bridges of nucleic acids to the storage of information in the central nervous system.

Title: The difference between my theory and classical genetic theory

Listeners: Ruthild Winkler-Oswatitch

Ruthild Winkler-Oswatitsch is the eldest daughter of the Austrian physicist Klaus Osatitsch, an internationally renowned expert in gas dynamics, and his wife Hedwig Oswatitsch-Klabinus. She was born in the German university town of Göttingen where her father worked at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Aerodynamics under Ludwig Prandtl. After World War II she was educated in Stockholm, Sweden, where her father was then a research scientist and lecturer at the Royal Institute of Technology.

In 1961 Ruthild Winkler-Oswatitsch enrolled in Chemistry at the Technical University of Vienna where she received her PhD in 1969 with a dissertation on "Fast complex reactions of alkali ions with biological membrane carriers". The experimental work for her thesis was carried out at the Max Planck Institute for Physical Chemistry in Göttingen under Manfred Eigen.

From 1971 to the present Ruthild Winkler-Oswatitsch has been working as a research scientist at the Max Planck Institute in Göttingen in the Department of Chemical Kinetics which is headed by Manfred Eigen. Her interest was first focused on an application of relaxation techniques to the study of fast biological reactions. Thereafter, she engaged in theoretical studies on molecular evolution and developed game models for representing the underlying chemical proceses. Together with Manfred Eigen she wrote the widely noted book, "Laws of the Game" (Alfred A. Knopf Inc. 1981 and Princeton University Press, 1993). Her more recent studies were concerned with comparative sequence analysis of nucleic acids in order to find out the age of the genetic code and the time course of the early evolution of life. For the last decade she has been successfully establishing industrial applications in the field of evolutionary biotechnology.

Tags: quasispecies, mutation, mutant, perturbation, error threshold, wild type

Duration: 2 minutes, 32 seconds

Date story recorded: July 1997

Date story went live: 24 January 2008