NEXT STORY

Why birds are a good starting point in biology

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Why birds are a good starting point in biology

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 21. A few words about the collections | 209 | 01:53 | |

| 22. Bringing the collections together | 188 | 03:58 | |

| 23. Arriving in New York | 1 | 370 | 00:49 |

| 24. Getting married, having children and moving house | 1 | 320 | 01:44 |

| 25. The pros and cons of living in Tenafly, New Jersey | 253 | 01:25 | |

| 26. Geographical species variation in birds | 280 | 01:58 | |

| 27. Lucky accidents that led to fame | 354 | 04:08 | |

| 28. Systematics and the Origin of the Species | 423 | 05:16 | |

| 29. Putting my knowledge to good use | 267 | 02:32 | |

| 30. Why birds are a good starting point in biology | 1 | 348 | 00:38 |

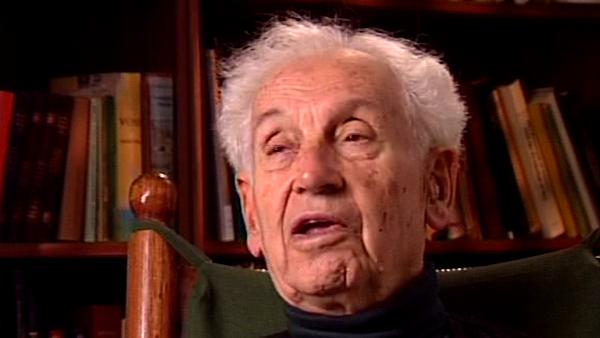

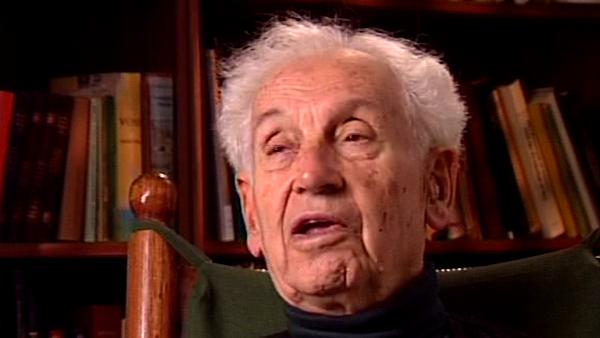

I have been asked in later years quite often how I could have, in such a short time, write [sic] this book that is so rich in information and detail. Well, to begin with I, at that time, was a person of… with an extraordinary memory, I also was a voracious reader of the literature. The American Museum [of Natural History] had a wonderful system that on Tuesday afternoon, every week, all the issues of the new journals that had come during the preceding week were laid out on a table and the staff could look at it and could put in a bid for getting that issue at the next week or week following. So I knew not only the literature on birds, but all the other vertebrates, I read the insect literature, I read the literature on marine invertebrates, I read geology, I read [unclear]… I had an enormous knowledge and I, apparently, more or less wrote the book off the top of my head with all that knowledge. And… the… remarkable thing was that, of course, my findings fitted perfectly well what the people worked on butterflies had found, what the people working on snails had found… it didn’t work so well on some… some other groups, but it was a… a spur to start working along new directions which people hadn’t done up to that time. Even in my own field in ornithology, most of the American ornithologists were still what we referred to as typologists; they described species as such entities and if there was a little difference among species they made it a new genus. And in my book, for instance, I make a list of 37 genera of American birds that were recognized as good genera in the official list of North American birds, published by the American Ornithologists’ Union. Well, the official committee paid no attention to that at all, but in the course of time, now, so far as I know, all these 37 names that I said were not really valid, they all have been sunk into the synonymy, and a much more natural system has been adopted.

The late German-American biologist Ernst Mayr (1904-2005) was a leading light in the field of evolutionary biology, gaining a PhD at the age of 21. He was also a tropical explorer and ornithologist who undertook an expedition to New Guinea and collected several thousand bird skins. In 1931 he accepted a curatorial position at the American Museum of Natural History. During his time at the museum, aged 37, he published his seminal work 'Systematics and Origin of the Species' which integrated the theories of Darwin and Mendel and is considered one of his greatest works.

Title: Putting my knowledge to good use

Listeners: Walter J. Bock

Walter J. Bock is Professor of Evolutionary Biology at Columbia University. He received his B.Sc. from Cornell and his M.A. and Ph.D. from Harvard. His research lies in the areas of organismal and evolutionary biology, with a special emphasis on functional and evolutionary morphology of the skeleto-muscular system, specifically the feeding apparatus of birds.

Tags: Systematics and the Origin of the Species, American Museum of Natural History, American Ornithologists' Union, North America

Duration: 2 minutes, 33 seconds

Date story recorded: October 1997

Date story went live: 24 January 2008