NEXT STORY

The influence of Japanese theatre on The Devils

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

The influence of Japanese theatre on The Devils

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 191. New culture | 29 | 02:52 | |

| 192. Hatful of Rain | 22 | 04:22 | |

| 193. Zbigniew Cybulski in the theatre | 58 | 05:02 | |

| 194. Subsequent theatre plays | 16 | 01:48 | |

| 195. A lesson in directing from Tadeusz Łomnicki | 33 | 04:19 | |

| 196. The Wedding in theatre | 20 | 01:16 | |

| 197. Dostoyevsky's The Devils | 57 | 02:24 | |

| 198. The Devils and the new nationalists | 50 | 03:12 | |

| 199. Dostoyevsky's prompts | 39 | 02:56 | |

| 200. The influence of Japanese theatre on The Devils | 41 | 03:57 |

Z jednej strony miałem adaptację Alberta Camusa, no ale Albert Camus wzorem francuskich autorów po prostu przeniósł wszystko do salonu i zrobił z tego salonową sztukę. A mnie się wydawało, że Dostojewskiego sztuka to jest gdzieś... nie ma ścian, tylko wszystko jest na jakimś skrzyżowaniu, na takim miejscu, gdzie hula wiatr. Zresztą bardzo piękne motto jest wzięte z Puszkina do Biesów, które mówi o tym... o takich zagubionych saniach, gdzie pędzą konie w zadymce śnieżnej i tylko jakieś głosy, że tak powiem słychać, jakichś diabłów, jakiegoś złego ducha, który ściga, że tak powiem, te sanie. No to było dobre motto. Ja to zrozumiałem, że Dostojewski daje mi do zrozumienia, że chciałby takie przedstawienie mieć. Biesy były wystawione za życia Dostojewskiego. W każdym bądź razie była zrobiona adaptacja i bardzo ciekawy był list Dostojewskiego do pani Oboleńskiej, która pracowała nad tą adaptacją. Dostojewski był sceptyczny. Uważał, że teatr jest czym innym, a proza jest czym innym, że to się nie da jednego z drugim ożenić, chyba żeby pani zrobiła daleko idące odstępstwa. To też dla mnie było wskazówką, że ja nie mogę przenosić na ekran powieści Biesy, tylko z tej powieści muszę wydobyć to, co mi daje szansę zrobienia przedstawienia, a całą resztę muszę pominąć. I posługując się najpierw adaptacją Camusa, zaczęliśmy próbować sceny. No ale potem mnie się przypomniało, nieustannie zaglądałem do powieści, że tam są najrozmaitsze sceny, których ja nie mogę pominąć, a nie ma ich w adaptacji Camusa. Więc zacząłem powoli dodawać najrozmaitsze sceny, które moim zdaniem były konieczne. Wyrzuciłem te ściany salonu. Pomyślałem sobie, że jeżeli to jest tak jak w wierszu Puszkina, że gonią te sanie przez jakąś pustkę, no to trzeba zrobić drogę, taką błotnistą, rozjeżdżoną jako scenerię, jako scenę pokazać ją, szare niebo do tego. No i jeżeli my potrzebujemy salonu, no to trzeba wnieść te meble, które są koniecznie potrzebne, potem trzeba je wynieść.

On the one hand, I had the adaptation by Albert Camus, but he had followed the model adopted by French authors and had simply transferred everything to the drawing room; he had made it into a drawing room play. I, on the other hand, imagined that Dostoyevsky's play was somewhere where there were no walls, where everything was at some kind of crossroads, in a place where the wind was howling. A very beautiful motto for The Devils is taken from Pushkin where he describes a runaway sleigh with the horses galloping in a haze of snow and the only sound is of the voices of demons, some kind of evil spirit that's pursuing the sleigh. This was a good motto; I understood that Dostoyevsky was telling me that this was the kind of play he wanted. The Devils had been performed in Dostoyevsky's lifetime, or at least, there had been an adaptation and Dostoyevsky had written a very interesting letter to Mrs Oboleńska who had worked on this adaptation. Dostoyevsky was sceptical; he believed that theatre was separate from prose and that the one couldn't be married with the other unless far reaching changes were made in the adaptation. For me, this was an indication that I couldn't transfer The Devils to the screen, but that I had to extract from this story the things that made it possible for me to make a play, and just forget about the rest. So starting with Camus' adaptation, we began to try out scenes. But then I remembered and kept referring to the story where there were lots of different scenes that I just couldn't omit but which hadn't been included in Camus' adaptation. So I gradually began to add various scenes which in my opinion were essential. I got rid of the drawing room walls. I thought if it's like Pushkin's poem where the sleigh is being pursued through a wilderness, then we need to make a road, all muddy and rutted for the scenery, and add a grey sky. If we need a drawing room, we'll need to carry in any necessary furniture and then carry it out again.

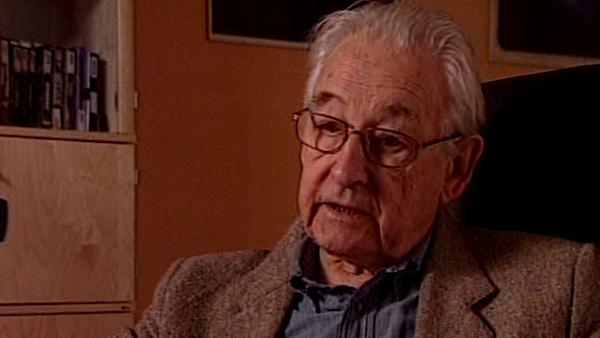

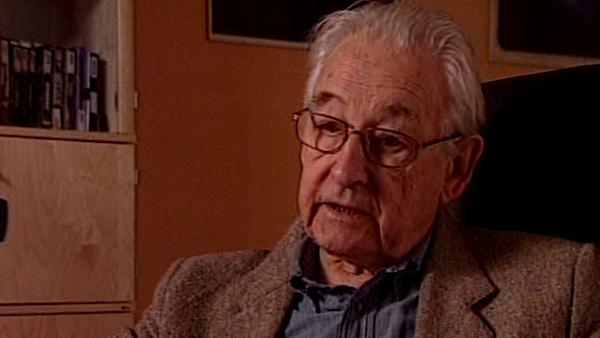

Polish film director Andrzej Wajda (1926-2016) was a towering presence in Polish cinema for six decades. His films, showing the horror of the German occupation of Poland, won awards at Cannes and established his reputation as both story-teller and commentator on Poland's turbulent history. As well as his impressive career in TV and film, he also served on the national Senate from 1989-91.

Title: Dostoyevsky's prompts

Listeners: Jacek Petrycki

Cinematographer Jacek Petrycki was born in Poznań, Poland in 1948. He has worked extensively in Poland and throughout the world. His credits include, for Agniezka Holland, Provincial Actors (1979), Europe, Europe (1990), Shot in the Heart (2001) and Julie Walking Home (2002), for Krysztof Kieslowski numerous short films including Camera Buff (1980) and No End (1985). Other credits include Journey to the Sun (1998), directed by Jesim Ustaoglu, which won the Golden Camera 300 award at the International Film Camera Festival, Shooters (2000) and The Valley (1999), both directed by Dan Reed, Unforgiving (1993) and Betrayed (1995) by Clive Gordon both of which won the BAFTA for best factual photography. Jacek Petrycki is also a teacher and a filmmaker.

Tags: The Devils, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Albert Camus, Aleksandr Pushkin

Duration: 2 minutes, 56 seconds

Date story recorded: August 2003

Date story went live: 24 January 2008