NEXT STORY

I was fortunate with funding

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

I was fortunate with funding

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 21. I’d never thought I was anything very special | 1392 | 00:49 | |

| 22. Luck in science | 1273 | 00:34 | |

| 23. Influences | 1289 | 01:41 | |

| 24. Giving advice to young scientists | 1707 | 01:23 | |

| 25. A career in science starts with an apprenticeship | 2 | 1201 | 01:45 |

| 26. I was fortunate with funding | 1059 | 02:30 | |

| 27. What makes a good collaboration? | 1139 | 02:16 | |

| 28. Theoretical vs experimental biology | 1134 | 03:26 | |

| 29. The effect of World War II on my career | 1217 | 01:11 | |

| 30. What you gossip about is what you’re interested in | 1128 | 01:02 |

That’s a natural part of the scientific career, but, you understand, in order to be accepted as an apprentice, you have to show that you’ve done well at exams and you have to give the impression that you’re, sort of, reasonably hard working and that you’re bright and all those things. And obviously, therefore, if you get taken on with a… a very good school, Harvard, Stanford, Caltech, a number of other ones of that sort, the chances are that you’ll then have… be sufficiently qualified to go… stay there, or, usually in America, go to another place where you’ll work under somebody and that is your apprenticeship. When you get… when you’re working for your doctorate, I mean, the… the so called graduate student in the scientific world is the lowest form of life, really. He’s the one… he is the apprentice. He’s like the apprentice who fills in the little bit… corner of the picture that the master allows him to do while he’s doing the interesting parts, as they did in the Renaissance and things like that, you see. So… so… and then when you’ve got your PhD, then there’s usually another year or two when you’re what’s called a post-doc, a postdoctoral. And that’s a very crucial part of your career because again you have to get… usually go somewhere else, not always, and taken on and… now you’re beginning to choose what you want to do rather than what was suggested, you see. And that’s when you begin to… to practice. Of course, some people are so good that they… they can accelerate that somewhat, but that’s the normal course, so you certainly serve an apprenticeship. It would be very difficult to do scientific research unless you did it with someone because not only a lot of little tricks and things to learn but the whole scientific attitude has be absorbed… and what you do about publication and nowadays what you have to do to want to get money, you see, which doesn’t happen automatically by any means, you have to write grant requests and so on. So, a lot of skills of that sort which you… which you have to learn.

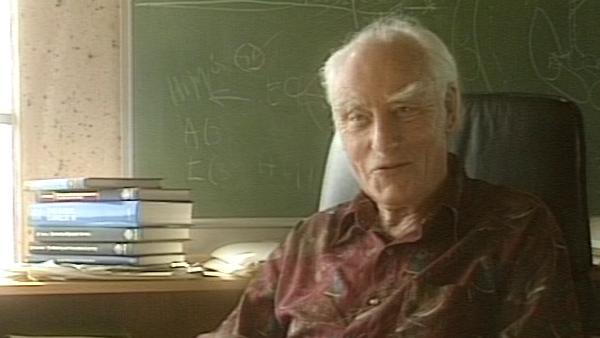

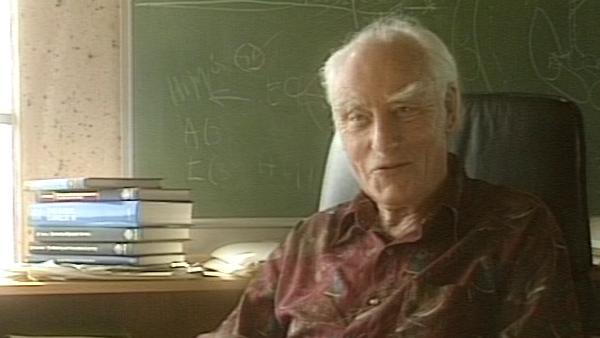

The late Francis Crick, one of Britain's most famous scientists, won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1962. He is best known for his discovery, jointly with James Watson and Maurice Wilkins, of the double helix structure of DNA, though he also made important contributions in understanding the genetic code and was exploring the basis of consciousness in the years leading up to his death in 2004.

Title: A career in science starts with an apprenticeship

Listeners: Christopher Sykes

Christopher Sykes is an independent documentary producer who has made a number of films about science and scientists for BBC TV, Channel Four, and PBS.

Tags: Harvard University, Stanford University, California Institute of Technology, United States of America, Renaissance

Duration: 1 minute, 45 seconds

Date story recorded: 1993

Date story went live: 24 January 2008